The Early History of Goulds Track

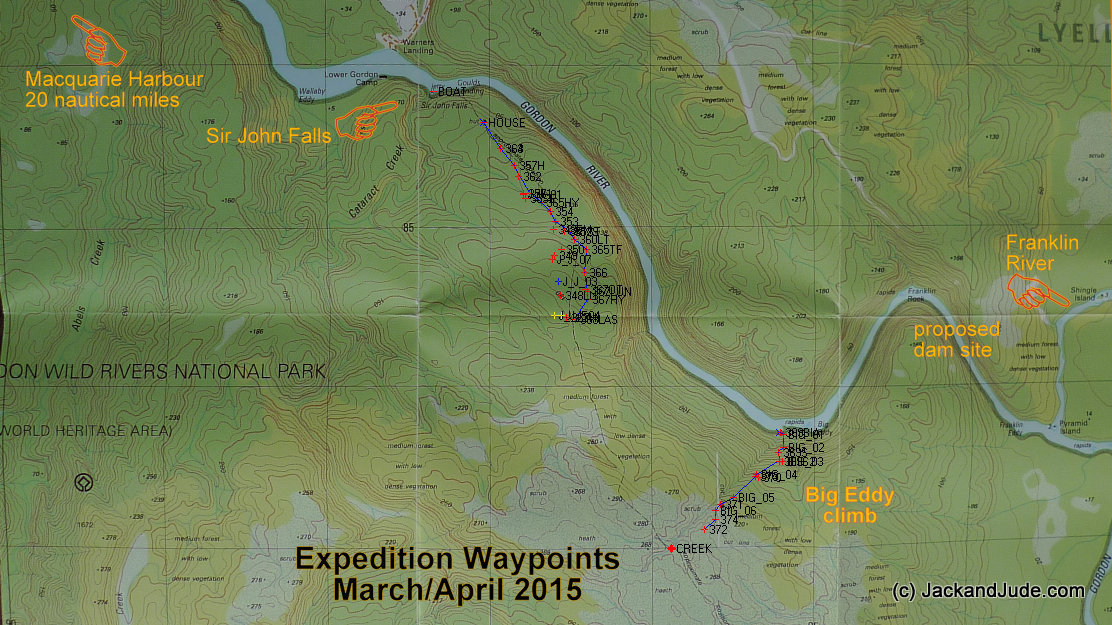

The five year exploration finding the lost Gould Track

There two routes to the track.

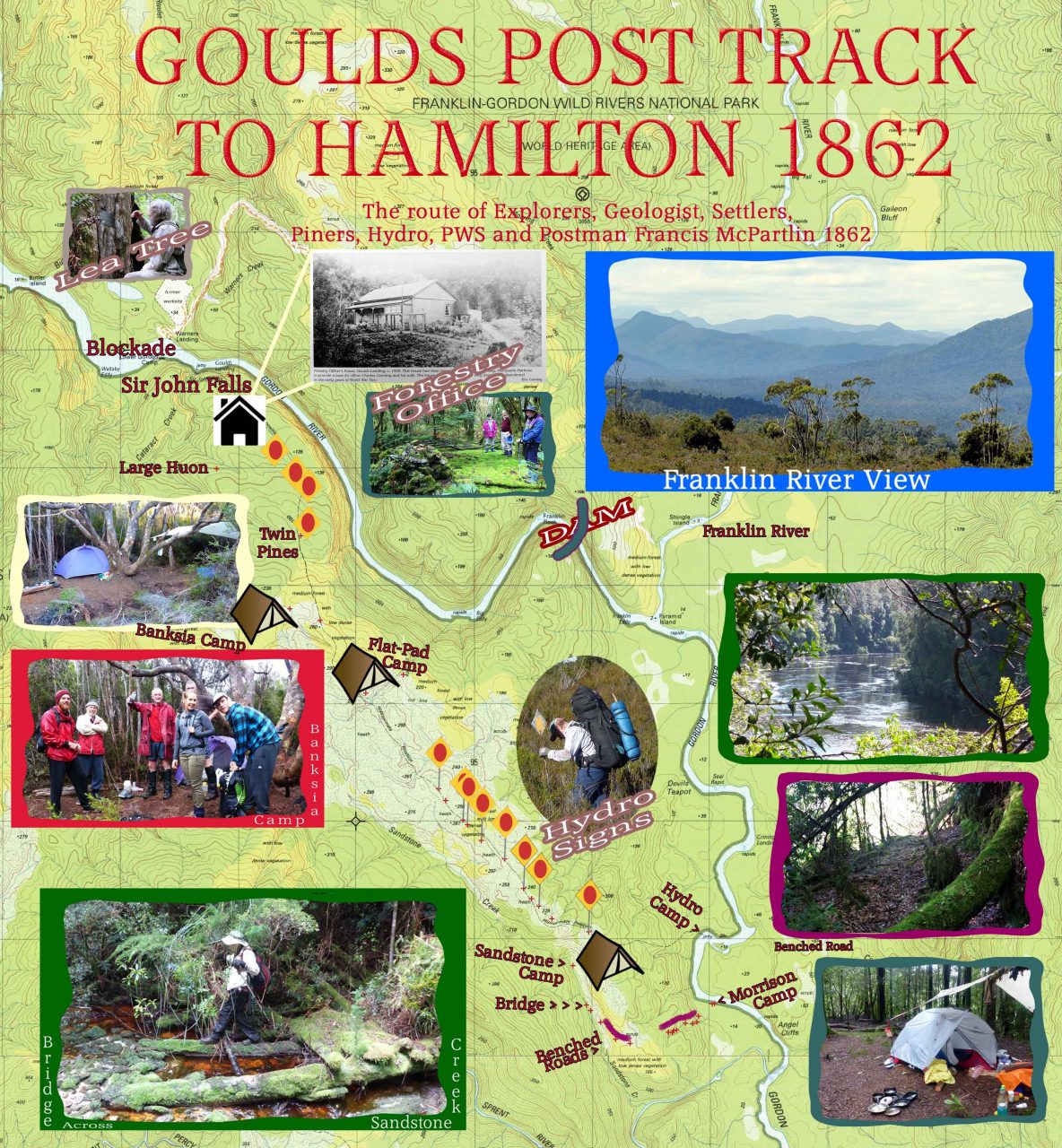

In earlier years, the jetty at Sir John Falls extended across Cataract Creek to the bank where there is an establsihed track leading around the face. You will need to use your dinghy to cross to this bank, near where a crooked tree juts up. We use that to climb up onto the track and secure our dinghy. Halfway along the path is a signpost to a track up the hillside to both waterfalls. Continuing on will take you to the old Forestry House site and there on the right of the clearing will be the start of Goulds Track marked by lots of red ribbons.

Or you can row along the shore to the first small beach where the vegatation thins, and looking closely in the water, you may spy two metal angles, the remains of the jetty. Landing there, climb zig-zag up the hill to the same opening near the forestry house. We find that way the easier. The start of the track will be on the right side (west) marked by red tapes and apparent by the divot in the earth caused by Piners Shoes on the front of their logs.

Either way, you cannot get lost if you stay in the shoe road, it’s well worn.

Heaps of baby Huon Pines, Celery Tops and other magnificent rainforest specie.

Showing some of our first expeditions to find the lost Goulds Track

Go here if interested in the five year exploration finding the lost Gould Track as far as the Rocky Sprent River some 15 kilometres upstream.

Forestry House-site Goulds Landing

Walking out along the Shoe Road to Goulds Landing

Forestry Officer’s house, Goulds Landing circa 1938

Early History of the Goulds Track

In 1859, came the first indication of a government sponsored gold search in Tasmania, hungry for much needed funding. At this time considerable interest was being showed by parties in the Circular Head district, but the way south was found to be impossible in the bauera filled ravines. The nature of the country, the absence of roads and tracks, the small size of the parties and their limited finances had combined to restrict the useful exploration that could be achieved. Only the government could provide the money and organisation for such a venture, and obtain a man with the training and ability to lead it…. The eminent geologist Sir Roderick Murchison’s choice was Charles Gould, a young geologist who had worked for the Geological Society of Great Britain. He was offered a contract by the Tasmanian Government to undertake a geological survey of the colony, which would be published in book form. Gould arrived in Hobart in August 1959, and at once went to work. (Taken from Explorers of Western Tasmania by CJ Binks)

In the first year, Gould’s team first explored areas reported as gold-bearing around Lake St Clair, the valley South Eldon, and north to Eldon Bluff to Cradle Mountain, establishing many tracks through this region. They returned to Hobart empty handed.

The second year, several disasters befell the party:

“As far as the eye could reach, it appeared to be a gently sloping plain covered with nothing but a tangled mess of Bauera. Cutting Grass and threadvines, matted together so as to be almost impenetrable… Through such country, our progress was most laborious, in wet weather almost impossible.”

Someone at the depot sent a message to Hobart that Gould was missing. Fearing a pointless and possibly dangerous rescue mission, when Gould arrived, he sloughed back through heavy rain to Linda and other members who could return to allay the fears of the Government. By the time the time the ‘rescue’ had been resolved it was well into May, the prospecting season virtually over.

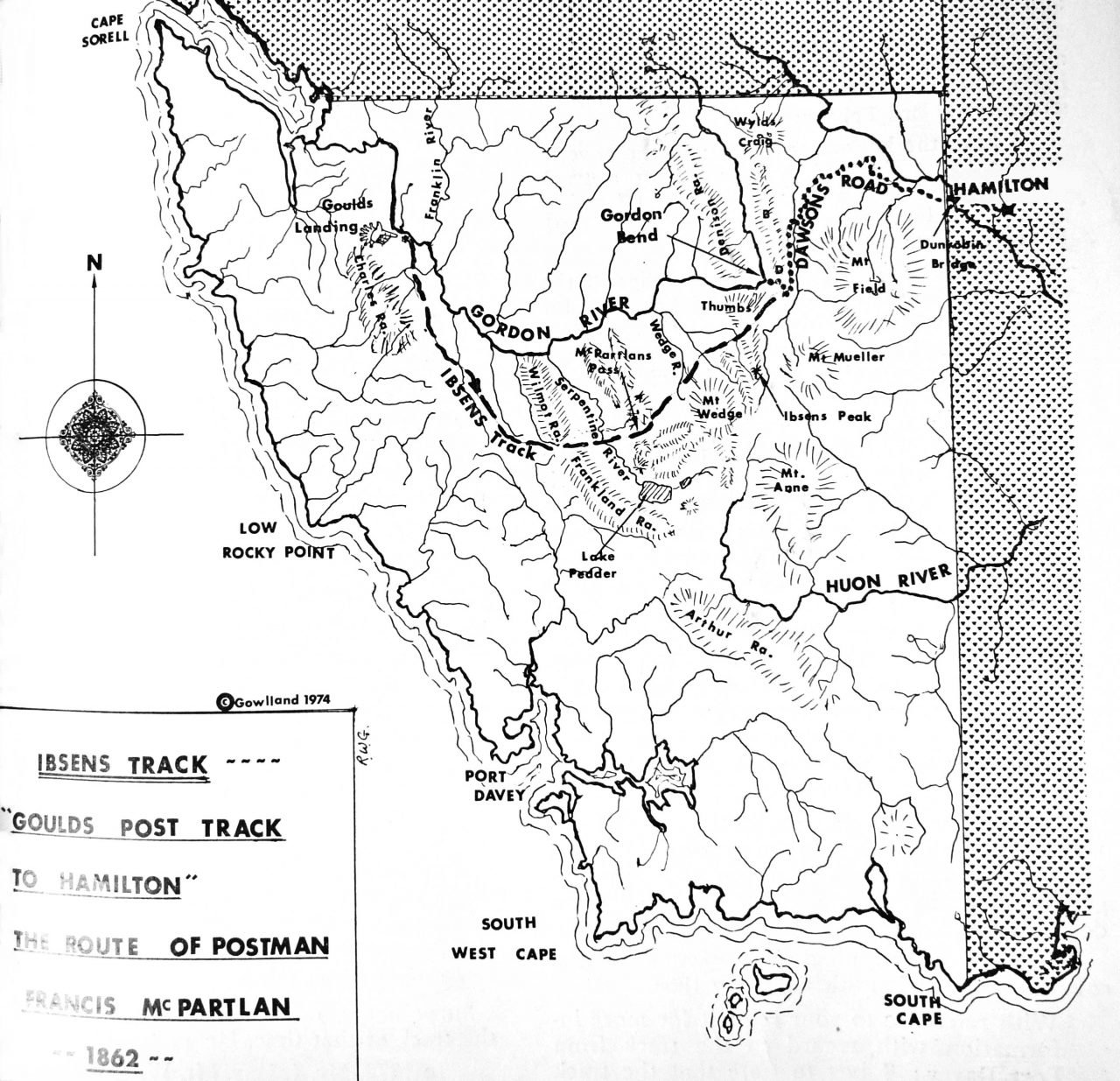

But, confident they would return in subsequent seasons, and not satisfied with the overland route from Lake St Clair, which traversed high, exposed country for much of its course, and could be cut by flooding rivers, he suggested a better route be found linking up with Dawsons Road to Hamilton from the southern shores of Macquarie Harbour. On a map he attached to his report, Gould sketched this route, as well as a proposed track from lake St Clair along the Franklin and Collingwood Valleys to the King River—which became the route of the future Lyell Highway.

The following year of 1862, he moved his party of thirty-one in two schooners to Macquarie Harbour, where he proposed to begin simultaneously tracks up the banks of the Gordon and Franklin Rivers. Gould also detached a team under Mr Ibsen to begin a track toward the Wilmot Range and the Great Bend and onwards to Hamilton.

As Ibsen proceeded up the west bank of the Gordon, he found the work tedious and spying a buttongrass plain to the south, he diverted further inland than originally intended. His final path proceeded down to the gap between the Wilmot and Frankland Ranges, across the Serpentine River to McPartlans Pass, northeast over the Wedge and Boyd Rivers to The Thumb and the Great Bend and the end of Dawson Road.

On most maps, Ibsen’s Track is called “Gould’s post track to Hamilton” because after its completion, his dispatches were sent along it by messengers. The man assigned to this job was the Irishman, Francis McPartlan, who had in 1853 returned from Macquarie Harbour to the Great Bend along a very similar route.

20th Century –

Back in 1862, Goulds Track opened the west for pioneers and prospectors when Tasmania was suffering financial hardship. That track became well used right up until the NO Dam Blockade at the “Warners Landing” Hydro worksite that drew an estimated 2,500 people. Not just Tasmanians, but also from interstate and overseas. Protesters impeded machinery and occupied sites associated with the construction work. A total of 1,217 arrests were made.

On March 5, 1983, the Australian Labor Party won the federal election with a large swing. The new Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, had vowed to stop the dam from being built, and the anti-dam vote increased Hawke’s majority. His government passed legislation blocking the dam’s construction, claiming they were fulfilling their responsibilities under an international treaty. The Tasmania Government claimed they hadn’t the Constitutional Right and took it to the High Court, which upheld Bob Hawk’s decision. After that, Goulds Track ceased to be used and the forest erased almost all signs of it ever exisiting. But it had, and it is an important part of Australian History. Therefore, as private citizens seeking a safe passge through the Southwest forests, Jack and Jude spent 5 years searching for telltale signs of this important track.

If you’d like to see more on that – go here.