| HMS The Investigator |

In flickering candlelight, the boatswain’s mate wet the delirious man’s brow as he lay shouting “Mary, Mary, I love you.” Then with a sigh the man’s head slipped sideways into silence. From between darkened decks, a sickly figure ambled forward resplendent in gold braid. “How’s the boatswain,” he wheezed. The mate simply shook his head.

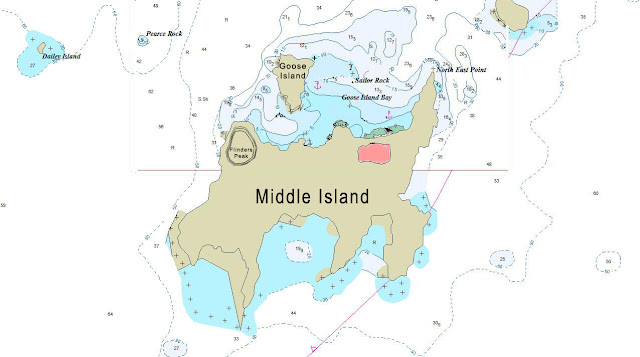

In the dim light before dawn, Charles Douglas, of His Majesties Ship The Investigator was sewn into a piece of old sail, loaded into a long boat then hauled onto the low slopes of the recently named Goose Island. There, before an assembly of his shipmates, Captain Flinders read the eulogy. “Charles Douglas was an honest man who served God and his country. He will not be forgotten.” The year was 1803.

“Hey Jude,” I called forward from my writing desk. “The Investigator’s bosun is buried on Goose Island.”

She joined me in the cockpit and together we looked across the bay. “Any idea where?” she asked.

Overnight, cool air from Antarctica had driven away the heat haze of several days, and now the sand hills surrounding Cape Arid stood crisp white against unblemished sea and sky. On our left, rising sharply against a tiffany sky, Flinders Peak dribbled old blood streaked with sunshine. Between the two, Goose Island emerged, a low emerald from a sheet of sapphire.

“Where,” I laughed. “All the guidebook says is his grave was inscribed Charles Douglas HMS Investigator May 18, 1803 when discovered in 1999.

Instinctively our eyes searched that mile long island as I added, “It doesn’t say where. But my guess is it’ll be close to a landing and probably face the rising sun – that’s where I’d like to be laid to rest.”

“Shall we go and look?” Jude softly asked like a schoolgirl seeking a treat.

“Sure! But first let’s shift Banyandah. What a thrill it’ll be to touch something from The Investigator.”

Beyond the limestone cliffs that ran towards Middle Island, a finger of white sand sparkled beneath bold Caribbean blue, and where sand met sea, a picturesque limestone arch rose. Jude became radiant, a distant memory dancing in her eyes. “Reminds me of Ventotene,” she trilled, and I remembered making love on just such a beach, hidden inside just such a cave while the sea lapped our feet.

“I’ll row now,” she declared. “Those spooky caves and limestone teeth will look great on film.”

So we switched places, and while she pulled the oars, I watched her breasts rise and firm, and that sent my mind back to the cave.

Rounding the craggy headland a perfect white beach ran a hundred metres before reaching the channel between the two islands. Assisted by a low surge we grounded then quickly dragged our dinghy up the hard sand, where I immediately documented our landing by panning from the beach through the archway to Banyandah tugging at her anchor.

“He won’t be buried here,” I declared, looking to Jude brushing sand from her toes, her socks and boots standing ready. “The grave wasn’t discovered for nearly 200 years, so it won’t be next to the only decent landing site.”

D’entrecasteau first recorded these islands in 1792 naming the archipelago after his ship, The Recherche. Later explorers mostly avoided the area because it is littered with 105 islands, and over 1200 “obstacles to shipping” jutting out the sea. It’s far flung from mankind, without any roads near. No need. The ground is sand or rock; no resources of note. It’s a place for Earth’s other creatures, and boy, do they abound in variety. Each year flocks of seabirds come here to reproduce. They live underground in burrows dug by beak and webbed feet, and each year they return to the exact same hole.

Flinders wrote of the sky being turned black for hours by their passing millions. However, today, though man doesn’t hunt these creatures anymore, their numbers are greatly reduced. Why? Because we take their food. We harvest whole schools of pilchards at a time – to feed our cats, or the tuna we capture and keep in nets. It might help if we remember that every form of Earth life is connected. What man takes makes another suffer.

Picking our way carefully, we wended past bushy tea-tree and sharp scrub, towards a rock shelf rising up the weather side, avoiding mutton bird burrows that spread ahead like a minefield. Between them on the bare earth we saw tiny shuffling footprints of little blue penguins that also live on the island. Surprising us next; we found large areas of round spoor, and prayed it came from small marsupials. But shortly were disappointed to catch sight of a small rabbit bobbing away.

“Pretty one, that,” Jude exclaimed.

I’m sure she was thinking of her childhood pet, because although this one had lovely black fur tinged rusty gold, we both knew it was a disaster. Memories of totally denuded islands came to mind.

“Wonder how they got here,” I mused, shaking my head. They’re so destructive, firstly destroying the moist refugia around rocky outcrops causing the decline of medium sized mammals and then as their numbers increase, they devour all plant life. Like humans nibbling away, first along the edges of wilderness, little bites till there’s none left.

Along that shelf we travelled the weatherside, watching glorious blue sea bursting white on rocks while traversing higher in the direction of an eagle’s nest. Then as we crested the ridge, the nest became an immense rock cairn atop the island’s peak. Jude added our stone, having to hitch herself up on a big stone to reach its top.

“I see what you meant,” Jude said. “I agree, Charles would more likely be interned on that ridge there, or that one,” she said pointing to two fingers running parallel in line towards our ship. “The Investigator would have parked just a bit further out from us.”

I agreed but suggested, “If you like, let’s first explore that cave. See? High up that rock mass at the far end, and then we’ll search for Charles on the way back.”

Exploring a far distant island turned us retirees into children by energising our spirits. The air carried more vigour; our eyes noticed more detail, our minds asked questions, and we soon forgot our aches.

The cave proved no more than an overhang popular with sea birds. Fish bones littered the earth among a white carpet of excrement and shattered sea shells. But around it and spreading up a shallow valley was a carpet of gorgeous succulents the colour of fire at dawn. Polyps, billions of them. And while filming this grandeur, Jude with her backpack like the hunchback of Notre Dame frightened a massive wedge tail eagle into flight so that the parade of colours and action through my lens made me gasp.

When only three fingers of sky separated sun from sea, it told us to hurry or spend the night surrounded by noisy penguins. Heading home through the low slopes of brush, every step brought new hope of stumbling across Charles. Over and over I imagined how I’d react to finding a direct link to The Investigator, while in my head ran the constant chant of “I’ve found it!”

What would I first see? A headstone? Probably not. More likely a neat pile of stones. The island had had two hundred years of growth. Those trees nearby were not here then. And Charles could lay at rest under them, or under any of the thicker growth.

Finding Charles became hot, sticky work, hopeful, then disappointed. Finding a metal stake set my heart racing. It led to another by some trees and the words of discovery were ready to fly from my lips. But all I found were half buried plastic bins being used for some sort of scientific experiment similar to those we’d seen on other islands. Catching rats I suppose.

Exhausted, sweaty, thinking of a shower and cold beer, totally spent from our day’s excitement surrounded by Nature’s beauty, we began talking of rowing home. Finding Charles may not have been meant to be. Rest in peace Charles Douglas.

A humorous footnote to this adventure came when we emerged from our communications vacuum here at Cape Le Grand, 25 km short of Esperance. Now able to connect to the worldwide net again we did a search for Charles. He wasn’t easy to find.

He had died of dysentery on board The Investigator as they approached Middle Island and Flinders had named the island nearest them in his honour and we had seen Douglas Island when we sailed away. But his final resting place? Aaah! Our guidebook had it wrong! It was May 1803, the winter seas big, and Flinders’ crew were sick and weak. Even the captain couldn’t land on Goose Island, so Charles was interned behind the third bay of Middle Island. And you’ll be amused to read that we had parked right by him the following day, and had walked within cooee of his grave during our jaunt up Flinders Peak on Australia Day….. What a marvellous wild goose chase!