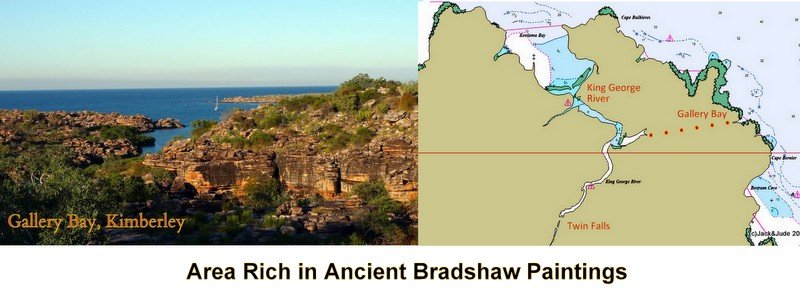

During our first visit to the Kimberley in 2007, we discovered a great love for those ancient rock paintings known as Bradshaws, which are thought to be the world’s oldest art. Our fondest memories of that voyage are treks inland searching for new Bradshaw paintings, and therefore when planning a new journey across Australia’s Top End, we pencilled in a week-long search centred on the King George River where we’d previously found a cache of great art.

Leaving our home port of Ballina in June 2013, we sailed through the wildlife rich Coral Sea, then raced past Thursday Island on strong easterlies to Darwin, logging close to 3000 miles with few touches of land.

In Darwin, a week of hectic preparations saw us crossing the Joseph Bonaparte Gulf after little rest, for we were in a hurry to begin our quest. Three days later, luck had us landfall at Gallery Bay with enough daylight to launch Little Red and search for the freshwater we’d seen on our first visit. It was vital to find freshwater there as it would be our turnaround point. But when pushing through the thorny scrub under the caves filled with rock art, Jude staggered, and then she sat down. “I feel giddy,” she laughed. “Guess I haven’t found my land legs yet.”

The very next day, hardly an hour after anchoring in front of the Twin Falls, we were climbing a steep rocky slope to gain a magnificent view over the red rock gorge with Banyandah looking minuscule amongst three multihull water beetles.

Although oppressively hot, we spent the day in training, walking several kilometres inland on the plateau above the King George River Falls, trying to adjust to the climate and terrain for the much longer walk we planned for a few days hence. Hot, sticky, our spirits sky-high, our stamina low, we found a delicious freshwater pool and swam naked without fear of salty crocs mauling us. On our way home, we dallied through the cooling landscape of red flowering eucalypts and yellow kapoks until reaching the top of the falls where lengthening shadows painted the canyons with flames of a great fire—every dark, sinister crack ending in a steel blue hearth upon which Banyandah lay, surrounded by awesome beauty.

When stepping closer to the eroded edge to take one last photo, the silence of outer space suddenly was shattered. First by a dull thud, then a cry as if a mama bear had caught a paw in a steel trap. After that, stillness returned, punctuated by the barely perceptible whimpering of Jude calling my name.

Jude recalls ~

Jack was out of sight as I stepped down off my rock ledge onto what I thought was low bush a metre below. But I just kept falling. My foot had continued into a hole until an electric shock jolted my body as I heard bone breaking, or thought I did. Stunned, a sick feeling lingered those first few seconds while I rubbed my hands that had been pricked when I tried to stop my impact against the rock.

Jack was soon standing above me, ashen faced, full of concern, bent over, picking green ants from my flesh, which I vaguely felt biting me.

Next he’s gently pulling up my trouser, examining my leg. I looked too. No signs of blood, thank goodness! Or bones sticking out. Jack carefully eased me away from the green ants now swarming over me.

The first wave of sickness having left me, I demanded the backpack he’d pulled off me and tipped all its contents out to locate the first aid kit containing painkillers, then immediately swallow four in one gulp. For support, I’m then strapping my knee tightly with a strong five-inch crepe bandage, thinking I was going to need it. Thankfully, we always carry good equipment whenever we leave Banyandah,. Loving the wild places, we’re always aware of our remoteness to help.

With the sun now only a finger width above the western ridge, what would come next figured high in both our minds. We didn’t know if my leg was broken or just terribly sprained? But we knew if we pushed the red rescue button on our PLB, our floating home at the base of the King George River Falls would be left stranded. For how would we return? Darwin lay nearly a thousand kilometres away and there are no roads. Access is only by helicopter or ship.

‘Let’s see if you can stand,’ Jack repeated louder.

‘Right,’ I nodded affirmatively, pretending to agree with him, but not really sure my leg or my will could do it. All I could think of was our Shattered Dream.

Our eyes met. I trusted him but still said, ‘I can’t do it,’ almost bursting into tears. Jack didn’t mince words. ‘Look girl, unless you want to spend the night in the open, probably making matters much worse, you’ve got to move.’ That put the fear into me. I moved, attempting to get up. Suddenly, he’s pulling me up with his hands under my armpits. Taking my weight with his shoulder, I got standing. For an instant, hope rose in me that my leg would come good. I was also thinking I must do this before the pain really kicks in.

Our first step was an awkward hobble. The second, we almost tumbled. The third brought us to the offending rock ledge where Jack sat me down. It was dead obvious the sun would soon set. And I just longed to lie down, until fear took over when Jack said, ‘Look, we’ll be out here all night unless we get our timing right. I’ll call out the steps. You put your weight on me and do your best.’

I got up, Jack supporting me. ‘Step,’ he urged, and we hobble forward. Then again, I heard ‘step’ and see him pointing to an open spot. I obey. What else could I do? I’m no wimp, and he’s puffing away with the exertion of hauling me along; anyway I was beginning to feel stupid. We’ve had our fair share of scary dramas – more than many in our life exploring Earth, and that has galvanised our partnership into a ‘we can do this’ mentality.

We navigated down into the black rock riverbed and it was much cooler now that the sun had fallen below the ridgeline. Its flat surface made going easier until confronted by bushy land rising up the other side. That bit was awkward. The enormous boulders and stouter trees stopped us going two abreast.

When we got to the descent, Jack was pretty knackered and went ahead. I tried leaning on his shoulders, but this was unsettling. I’m high above him and know if I toppled, there’d be no way I could stop falling on my injured leg.

Using my arms and one good leg, rock by rock

When we nearly toppled over, I sat down proclaiming, ‘I’m going down on my bottom.’ And surprised myself with how well it went. Yes, enormous pain, but being on my bottom low to the ground I hadn’t the added fear of falling, and using my arms and one good leg, rock by rock, some nearly my height, I practically slid down the slope. Jack fetched the dinghy to an easier place and while I waited, my left leg throbbed, feeling ready to explode.

In the last shred of light, I demanded to row us home to take my mind off the pain. Upon reaching Banyandah, we spent several minutes figuring out how to get me aboard. Which position in the dinghy was easiest to get out from? Not liking the idea of being hoisted up by a halyard, I ended up gripping the handrails and pulling my weight up with Jack’s help. Then dropped my bum on the side deck, Jack giving me a guiding shove.

Some things happen for a reason; to not lose our fresh veggies while away, we’d left the fridge cycling on and off, not our normal routine. So, good fortune found me icing down a very swollen leg and swallowing several anti-inflammatory and several more painkillers.

That night, Jack got giddy on red wine and fell asleep in the cockpit. Can’t say I blame him. I was so drugged, my brain saw me springing from bed just a tad black and blue and asking which day we’d start our big trek. Alas, reality is not so forgiving.

Jack remembers ~

In the morning, Judith couldn’t move her leg. It was yellow and blue, puffed up, skin stretched tight, her knee hugely swollen, and her ankle one great puffball. The good news was she could wiggle her toes and just move her ankle. She continued the anti-inflammatory drugs and spent the day in bed. By nightfall, she could flex her knee, so we celebrated.

After three days with little improvement, the cruise ship True North eased past to reach the falls, and I called on Channel 16 to ask if they had a doctor on board explaining Jude’s injury.

Doctor Margaret (left) most unique house call

Miraculously within thirty minutes a workboat came alongside carrying a doctor on holiday from NZ, a bright cheery lady who just happened to be an orthopaedic surgeon! After an examination in our cockpit, the doctor told us she could not rule out a fracture of the tibia or ligament damage, but she felt both were unlikely because Judith had mobility and had recovered so quickly. We then discussed our options. Considering our remote location, she said no further damage would be done if Judith continued to rest, and when the swelling went down, the doctor agreed we could sail to a location for x-rays and diagnoses. Jude, knowing the doctor came from a small country, mentioned that further treatment might be four, even six weeks away. She reassured us, “If it’s fractured, it can always be reset later.” Her visit gave us both peace of mind and the information to make an informed decision. Thank you, Margaret, and thank you True North.

Jude ~

For two long windless weeks we idled within the confines of the river, me in bed taking pills and feeling miserable while Jack edited video. Then the mechanical weather forecaster uttered those magical words, “Strengthening east winds in the north Kimberley.”

Still unable to walk, my ankle still a puff ball, my knee unable to take weight, and both of us wondering how I’d survive the jostling of Banyandah, we departed. Jack had already mastered loading the tinny and outboard alone, but wasn’t sure how he’d manage the ship without me. After clearing the islands and reefs entrapping us, we planned to keep going even if we drifted. Like Jack said, what couldn’t we do floating in a bug free ocean that we did when anchored amongst crocs and midges?

Our first day went easily for me, sitting braced in the cockpit’s corner, knee bent over a large cushion while Jack looked after our ship. We cleared all dangers before sunset, rather alarmed by two very curious humpback whales that caused adrenalin rushes by charging alongside while we were flying along with a sweet 15 knot breeze filling our sails.

Instead of changing watch at midnight, Jack didn’t nudge me awake to watch for other ships until nearly 3 AM. He was up again at first light, resetting the sails, and then made us breakfast. With only one good leg, I was next to useless in the galley when underway.

By midnight day three, we were adrift. Jack rolled in the headsail, pulled the main in tight, then put me in charge while he went below for a well-earned sleep.

Jack recalls ~

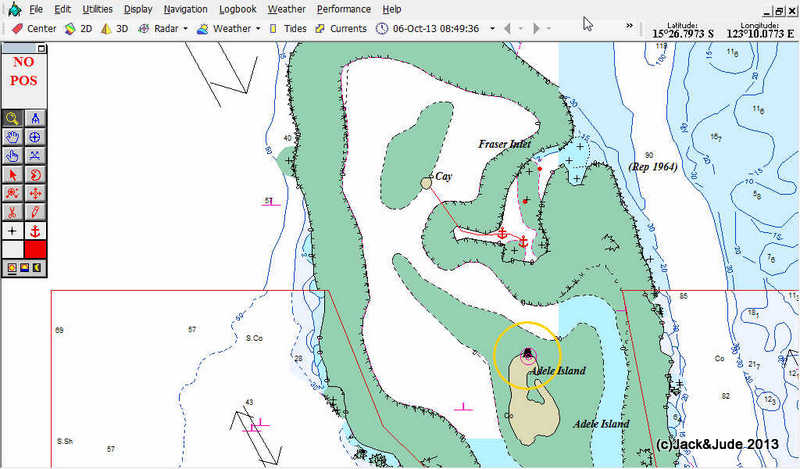

Judith looked like soggy cold toast when I arose from the aft cabin, so I sent her to bed even before surveying the calm expanse of blue sea. The bureau forecast a few windless days, so I turned to the chart, finding that Adele Reef lay a mere 20 miles further on. Our WA Cruising Guide didn’t mention Adele, forcing me to dig out our rather old Australian Pilot, which surprised me by stating that Adele had a superb anchorage which should be entered at low water. Checking the tides, we could be there just about then, so I fired up the iron topsail and off we went across the flat sea.

Adele Reef lies some 50 miles north of Cape Leveque and King Sound, and measures 6 miles by 13 miles north to south. It doesn’t have a navigable lagoon, but an inlet created where the reef nicks in several miles on its eastern side. The chart also shows a couple of sand islands, one rather sizable, with a light.

It was roasting hot by the time we arrived off Fraser Inlet, where an instrument failure caused quite a drama. Jack and I were quite ready for a rest. The Adele anchorage perfect for me. Super calm, making it easy to get around the boat. And what an amazing sight. Immense mass of sand. But which two bits were the islands? I could hardly wait to get off the boat and into the water, hoping the aqua therapy would improve my leg or just take weight off my body.

The following day, when the tide was up, we found a way through the shallows, scaring schools of fish on our way to the smaller cay. Jack ran the dinghy up its steep side, then held it steady while I crawled over the gunwale into the water. Using an axe handle for a crutch, I could only make it up the sloping sand a few metres. Dismayed, I sat down within metres of a brown-booby on an egg. While Jack went off on a walk, I talked to that bird, telling it about my woes.

I crawled over the gunwale, used an axe handle for a crutch, but could only make it up the sloping sand a few metres.

After nearly three weeks since my fall, I knew I had done serious damage. I crawled back to the water’s edge and rolled in, still feeling sorry for myself. Oh! What heavenly bliss, a weightless feeling, the water up to my chest, cooling my leg, helping the swelling. Instantly I started to feel new again, jumping along the white sand bottom on my good leg while exercising my exhausted arm muscles. Every day at Adele we repeated this. Trolling every day within minutes of leaving the cay, we always caught a fish from those teeming around us.

Leaving Adele Reef, a slow eight-day calm water sail to Dampier made it five weeks after my accident. The next morning, the Hampton Harbour Yacht Club loaned us a ute, and we drove to the Nickol Bay Hospital at Karratha. We had to wait seven hours to be seen. But fair enough. Five weeks getting to emergency meant I was at the bottom of the triage.

Unable to read the x-ray, the emergency room doctor called the visiting orthopaedic surgeon, who, by sheer good fortune, was there that day. He comes only a few times a month.

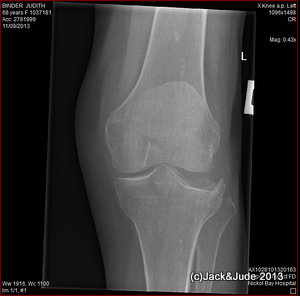

The x-ray showed that when I fell forward, the side ligaments did not snap. Instead, they held the knee together, so my femur crushed the top of my shinbone. I’m a grandmother to eight and have some osteoporosis, therefore it depressed the outside of my knee joint approximately 1cm, meaning my left leg is now unstable.

“How soon will I heal?” I asked the surgeon, and disturbed by his curt reply, I elaborated on what I do. “I go bushwalking—often. Even with the grandkids when we’re home.”

“Well. You’ll not be doing any more of that,” he told me in a stern, gruff tone. “You’ll not be able to walk on uneven ground again. Might as well give that idea up.”

Well, not all doctors get it right. Sure, the knee wobbles a bit, but there’s no pain even when tramping through the bush if I use my walking stick. Personally I like what Margaret, the NZ surgeon, recently wrote in an email: At the end of the day, if it is behaving itself reasonably and you are getting about to your satisfaction without having to limit yourself too badly, you carry on as usual.

That sounds good advice and thankfully, so far, we’re getting along very well indeed.