We cannot change the past, but the future is within our reach.

When you last saw a shooting star ~

Did you make a wish? Or wonder what it’s like to zoom towards Earth at a zillion miles a second?

It’s something like that around here right now!

A new adventure is underway.

A new book planned.

And our website continues to reflect these wondrous events. And like a new bub, it’s alive and chucking out surprises.

Our first surprise was a pleasant one,

finding our veteran sailing craft sitting perfectly on her waterline after a Tasmanian winter, and inside, all smelling sweet and untainted.

Even better, finding our main battery bank of three truck batteries fully charged and crackling with energy. We’d left them connected to the solar panels instead of isolating each battery.

After those satisfying discoveries, we began the heavy work of removing the equipment stored below – our six-man life raft, 5 HP outboard, and sails.

Midway through that first evening, the weariness from our bus travel across the state were pushed aside to erect the awning as the heavens gifted us rain. With a dry abode, we cleared the bed. Pushing the fifty kilos of clothes and gear brought with us to the edges. Then peace, afloat.

The occasional showers the next few days provided a perfect medium for settling in and getting Banyandah’s systems operational.

After a basic sorting below decks, Jude and I re-reeved every bit of running rigging, the blocks and lines we use to work the ship that were stored below to extend their life. Awaking on Day Four to a windless dawn provided the catalyst to re-installing our massive furling headsail. Perfect also for the taxing end for end of our heavy anchor chain to help spread the wear. Meanwhile, below, cupboard by cupboard, Jude marshalled her stores, rotating up what needs using first, and updating her Excel stores list. Next task, I remounted our navigational instruments and finding them working fine, I got down to tinkering with my beloved six-cylinder Perkins Diesel. Changing the oil filter, giving the machinery a good oiling and greasing the pumps brought us to the big moment. Hooray! What a relief. First piston up fired, and away our iconic engine roared, her deep-throated rumble sounding reassuring.

Let’s Go Sailing ~

As the rain drifted eastward, we arrived home with fresh supplies from the local IGA. When stored, we raised sail to take a sweet north wind down harbour. To be afloat and sailing brought exuberant smiles again and again. Our fast speed indicating a clean bottom and the rush making us feel stronger as the miles slid past. Late in the day, Banyandah entered the Gordon River after a rather speedy twenty miles sailing wing and wing. That first night, isolated from all of humanity and surrounded by forest-clad mountains, we slept as if drifting in heaven.

Eagle Creek ~

Our Macquarie Harbour Wildcare Group looks after the track that connects the Gordon River to the Franklin via the Elliot Range. Originally cut in 1842 to transport Governor Sir John Franklin and his Lady Jane through some of the Southwest’s thickest rainforest. Beautiful to see, but easy to lose one’s way. Every year, our group attempts to clear winter tree-fall and re-tag the track, but busy schedules and Covid restrictions have seen it left for two years. So we were apprehensive about what we’d find.

To gain access to the track, one must first cross the creek’s dark, deep, cold water on a slippery fallen tree with only a hand-rope balustrade for safety. There’s a grant application in for a walkway to replace it. Wish us luck getting that.

From Eagle Creek, the next day we motored the remaining 12 miles to Sir John Falls, the furthest a vessel our size can reach. Two other yachts were tied alongside Warners Landing, the jetty established by Hydro when they were investigating a second dam across the Gordon just downstream from its confluence with the Franklin.

We took the jetty next to the falls knowing Stormbreaker was not due for two days.

Gould’s Track ~

The very next morning brought blue skies and sunshine, so Jude and I boarded Little Red for a row to Gould’s Landing, a hundred meters upstream. Gould’s Landing was the terminal for the little known, but very important track cut in 1862 by members of the Charles Gould team of geologists. That track became the mainstay for entering the west, and brought men and supplies to the then little known west coast to search for mineral wealth.

In the early 1900s, the Piners also used this established route to carry supplies and horses to their camps upstream on the Gordon, Sprent, Lawn, and Denison. Then in the 1960s, the Hydro-Electric Commission (HEC) used the Goulds Track when surveying for the Gordon below Franklin Dam.

All of this activity ended in 1983.

Blockade ~

The Hydro-Electric Commission had begun building infrastructure for a second dam when, in mid-December 1982, six thousand Australians blockaded the HEC site at Sir John Falls. Over the next three months, there were 1,272 arrests. Following the ALP’s federal election win on 5 March 1983, the new parliament passed legislation to protect Tasmania’s south-west. The blockade earned a most conspicuous place in the folklore of Australian environmentalism, and soon after, the declared World Heritage land became a closed area.

Photo by Jerry De Gryse. Welcome Party on Arrival at Upper River Camp via the Boat J-Lee-M, 1983

nla.cat-vn6978126

From 1983 until 2015

Nature took back what had been a ribbon of access to one of the world’s most exquisite forests. Originally a cart-width across, hardly a blip to the natural world, lost to adventurers, nature lovers, school children and folk like Jack and Jude who love Earth more than all else.

The story of our years pushing through snarls of bauera, bruising shins on horizontal, cutting hands and arms on razor grass, reaped its reward two years ago when we connected all of our GPS dots to the Morrison Camp, near the Rocky Sprent. In a fun project full of compensations for the few comforts, we found and tagged nearly twenty kilometres of the historic Gould’s Track that ran within thick forests and across exposed button grass plains.

On large screens – press play, then use the sprocket for 720P & expand to full screen

More photos – Hunt for Huon Piner Remnants ~ Gordon River

Holiday ~

It took a couple of days to clear the fallen limbs and re-tagged where necessary, then we sauntered back downstream, After a few lazy days admiring the river’s isolated splendor, we found ourselves in spacious Betsys Bay, with the call of the west coast just over the rising hill in front of us. Amazingly, the sunshine continued. So we planned a hike across the four kilometre finger of bushland to the wild west coast.

Sloop Rocks West Coast ~

Imagine a coastline without even a hint of humanity. As created. Blue ocean waves, brilliant buff sands, outrageous rock formations, and an unlimited horizon that invites dreaming of the faraway.

We cleared intruding branches from the Betsy Bay track and renewed lost tags so that those following us will not get lost going to this most inspiring vista where energy flows into our spirits. Where the worry and concerns of human life evaporate into the blue never-never – begging the question, is humanity missing the real point of life?

After three hours of toil along the track, we took rock seats to satisfy our hunger and discovered to our dismay a bloated dead whale. Its fixed grin of death shocked our sensibilities. What an enormous creature! Now inert, life gone, we felt pity. Why? Where? Flashed through our thoughts until we remembered the massive pod of pilot whales that were lured into Macquarie Harbour a few months earlier. Many stranded on its shoals. Four hundred and twenty of nature’s finest creatures lost their lives in that terrible incident. And here was one, probably one towed from the harbour after dying on its shores.

Minutes later, and only metres along the beach, we discovered another bloated dead creature. Then another, and another. Along a short stretch of beach lay eleven of these magnificent, unfortunate creatures with smiling grins of death.

On large screens – press play, then use the sprocket for 720P & expand to full screen

Isolated from all humanity, no internet, no phone, only the roar of surf and squealing of seabirds heard upon the crisp, saltyness of the faraway. There we encountered a most amazing sight. Not the whales. Beyond them was a sandhill twinkling as if diamonds lay scattered upon it – sparking a memory of Stephens Beach in Port Davey. The Needwonnee midden. With that, we saw where a clan of Toogee had lived in a quiet corner of heaven. The blue ocean before them, bones of beasts like seals and whales scattered amongst the pot-pourri of seashells recorded decades, maybe centuries of life close to Nature.

With racing hearts, we worked along the side of the sandhill until breasting its summit, and there we came upon the most amazing sight of three freshwater lakes of the darkest blue. Amazement sent our heads imagining ancient ancestors living in harmony here. I turned about, the blue sea spread to a sharp horizon ignited in sunlight that led to the sand slope carpeted with long-ago feasts. What a most perfect place to raise a family. Plenty of fresh air, adventure, and action. Reminded me of rising my two sons within Nature’s arms.

Our Newest Addition ~

Not a new bub, but just as pretty is our toothbrush holder fashioned from the root of an ancient Huon Pine.

Jack and Jude live fortunate lives. We keep it simple and work hard. We are frugal. We make what we can and learn how to create what we need. Time is precious. We waste little—even when drifting across the seas – when there’s a freedom few know, we invite our imaginations to run wild.

Want to live like that? Be brave. Be daring. And be smart. Take command of your life. First Command: Take care of your body. It contains the strength and spirit. You won’t do this when you’re feeble.

Sail for King Island ~

With a ship in good trim and well stored, our spirits lust for the freedom of the open sea. And we start looking for a weather window. Let’s see – First, to sail for King Island. Covid will dictate our course from there.

Modern weather forecasting makes voyage planning much easier than the days of tapping a barometer and looking skyward. On the internet, we saw the week ahead would bring warm windless sunshine before a cooler southerly change brought good sailing conditions. Great! What could be better than a few days paddle up the King River to a camp under the stars just downstream of Teepookana, the place where construction of the railway first began.

Until next time, Wishing you fair winds. J&J

Flying High at George Town

Published 2 February 2021

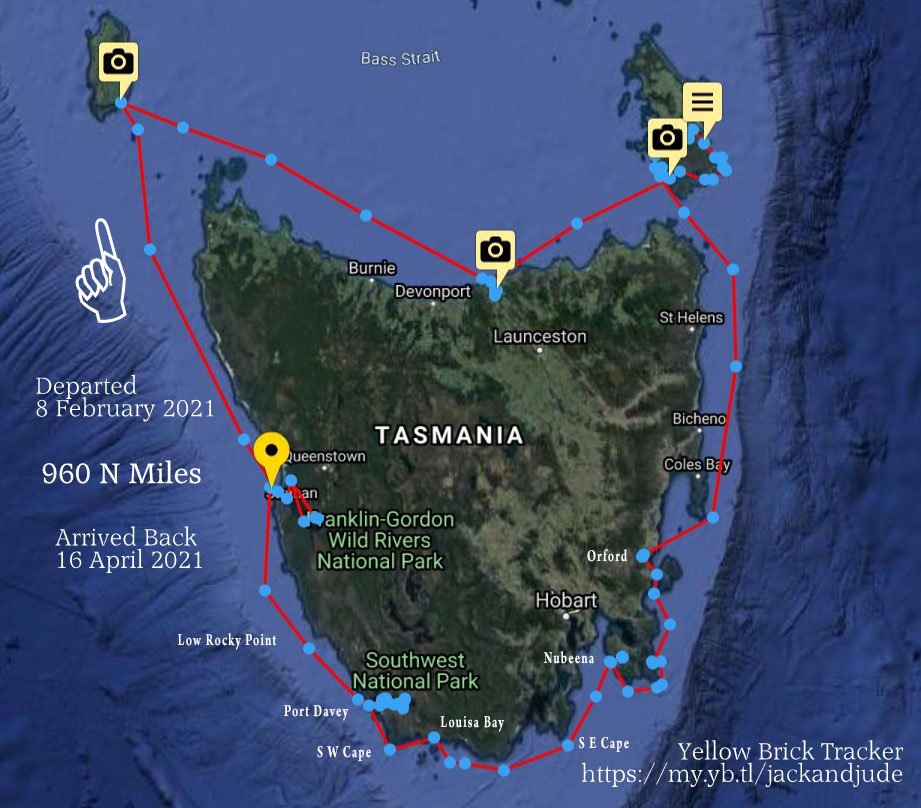

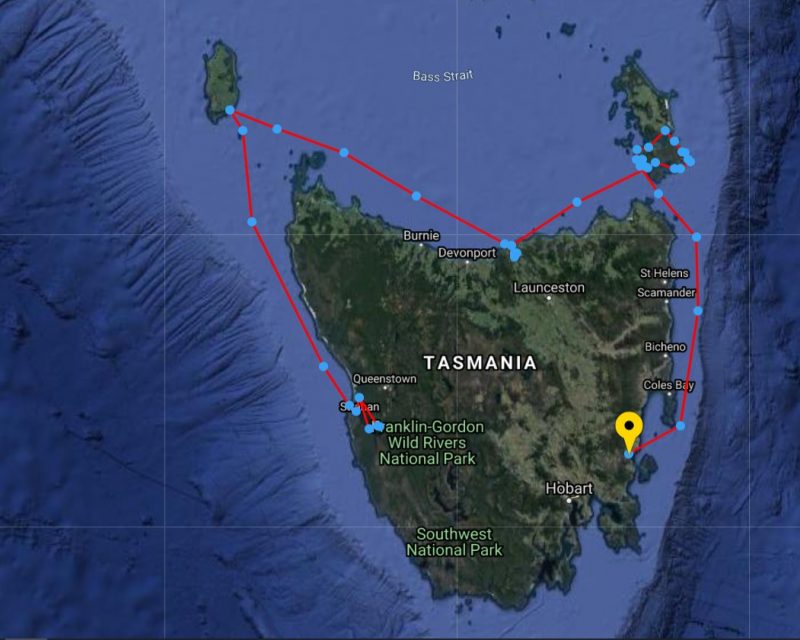

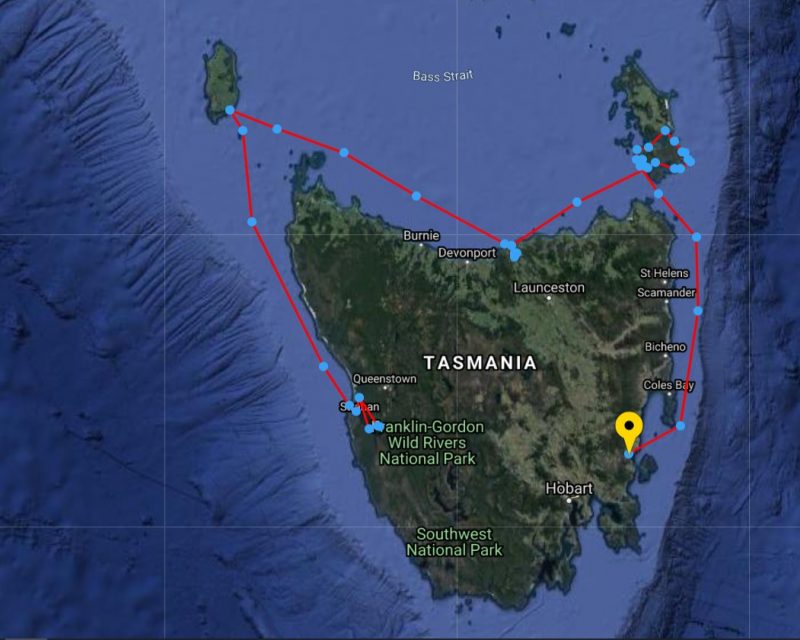

Plenty of Sea Miles since last report ~

Starting with a fast overnight voyage from Strahan to Grassy Harbour on King Island, dodging shoals off Tasmania’s northwest tip as the Southern Cross drew overhead, and then passing east of Reid Rocks to take advantage of the forecast morning shift of wind to sail straight into Omgah Pass under full sail. Once on the island, we enjoyed a few marvellous days with dear friends and enjoyed one heck of a dinner party.

King Island ~

On King, we’re never bored. Strong Easterlies in the harbour make for a stiff row ashore and being able to borrow a car we enjoyed a sumptuous visual treat on the other side of the island.

From atop the sheer cliffs at Seal Rocks, before miles of blue Bass Strait, watching the spume of white capped waves crash and spray onto jagged rocky shores, our thoughts wandered to the yin and yang of life.

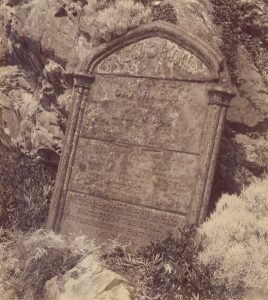

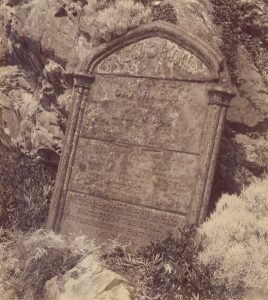

Seal Rocks

Stone tablet for those who perished.

Many lives perished on windy nights at King Island. Just a little up the coast from Seal Rocks is the monument to the four-hundred who lost their last breath on the last night of their four-month voyage to the promised land. A horrendous winter night on board the Cataraqui in August 1845, tragedy struck at the ungodly hour of 0430. Australia’s deadliest maritime civil disaster, for it was not simply drowning, but being cruelly dashed against jagged rocks on foaming waves between the vessel and shore.

Well more than a century later, in August 1978, Jack and Jude came to know winter and Bass Strait on a voyage from Albany to Eden with our two little sons on board the Banyandah. A half mile wide trough between fifty footers, the tops roaring white like the Pipeline at its wildest.

Here’s the only clip of the Four J’s in action back then.

Grassy Harbour – Photo by Lyn

Too Many Easterlies ~

Zoom, away early, driven by a tailwind, bound for Three Hummock Island forty miles across a strait, which we passed around dinnertime. And kept right on sailing under a starry night, finding calmer waters off Tasmania’s north coast. First glimpse of sunlight flowed down upon the towering knob of Low Heads directly ahead. Sailing for the fun and challenge, we savoured the simple pleasure of managing our craft with nature’s forces to have our anchor down in the quiet waters off Kelso by 0900.

Wanting peace for a few days to complete an assignment best created in the solitude of Banyandah drifting in a lonely anchorage. On this coming Monday, the lovely folks at the George Town Yacht Club will let us hire their pontoon to do some much needed boat maintenance.

Who has done this ~

Raise your hand if you’ve ever painted a 15 m tall mast while swinging on a thread from the masthead. Jack did, at 76 years young. Pretty good, hey? Not once up and down. But five times! Two to three hours aloft each stint. Clean and prepare, then anti-corrosion primed where needed. Then an enamel primer followed by two coats of gloss enamel.

Ours is something like this.

We had a stupendously good routine. Jack wore his night-watch harness and sat in our padded bosun’s chair strung from the main halyard, which he modified by adding an extra block as a backup in case the main one shattered. Once rigged, and dressed in long sleeves and trousers, he climbed the mast using the steps that go to the masthead, while I took up the slack.

We communicated every movement back and forth to confirm the readiness of releasing, and lowering, and securing the line. When re-securing his safety line, usually from one step to another, Jack took his weight and clung to a shroud, a spreader, or a step. Once secure, he could work confidently. But he found it a tiring ordeal, using his legs to hold him in position while cleaning and painting. Poor Jack. Not a kid anymore. He felt much better after an hour stretched out like a zombie.

Anyway, the job’s done. Looks smashing. Should protect our spar for as long as our log keeps recording adventures.

Next stop – Furneaux Group ~

We’re on our way to the Furneaux Group, with a flexible plan. Re-visit the Sydney Cove resting spot at Preservation Island yet again. It’s a fabulous walk across impressive granite-tor country to a spectacular historical location. Watch our YouTube video and you’ll know why we drop in whenever in the neighbourhood. We’re also looking forward to some yummy flathead fish dinners, so we might pop into Jamieson Bay at the far southeast corner of Cape Barren Island. That’s where the gods make wind by dancing atop mount Kerford, so the locals tell us. In March 1773, it was Tobias Furneaux in HMS Adventure that named the south-eastern point of the island “Cape Barren”.

Explore the Unexplored ~

Other than that, we might poke our bow into a few unexplored bays and chance crossing the Pot Boil shoals to enter Lady Barron in a quiet spell. Who knows, the Harbour Master might have a mooring we can borrow so we can go walkabout on Flinders Island. Maybe climb Strezleki again.

Until next time – stay safe – and together, we’ll beat this pandemic.

J&J

Plenty of miles under the keel with more tough ones ahead.

Furneaux Fast and Furious

Nubeena, 20 March

Happy Birthday Wendy and Barry ~

There’s a big bash at their place in Nubeena tomorrow, and we’re looking forward to sharing good times with friends. But, we’ll have to keep ourselves in check because it looks like we’re going back to sea early the following morning. The weather dictates our movements around this island, and for a limited time, a whopping big HIGH is generating heaps of northerly winds and beautiful sailing.

Furneaux Group ~

Ending our last blog, we had given our mast three well-needed licks of enamel in the Tamar, finishing just as a handy westerly breeze ruffled Bass Strait. We gave that final coat a day to harden before hoisting sail late the following afternoon to voyaged overnight to the Furneaux Group of islands. There to meet with new friends John and Geraldine, first met while clearing the Goulds Track after they had followed our pink ribbons from Sir John Falls, twenty miles up the remote Gordon River on Tasmania’s west coast.

John and Geraldine on Goulds Track

Leaving the Tamar River, our course took us east to one of our favourite spots, Preservation Island, in the shadow of Cape Barren Island, with the wreck of the Sydney Cove, beached there in 1797. These Bass Strait Islands are challenging because there are no all-weather anchorages. Adding to this, troublesome ribbon grass grows thick just about everywhere causing havoc for anchors. Plus, gales a plenty. The NW wind filling our sails, the harbinger of the next one.

Gale Number One ~

Not only is Preservation dominated by impressive granite tors, the sand patches at Hamilton Roads are handy places to hang out a westerly gale. Our first striking the day after arriving. A day and evening of screeching winds blew through, then we awoke to a day of total bliss. Overhead, a perfect bowl of washed blue containing crystal-clear air made every view a masterpiece of supreme scenery. We packed a lunch, then launched Little Red to go walkabout and revisit historic spots. The lookout of circular stones built by marooned sailors commands a view over Armstrong Channel, its isolated beauty in every shade of blue finding containment within granite and sandstone. Below the lookout, up against four gigantic wheat coloured tors, the survivors built a camp from salvaged sails, where archaeological remains were unearthed. These historical remnants are on display at the Queen Victoria Museum in Launceston. Well worth a visit, or if unable, peruse Michael Nash’s well-illustrated book, “Sydney Cove.”

Easily tramping through waist high undergrowth, we next came to the waterhole dug in 1797 on this otherwise waterless island. Recent rainfall must have been scant, as this was the first time we’ve seen the waterhole dry.

From that clearing, over a slight rise passing between two gigantic granite outcrops splashed with orange lichen, we came to the magnificent Store Beach, named for the stores landed there during the days after the ship’s grounding. The sand is a lovely beige running to pure white above the tide line. Blemish free as if the Creator had just completed it by adding a pair of decorative mini-tors, one with a balancing stone atop that adds further wonder, watching to see if it moves in the gusts.

From this vantage point, the final resting place of the Indian built Sydney Cove can be seen next to a rock that pops up close to the smaller island, named Rum Island by historians as it kept the many gallons of salvaged spirit away from desperate sailors. A splash of translucent Caribbean blue separate the two, making the view a picture-perfect postcard.

Those wanting to read the whole fascinating story of this historical event that also includes the first overland walk by white folks on Terra Australis, best find a copy of “The Wreck of the Sydney Cove” by Max Jeffreys.

Gale Number Two ~

A light breeze introduced its coming; prompting us to shift a few miles further into Armstrong Channel to behind Wombat Point and the south side of Cape Barren Island. We’d been there once before and remembered a windy night and dragging anchor and not exploring its hinterland. Our topographical map shows a shallow lagoon just a few hundred metres inland, which tickles our curiosity. So, with an afternoon and night before the serious winds, through skinny water we dodged a bump until anchoring a few hundred metres off a spot on the sandy shores where I thought I detected a track on Google Earth. Then we launched Little Red for a light upper body workout rowing in.

Cape Barren is an Aboriginal Island whose cultural centre is a tiny pocket on the north shore, called The Corner. In 2016, the island’s population numbered 66. There are few roads, and many 4WD tracks, mainly to fishing spots. Wombat Point Bay showed one thin line leading to The Corner, but we saw no signs of habitation on shore, just seagulls and us.

Landing and pushing through shore scrub, we stumbled upon a disused track and followed best we could, until breasting a rise we beheld an impressive kilometre long dry pan that held small pockets of reedy water at its eastern end with several pairs of ducks. Lining the shoreline, squawking plovers were hosting a gala jamboree, courting the young pretty ones.

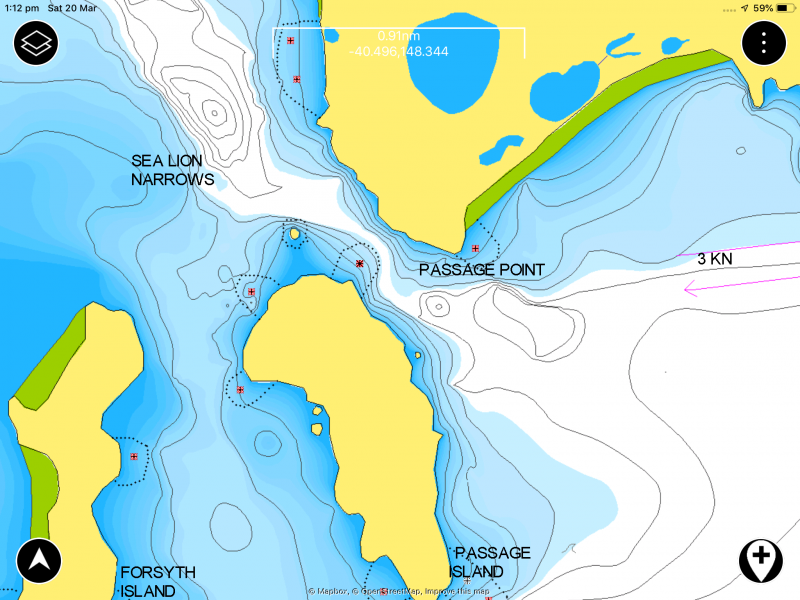

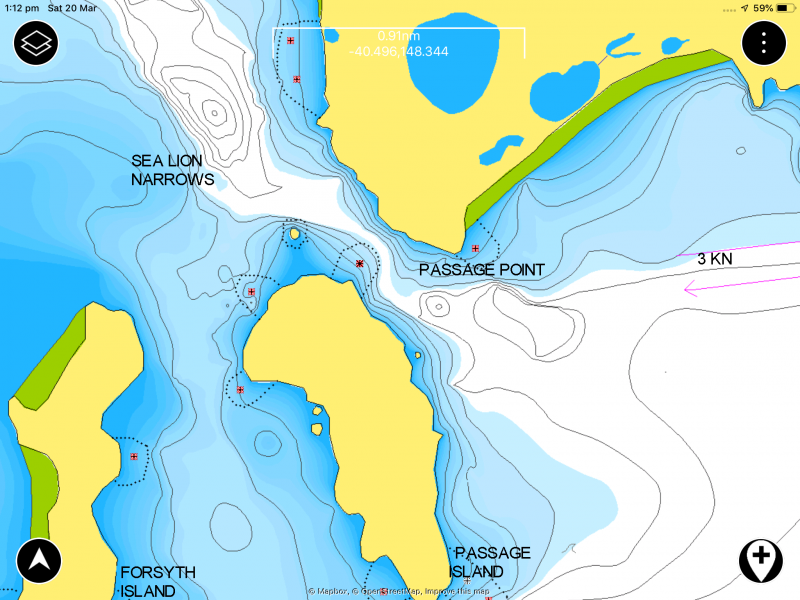

Sea Lion Narrows ~

A silent cold night under a star-filled sky brought dawn’s northwest winds churning up Armstrong Passage. Needing better shelter, we scurried downwind under sail with gathering storm clouds pursuing us towards Burgess Bay, a safe anchorage on the east coast. Between us and that protection stood the much-feared and respected Sea Lion Narrows, where swift currents stand water vertical.

Sea Lion Narrows

The narrow passage between islands is further encumbered by a rock midstream at the tip of a sandspit.

We’ve been through both ways. The first time, a nasty blow, seeking shelter, frightening seas, and the second experience the exact opposite. The current with us, on a light silent zephyr we glided through as if ghosts. Feeling the experts this time, all the elements with us, we held full sail and filmed the adventure. So quick, doubled our speed. Got exciting, land so close, passing swiftly, alter course into impressive whorls and overfalls that Banyandah slipped through, a veteran voyager in the hands of an accomplished lady. Bang, suddenly it got busier. Past the point, the wind increased just when we needed to alter course and take the wind on our beam ends. Sails had to be tightened. Winches cranked. Sheets heaved and secured. Jude steering to the next headland, sails nicely set and we’re flying along. Fun!

Burgess Bay ~

Burgess Bay should have been a top spot to weather a storm. But, unfortunately, it sits under an old nemesis of ours, Mount Kerford, atop which the locals claim the wind gods dance.

Against blasts flattening my curls, we climbed closer to the shore seeking shelter after safely negotiating Gull Island Pass, the final hurdle into Burgess Bay. The gently shelving sand bottom allowed us to anchor close. After tidying up, when shipshape, ready to go, a cold beer in hand, we fished, thinking there had to be a few flathead about. No luck there, and no luck with the weather.

As darkness closed in, blasts down the mountain sides found new fury. At its highest, forty-six knots of pure natural power screeched down Mount Kerford, causing groans in our ground tackle and thoughts of snapped anchor shackles. So, Instead of reading or watching a video, with so much noise, we glued our eyes to the GPS ship blinking .03NM from our anchor, (that’s the length of our anchor chain) and like always, we talked about what we’ll do when this one blows through.

Gale Two started to ease at a respectable hour, allowing us to set an anchor alarm and settled into our fore and aft sleeping positions. We dozed. And like other creatures dependent on self-survival, an inner-self monotored the severity.

We were now on the east coast of Cape Barren, with the island between us and the forecast westerly winds – perfect. The sea should be calm, so we laid out a tour of anchorages following the weather. The first, just five miles up the coast at Thirsty Lagoon.

The East Coast Of Cape Barren Island includes eight valuable Ramsar accredited wetlands. Its remoteness means that it is a largely natural system and is in near natural condition compared to other coastal wetlands. Most other extensive wetland ecosystems in Tasmania have been the subject of significant decline and large areas have been lost and most others have suffered significant alteration in some way. This naturalness makes it unique within Tasmania and the South Eastern seaboard of Australia.

Visions of launching the Green Machine kayak for a leisurely paddle upon its huge enclosed waters saw us raise sail for a fast morning passage along the sandy coast. Ahead, runs of long swell formed columns of white soldiers marching across the rocks off Harley Point. Reaching the apex, we gybed sails and changed course towards a beaut little cove. Long sandy beach, nothing manmade, But the tide barred the lagoon at its midpoint.

The same long gentle roll rounding Harley’s Point brought a comfortable night, during we learned of a new gale in the evening forecast. Our third gale this week.

Next morning – gorgeous, a 100% world of Nature, most of it reflective calm, but there were hot spots of surf and breakers. We launched the Green Machine kayak for a look at the lagoon entry, but thought better of challenging the surf. Instead, beaut morning, lovely seascape, we paddled towards Harley Point and glided through the shallows to a quiet landing spot that invited us to beachcomb while the tide rose.

While strolling the lonely strands, a cray-boat came in. So, while on our way to the lagoon entrance, we stopped by and met Tony and his deckie Marvin. Tis a small world. We had met Tony’s brother years earlier when we’d shared an anchorage up the coast at Babel Island. For an hour, drifting alongside we exchanged news and views, and asked his advice on the coming storm, Tony suggested the next bay along. And with that, we shoved off to brave the small surf into the lagoon.

Oops, Got so carried away timing our surf ride in that we forgot about the speed of the incoming tide filling the lagoon and had to paddle like Olympians to get out again.

Gale Number Three ~

Maybe we were getting hardened to the noisy wind throwing us about because after shifting to the anchorage Tony recommended, we managed easily. Lying in bed, the anchor alarm set, watching a movie with the sound turned up high.

Farsund ~

In 1912, Captain A.E. Abrahamsen of the Farsund, a three masted steel-hulled barque of 1,351 tons, made the fatal mistake of running aground on the worst sandbanks in the Bass Strait Islands. Separating Cape Barren Island from the larger main island of Flinders is a wide channel named Franklin Sound. Its eastern entrance has the descriptive name of Pot Boil. Fast currents run through shifting sandbanks that reach up to six miles offshore. We have been through them a few times, and have a few grey hairs to show for the drama. But Captain A.E. Abrahamsen of the Farsund must not have known about them. The rusting steel hulk, home to hundreds of smelly cormorants, and has lain in shallow water for over a hundred years.

During the calm following our third gale, we decide to pay her a visit.

Getting to within paddling distance in the Banyandah was scary even with modern navigation gear, but with care and patience, we found a spot a half mile away in five metres of depth. The tide rushed past going north towards the Farsund. The outward journey went okay except for a few surprise breakers over shoals that put us on high alert. But we made it without getting too wet. When close up, Jude shot some awesome footage while I used the paddles to kept us from joining the seabirds squawking along the deck.

When a wild one swept through, we thought why push our luck, and started for home. Paddling up wind and against the current, an odd seventh swell would sweep through, keeping us focussed and alert. The Creator must smile on fools like us, because we got back without swamping the Green Machine. Here’s a video of the action.

Extraction ~

But then came an even more daunting task. We could go seaward around the shoals then north to the entrance to Pot Boil and brave its overfalls again. But, there’s also a channel inshore along Vansittart Island. To reach it meant dodging a maze of sand spits that break in high spots. We’d gone through it from the north years ago, and found this end really scary. And we failed from this end a couple years ago and had to turn back. But, good fortune shown upon us because Tony had kindly given us a few of his waypoints, and after entering them into our chart plotter, we set off with fast beating hearts.

We planned the entire operation around the wind and tide. We had sailed to the Farsund at the beginning of the rising tide and from there we carried on with the flood adding more depth and more speed to our craft. Perfect as clockwork, nary a fright just awesome following Tony’s track in deep water between breakers then quite close to reddish sandy stone Vansittart Island. With the last of the rising tide, Banyandah popped out a gap into the main channel leading into the small port of Lady Barron. Where we took up a MAST mooring in time for beer o’clock after a remarkable day.

Lady Barron ~

There must be trouble in the fishing industry because we didn’t see any fishing boats and heard there are none around. Instead of them lining the jetty, a ghost ship hung there with tattered sails fluttering in the afternoon breeze. The story, from the Harbour Master, it seems a lone sailor set off from Eden, and no one heard from him again.

A long weekend holiday created a deserted town, so we strolled alone the few empty streets, had a coffee at the only store, then enjoyed what every sailor loves, a hot shower with plenty of freshwater, compliments of the community. With good phone coverage, we spoke with the family for hours, told them our stories, sent off heaps of photos, washed some clothes then enjoyed another hot shower.

Unfortunately, the meteorologist forecast another blow for mid-week. Lady Barron is not to our liking during strong west winds, so I got keen to check out a couple of new anchorages that looked promising. This proved to be a mistake!

Travelling west through Franklin Sound, tide assisted late in the day, the westerly winds arrived early. The first anchorage didn’t appeal forcing us to power against the wind to reach Munro Bay, the second option in a magnificent setting on the north side of Cape Barren Island. Across Franklin Sound dotted with islands, the jagged Strzelecki Peaks erupted from Flinders Island. While nearer to us, Devils Peak, a bald rock, and Double Mountain kept us company.

Some storms begin easy. All night a gentle breeze held us pointing steady to the shore, and we relaxed, thinking our Manson Boss had pierced the thick ribbon grass carpeting the bay. When morning’s grey light brought the heavy guns, lying in bed, Banyandah sheared off, and both of us held our breath until she pulled back in line with the wind. We had company in this bay, a yacht anchored in the prime position. Over the next half-hour, the gusts got more savage until we noticed the other yacht dragging. When a boat falls off the wind in a gust and never pulls back straight to its anchor, she’s dragging her anchor. In this case, through Ribbon Grass gathering a crop of weedy ribbon, hundreds of them. They generally clog an anchor. We watched the vessel drag abeam of us with no one on deck and gave them a loud shout. Up popped a man, who immediately ducked below to reappear with a lady, both in wind cheaters. While we sat comfy in the lee of our dodger, they started engines, but, instead of resetting their anchor, they motored off toward Lady Barron, leaving us alone in strengthening wind gusts.

Munro Bay, Franklin Sound

Munro Bay is not what we’d class a storm anchorage. Beautiful views, with inviting rock outcrops to explore by kayak, but it’s very shallow for a long way out and full of ribbon grass. As the day progressed, so did the storm. Bigger blasts created bigger seas, but we held–until after lunch. When, after a savage blast, Banyandah did not pull back straight, but stayed heeled over. The wind on her side. Not quite battle stations! With nothing behind us, at first we just watched her drag, hoping the BOSS would get a grip of something. But it didn’t. The further out from shore we blew, the bigger the sea, and the faster we dragged. After an hour I decided to reset. Now, re-setting an anchor in 30 knots of wind is far more difficult than in a breeze. Just getting the head of the ship up into the wind takes heaps of power, demanding excellent helming and coordination between the anchor man and helmsperson. Voice commands are blown away, so we use hand signals. We have our own. I point where to go above my head so Judith can see. Go faster is a hand motion forward. Slow down – open hand patting down. Anchor off the bottom—finger up. Anchor in the rollers—thumb up. A few we use. Windy black nights are worse.

We got back to our original spot and thought we’d try closer in and get some protection from the rocks off the point. At minimum depth, the moment Jude took the revs off the engine, we sheared off and the anchor went down. No stopping now. I let out chain until most of it was out then let the winch take some strain before releasing more, hoping to dig the anchor in without ripping it out. Ribbon grass is the hardest to penetrate. Its roots are thick and interwoven; its strands are long flat tough stuff that clings. At extreme scope, we held for a minute or two with the chain streched flat, giving us hope, then blast, we were off again.

Retrieving our anchor, we then tried on the other side of a shallow area to see if we could get in a better spot. But ended up uncomfortably close to rocks behind us that we’d hit if the anchor let go. So we held a brief conference. Jude suggested going further out into deeper water where ribbon grass may not grow. The seas would be bigger, but if we could find a sand bottom, the bigger seas wouldn’t matter to the BOSS. So we drifted downwind into around 15 metres of water and did our thing of setting our anchor in blustery, rocky-rolly conditions.

Now this might sound strange, but anchoring in deeper water has advantages. Imagine the weight of all that chain sloping down, acting as a buffer. The catenary smooths out the jerk from windblasts. In shallow water, the chain lies on the bottom and the pull is direct. Here in deeper water, it worked magnificently. Although the wind swell was more powerful, we held bow straight into them. With the anchor in sand; she held through the deterorating conditions we faced later that evening.

But we’d had our fill of gritting our teeth and hanging on. Next morning, in calm conditions with just a light north breeze, we sailed south around the corner to Thunder and Lightning Bay, where we’d get ready to depart the Furneaux Islands.

Passage South ~

While in port, we had watched several systems come and go, and now saw a narrow opportunity to sail south, not just another island hop, but a long way down Tasmania’s East Coast. An obstacle we had to consider is Banks Strait. It’s unwise to buck its fast currents, or wind against tide that sets up horrible seas, making life miserable. An early start would be required. That left time for a walk on the shore to explore Key Island Bay and see again the iconic Preservation and Rum Islands.

Early hours are often windless so we had to motor most of the twenty miles through Banks Strait, assisted by the tide. But, soon forgotten under silent sails, heading offshore to find more wind. Throughout the night, with no other lights, we gazed upon every star while Banyandah slid silently along under the guiding Southern Cross, filling my thoughts of Heaven.

First sunburst breaking the horizon found us ten miles short of Wineglass Bay, behind schedule, begging decisions. Should we head for Schouten Island for a well-earned rest or believe the forecast of increasing winds and take on the remaining forty miles to Orford? In a magnificent life experience, I pondered the decision, balancing the forecasts with likely outcomes knowing we’d the consequences. We’re simple folk, hurt no one, and live on the edge in harmony with Earth. What a fantastic life.

Fortunately, this story has a Hollywood ending. The on and off wind found rhythm just after rounding Schouten Island and choosing to carry on. Calculating we’d probably just squeak into Orford with last light, and thinking it a clear anchorage and manageable in darkness. Instead, that magical wind got stronger and stronger till at lunch, we carried too much sail, leaning over, gripping strong points when dodging spray as we raced towards our destination.

After thirty hours of rocky-rolly life, Banyandah stormed into Prosser Bay, Jude at the helm, bulging muscles mastering the wheel, riding the wavelets into the tranquil bay backed by forested hills. Gee, the yellow grass hillsides reminded us we were now two-thirds around the wonderful island of Tasmania. They also reminded us that getting back to Strahan, the hardest miles are yet to come.

Till Next Time, Stay Safe.

J&J

Closing the Ring

It’s a misty wet Sunday morning and I’m finding it hard to leave my cosy bunk after a long healing sleep. But I’m going to sit up, pull the doona up with me, and tell you about our great escape from Port Davey on Tassie’s SW coast that closed the ring around the Apple Isle.

Prophecy ~

Our last blog ended with a prophecy, “… that getting back to Strahan, the hardest miles are yet to come.” Little did we know just how dangerous and hard those miles would be.

Leaving Orford, our next few voyages were a treat. The kind you dream about when lying idle in the sun thinking of faraway lands. They took us to Nubeena via the bold cliffs along the Tasman Peninsula, the abrupt dolerite columns reminding us of colossal organ pipes.

Rounding Wedge Island took us past the massive array of fish pens lining the entrance into Parsons Bay and the quaint township of Nubeena, where we celebrated a mate’s birthday. What a lovely day that became when his dozen neighbours rocked up with a birthday feast and massive trifle fit for royalty.

Sailing for Untouched Lands ~

Sailing is dictated by the wind, which got us out of bed early the next morning, setting sail for the untouched lands of southern Tasmania, where humanity stands in awe of the creation. No roads or phones for hundreds of kilometres–the only way in and out is on foot or boat–and recently by small aircraft to a primitive airfield first constructed by the King of the Wilderness, Deny King. (Highly recommended book)

Mountainous barriers and raging icy rivers traverse these untouched forested lands with names like Precipice Bluff and Saw Back Ridge and Frenchmans Cap.

Jack and Jude do not fear these isolated outposts of pure Nature. Instead, we relish the opportunity of isolating ourselves from the maddening world and being humbled and awed by the glory of Earth. So we sailed direct, non-stop out of civilization, rounding Tasmania’s South East Cape as the glorious red sun dipped below the sheer walls of the southern shores. Spume and mist faded into one last rainbow as the lighthouse on the last corner of humanity came alight, marking our passage into the wild abyss.

With my lovely wife heading into her 76th year, we pointed our veteran craft towards the darkness, knowing that only the brave and well prepared escape unscathed.

Blessed with a lovely following breeze, we gave South East Cape a wide berth, avoiding the chance of entangling a cray pot, and away from the nasty backwash of powerful southern ocean swells. This helped us keep the fading north wind filling our sails, driving our ship onwards into the star filled night.

Halfway across Tasmania’s forty-mile south coast, the breeze finally slipped away, leaving us floating through the heavens of glittering stars with the single flash atop Maatsuyker Island seven miles dead ahead. I stood the first watch while Jude slept till awakened at 2 AM, then I slipped into her warm bed.

We drifted silently until the eastern horizon lightened with molten gold that gave shape to first one, then another of the islands braving those challenging seas. Treeless, abrupt ramparts of poetic beauty keep the greatest of all seabirds company. Wandering Albatross, curious who would venture where few dare go, glided close on steady wings, their hooked beaks and hunter’s eyes seeming to welcome us to their domain. Watching them glide effortlessly over the sea, I could feel the free spirit of Earth’s wild creatures enter my soul, and once again felt at peace with my creator.

Louisa Bay ~

When a gentle zephyr touched Banyandah’s sails, enough for us to drift forward at walking pace upon the unruffled sheet of grey, we pointed our ship towards a tiny bay lying below the intimidating Ironbound Range. The famous South Coast Track, taking walkers from Cockle Creek to Melaleuca, climbs from sea level to its 900-metre summit over five kilometres before descending to the wide yellow-sand shores of Louisa Bay. Within that bay lies a calm weather anchorage alongside a lonely Island sharing the same name that’s connected to the mainland by a low sandy isthmus, offering some protection from the sea. Having visited this majestic patch of Nature several times, we looked forward to an overnight stop and await a fresh wind to complete our passage to Port Davey.

Once the anchor was down and dug in, we immediately launched our Green Machine kayak for a paddle along the island’s red-rock cliffs topped by a light forest of Peppermint and smooth bark Swamp Gum with an understory of Manuka and scented paperbark. Then we landed on a pebble and sand beach for a wander along its rarely visited shores, immediately spying footprints of little penguins and short-tailed shearwaters. Louisa Island is part of the Maatsuyker Island Group Important Bird Area identified by BirdLife International, the world leader in Bird Conservation; because of its importance as a breeding site for seabirds like little penguins and short-tailed shearwaters, fairy prions, common diving-petrel, Pacific gull, sooty and pied oystercatchers.

The beaches of Louisa Island bewitched us with treasures of seashells, sea urchins, mats of displaced seaweed, and swarms of flying insects that filled several shoreline caves.

Port Davey ~

With a sailing ship, one great treat is waking to a fair breeze that found us hoisting sail as soon as the anchor clinked home and away we went to tackle South West Cape. Our next treat, enjoying morning coffee while the southernmost islands on the Australian continental shelf slowly slipped past. The dramatic Maatsuyker Island Group comprises six islands and two groups of rocks. Maatsuyker, the main island, with a manned lighthouse, is 2.6 km long and just over a kilometre wide, a ridge rising to a height of 284 metres. The Needles, a series of tall abrupt rocks, pop up southwest from it. The largest island in the group, De Witt, locally known as Big Witch, is a place we want to explore. It’s a place that evokes back to basic contact with Nature, with its forests and freshet streams and ungodly beautiful rock formations the likes we’ve seen nowhere in the world. Our only hurdle, the weather and anchoring depth of sixty metres!

As the breeze gained strength, the bold cape facing the might of the Southern Ocean came closer in focus. Even in the moderate breeze, we could see white spume flying high as if deflected off a gigantic ship as we set our fishing gear trolling to capture one of the marauding tunas that hunt off this meeting of currents.

It’s always a treat passing this cape and witness again the sheer cliffs running north towards the safety of Port Davey. This morning was even more special as we carried the wind around it, propelling us north like sea eagles flying fast over the calming seas. Ahead, the strange formations called the East Pyramids, poked up like gigantic seal teeth, long, slender and pointed.

Full sails carried us around them too, into the broad expanse of Port Davey, where we shaped a course for Breaksea Island, the saviour of this sanctuary, blocking Southern Ocean energy from invading Bathurst Harbour.

With our heads filled with the special images of Nature’s beauty, we really didn’t want to mingle with other vessels taking us back to reality. So we chose a quiet spot in Bramble Cove under the colossal might of Mount Misery, a memorable climb from that anchorage.

Unfortunately, we didn’t have time to scale the heights of Misery before the weather turned sour our second day in Davey. Maybe we’d had our run of good fortune, for the bad began with rain and strong winds that only got worse.

A series of rainy gales kept us boat-bound with only a fine day between them, when we’d rush out to scale a mountain or walk to a waterfall or visit the Deny King Heritage Musuem at Melalueca. Getting itchy to do something more made me a little grumpy until I started work on our next book.

African Honeymoon ~

Will complete the series we began with Two’s a Crew and Around the World. With a working title of African Honeymoon, it will take you with two naïve newlyweds on a year-long journey, driving a dilapidated VW van down a continent grappling with independence and rife with wars, looking for a new life in a yet undiscovered land.

Writing books like the ones we produce requires research to paint vivid, informative images, with historical notes and accurate descriptions of the people and geography we visit.

This trilogy is being written out of order because we’re not so professional as to have launched a proper campaign from the onset. For over five decades, we’ve just jumped into new challenges, eager to swim, not sink. We’ve learnt heaps. Neither of us excelled in English, but we found by recording diaries and writing short stories, learning to be a good wordsmith is like learning any craft. Practice, practice, practice, and have something worth saying.

Our intense involvement with Earth and her people led us to believe we have something worth saying.

To us, Earth is the credible proof of a creator. Everything works so perfectly, with such intricate beauty interdependent on balance. In our long lives, we’ve learnt that many people seem to think humanity is the special thing. And that has given powerful forces the opportunity to alter what has kept Earth in harmony since the beginning.

It’s the young we want to reach. They’ll soon be the lawmakers. We’re also reaching out to the wider public because with social media, there is genuine power to make the greedy and anthropocentric change course. A sustainable human population is necessary to protect the natural world and improve people’s lives.

Provisions Looking Thin ~

After several weeks of hiding from storm winds, our provisions started looking thin. We measured our cooking gas, recorded our fuel and fresh water levels, looked into our booze locker, and counted the days we could comfortably last. As a result, our search for a weather window became a little more intense.

Weather Window ~

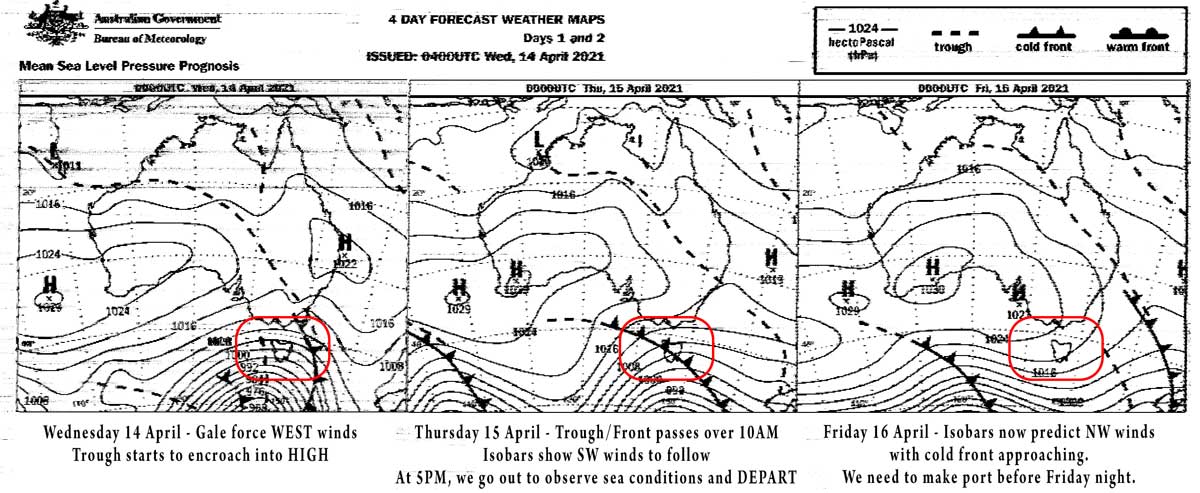

In Port Davey, the weather calls the tune. There is no internet, no phone coverage, only VHF and HF radio. Three, sometimes four times a day we would record the weather forecast, either poorly on VHF channel 68, sometimes more clearly on HF. Such a short forecast period doesn’t allow for planning, so we went back to a system we used when crossing oceans that spanned weeks.

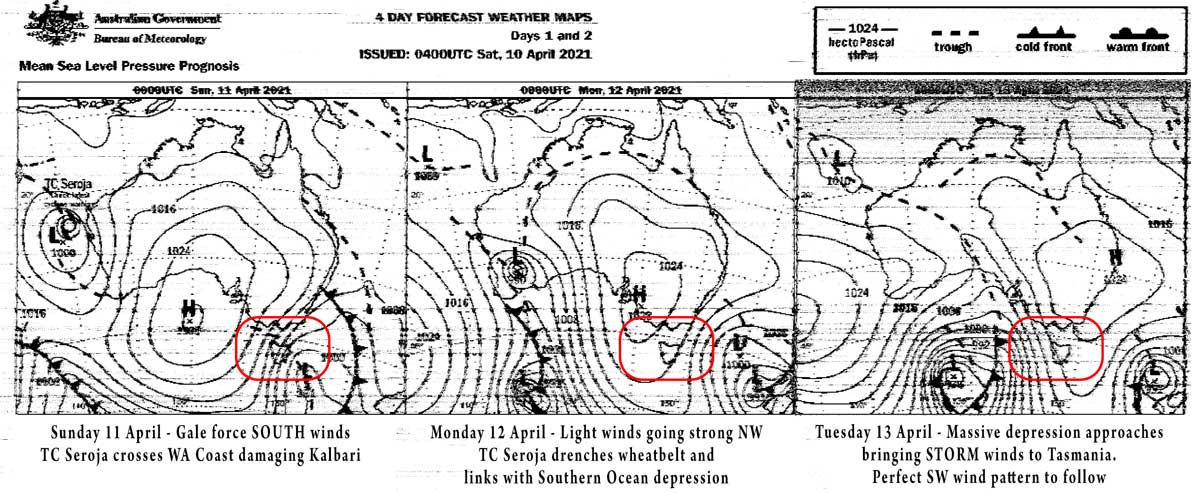

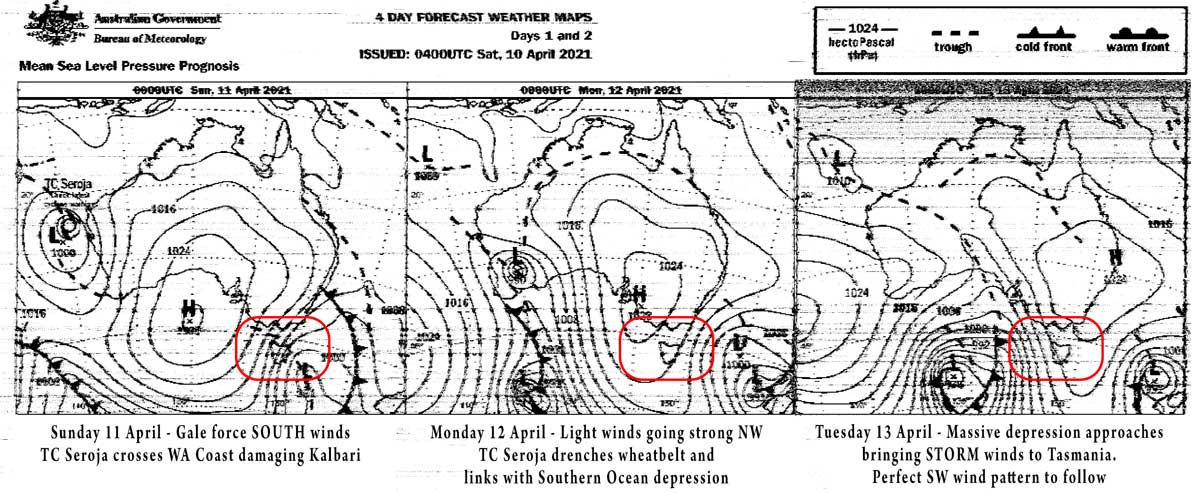

Every day, the Australian Bureau of Metrology issues a series of weather charts on radio fax, which we recorded then sent through a decoder that produced informative weather images. The most useful were the four-day forecasts, just like the ones found on the internet. I could then plot the positions of the highs and lows and figure out what we might expect. The BOM also produce an Indian Ocean chart that shows all the systems that might affect us. Of course, doing this takes discipline and considerable time, but that’s our job—to navigate our ship safely through troubled waters. Over a three-week period, the charts showed only three favourable possibilities to sail north.

What we needed to get safely around the obstacles on the ninety-mile voyage to Macquarie Harbour were southwest winds. The course to Low Rocky Point is the first and most demanding, requiring a ship’s course of 310 True. Our lady is no racing machine. To be effective, Banyandah needs to point at least 50 degrees off the wind. Less than that, she stalls. But sailing that tight in the Southern Ocean might break something. Preferably, we’d like the wind to come across our beam, especially in heavy weather. That meant we needed a true south-westerly.

Not wanting to bore you, here’s how it works in southern latitudes. The wind in low-pressure cells rotates clockwise; in high-pressure cells, wind rotates anti-clockwise; the systems feeding each other like a figure of eight. The first touch of a depression-a low-pressure cell-comes with wind from the north-west. As the centre of the depression gets closer, the wind backs to the west. Then there is a short period as the centre passes over, when we get the desired southwest wind. The situation with a high-pressure cell can be much better, especially when the centre of the high-pressure cell is north of us and the cell elongated in a SW/NE direction. That’s what we wanted. A long period of mild SW winds bringing clear skies and settled seas.

After measuring our remaining stores, we had three promising weather systems that turned into dangerous conditions in the last days before reaching us. One system had looked so good, we imagined stopping midway for a wander around Pyramid Island to visit the seal colony at Hibbs Point. But tropical cyclone Seroja spoiled that by racing across Western Australia to link up with a nearby low-pressure cell to produce a monstrous northwest gale that forced us to secure our vessel against horrid storm winds. We got little sleep the night it passed overhead.

These events went on and on. Each time dashing our hope of escape. But it was important to take a positive view or the moody blues would spoil our life. Jude and I kept at our projects, researching information in our electronic library, interspersed with jaunts on shore in between the storms.

Hopes Rise ~

On the 14th of April an oblong high appeared on our weather chart with widely spaced isobars, indicating easier winds from the southwest. Our hopes rose. We might escape. Even if we got light winds, we were ready to motor all the way back to home base.

Our heightened hopes slipped the next day when the next chart showed a small trough intruding into this high-pressure cell. But the angle behind the trough still looked perfect, so we started making preparations.

Next to us during our wait, we got to know a charter vessel with six brave passengers who went out each day in wet weather gear to gander the extraordinary Port Davey landscape. Their last night before flying out coincided with our last night, and they invited us to a dinner party on the large motor vessel.

Just what we needed. Laughter, storytelling, contact with other folks not dependent on wind and sea conditions. We even had hot showers.

Out for a Look ~

All that night, it blew strong NW. Next morning, the trough passed over around 10 AM, bringing hail and showers. We made final preps; lashed the oars in the dingy, organised the emergency safety gear, checked the grab bag. I gave our ancient engine a drink of oil and a good look over the belts, pumps, and couplings.

The early morning weather report mentioned a change to SW winds after the trough. So, at 1 PM, we started our engine, just as the bosun ferried his passengers away for their flight. As our engine warmed up, the vessel’s other tender pulled alongside with the skipper and chef, who called out, “Happy Birthday, Jude,” as he handed up a large bag containing their leftover food.

“Oh Wow! Thank you very much.” Jude beamed as I lifted it aboard, noticing a loaf of bread, lots of leafy vegetables and other treats.

The skipper raised his eyes skywards to grey scudding clouds. “Not what you hoped for,” he said, running a hand through his thinning hair.

Shaking my head, I replied, “You’re right. At 6 AM, Maatsuyker reported WNW winds of 49 knots.” Then managing a weak smile, “But that was before the trough passed. Last night’s isobar chart showed the wind going south of west. So we’ll go have a look.”

The skipper looked to the birthday girl, “How you feeling?”

Jude grinned. “Yeah, good. It’s all the planning and looking at weather reports that get me down. But now that we’re going, I’m excited. Can’t wait.”

Ten minutes later, both parties went off to meet their destinies. Wondering if their plane would brave the elements, we motored over to Bathurst Narrows, where we met our first nemesis, a nasty chop straight in our face. This we handled in our normal calm fashion, using the shore shoulders for protection where we could. But it took much longer than planned to reach the end of the seven-mile channel, reaching Breaksea Island late in the day. Through binoculars we got our first view of the open bay and knew a battle lay ahead.

Strong winds create enormous seas that rebound off headlands and rocky shores to collide with the incoming swell, creating a confusion of forces.

Drama Clearing Obstacles ~

We needed to gain ground on those winds to clear the obstacles awaiting us on the far northwest side of the bay. First there’s North Head, a steep rocky bluff creating mountainous explosions of white water. Further out, another lot of towering seal teeth erupt, the West Pyramid and Coffee Pot. Foul ground around them, shallow stuff, breaking horrendously.

Businesslike, Jude drove our adventure machine down the narrow cut between the rock shores of Breaksea Islands and equally dangerous rocky mainland while I worked out how to rig the third reef in our mainsail. Something we’d never done.

This is when you need cool thinking. Screeching wind, crashing waves, rocks on either side while trying to do something not done before! Jude, dear heart, kept Banyandah bashing straight south down the narrow alley, asking for reassurance every few minutes. Each time, I assured her we had room to turn about and sail back.

“And steer a little left! Give that breaking water off Shanks Island a bit more room.” I shouted from the foredeck, still trying to attach the third reef tack with a new strop. Once in place, I hoisted the mainsail, nearly losing the halyard to the strong wind and horrendous motion. It looked tiny.

Amazingly, all went to plan. We made it down the alley into open water near Spain Bay, then hugged that southern shore, slipping north of Nares Rock into open sea.

When we lost all protection from the land, I ordered Jude to lay a course to clear the Coffee Pot then released a third of our furling headsail and together we cranked it in as tight against the rigging as it would go. Our nose pointed just seaward of the breaking rocks.

As if our lives depended on the outcome, we watched our progress across Port Davey Bay, noticing our ship steadily losing ground to the washing machine seas. My heart sank and my mind went into overdrive thinking we’d have to turn back. We’d not make the corner.

In our long sailing career, we have faced several life-threatening moments. Some caused by my error of judgement. I don’t give up easily. With a slender new moon bright amongst the heavens growing dimmer, I’d keep us going unless forced to turn back by unmanageable forces.

Fighting Nature is futile. She’s not our enemy, but a natural force that deserves respect. So while Jude continued to do what she loves best, guiding our ship, I scanned the obstacles ahead through binoculars while pondering the best course and decided we’d carry on until the breakers ahead became a clear and present danger. Then we’d try to go seaward under engine alone.

Still with a safe margin, we furled the headsail, cranked the mainsail in tight, then gave the engine her moment to make the voyage north possible, knowing we could turn back.

Quite impressively, our engine, circa 1950, pushed Banyandah through mountainous waves with a steady deep thrum while we watched the breakers on the furthest Coffee Pot slowly slip past.

Away for Low Rocky Point ~

When satisfied with our clearance, we switched on our bright deck lights for a thorough inspection of our craft. After everything looked to be in order, I set to work increasing the size of our mainsail, shaking out the third reef to secure the second. Then Jude laid a course to a waypoint six miles seaward of Low Rocky Point, our next obstacle along that hostile coast. With the wind coming at us forward of the beam, we unfurled about half of our workhorse headsail.

From that point, returning to Port Davey became much harder.

In the next eighty miles to home base, we must clear two points of land. The first, Low Rocky, would be the hardest, requiring the tightest angle on the wind, which now that we were clear of land proved not to be from the south-west as expected.

Strong winds and rough seas challenge a yacht. With sails pulled in and the rig bowstring tight, we rattled and hummed, and Banyandah’s scant few tonnes shook when smashing into head seas. In the night’s blackness, that created worry. It was impossible not to think about what we’d do if a catastrophe struck. Call for help? What good would that do in the lonely southwest of Tasmania? The water is freezing cold. The seas over seven metres. The rocky shore so close we could hear the death drums of breaking seas pummelling the shore.

The best and only course is to keep a clear head, check our vessel and identify every noise to ensure there are no lines chafing, no sails overstretched, no rigging working loose, nothing that might suddenly let go. Then relax a little, so our minds can cope; and if possible, enjoy the moment. Working with the unbelievable forces of Nature is both humbling and uplifting at the same time.

Shortly after clearing the Coffee Pot, I sent Jude to be bed, not that she’d get any sleep in our violent crash and bang, but she needed rest after her day at the helm. So would I in a few hours. Then I jammed myself in a corner of the settee where I wrapped a warming blanket around my frozen feet. Seems my boots, pants, and thermals filled with seawater during the action.

Twenty-five hard wet miles on a close-reach took us to our waypoint six miles off Low Rocky Point Lighthouse, which, by the goodness of karma, we reached at one AM. Its single flash gave me great satisfaction when I thought we’d almost given up.

Jude and I then swopped positions. Me into her warm rocky-rolly bed. Jude into the cold to keep lookout and keep us tracking for our next important waypoint. While I rested, she did a marvellous job of gaining a couple extra miles to weather while maintaining ship’s speed. When I arose, Banyandah was tracking ten miles off Hibbs Point with our destination Cape Sorell lying due north, only twenty-five miles away.

I’d love to write that we were safe. But Nature is always in command and let us know this in the 6 AM weather report. An early change would arrive before noon, a change back to the northwest that would strengthen into a gale by nightfall. By this time, the seas had settled into a regular rhythm. Seabirds, both the erratic flying mutton-birds, accompanied by graceful, aloof albatross, began skimming the wave tops looking for breakfast. The wind started easing.

Having come so far, conquering so many obstacles, enduring anguish, and ageing a hundred years, we’d not be turning back now! So, while Jude slept like a princess, I fired up our trusty Perkins P6 diesel to assist the dying wind.

When our speed went from 2 to 3 knots to touching 6, sometimes 7, I went below with a cheeky grin to make a coffee and a bite to eat. Aargh! Pirate Jack doesn’t go down without a fight.

These seafaring dramas often end in a whisper rarely apparent at the beginning. Our hours spent planning for a disaster, analysing choices versus outcomes, fade so quickly when your destination comes into view, that it’s easy to forget your lives were under threat only hours before.

Success ~

This salty tale ends on a high note, not only of success but also, instead of battling a fierce outgoing current as expected through Hells Gate, Banyandah coasted into safety at high speed. Heavy rains and a rising barometer normally send water out the Gate at up to a hefty five knots.

A few hours later, upon securing our valiant lady to her mooring, we raised a glass of ale to toast each other’s mighty efforts and gave a cheer to our stout homemade ship. She’d performed admirably, keeping us safe so that we can set out yet again on another adventure. But then our weakened legs wobbled. And we felt the aches and bruises that blushed purple. So we dragged our weary bodies below for a well-earned sleep that lasted thirteen hours….

Wrap: Port Davey has been very inhospitable since we escaped with a continued cycle of heavy rain and nasty gales. Meaning we’d be sodden and miserable if we hadn’t made the break.

Till next time, wishing you good health. Keep a keen eye on Covid. We’re not safe until we’re all safe.