November 2021 September 2021 >>

Blog of Jack and Jude

explorers, authors, photographers & videographers

Summer Gems

A long Covid winter sharpened our need for adventures far away from viruses, media, and authority.

So, Jack and Jude have put together a bevy of the best adventures we’ve experienced around this great country of Australia – where sailors do not need passports nor port clearances to sail around the world’s longest continuous coastline.

Wild Stopover at Investigator

Facing the Great Southern Ocean, this remote outpost for nature begged to be investigated. So, we planned to anchor there overnight if conditions allowed. Lying 55 miles west of Esperance, and 15 miles from the mainland, the Investigator Islands, which were originally called Rocky Isles before being renamed to honour Flinders’ ship, are only two gigantic granite boulders rising out tempestuous seas.

1802, Matthew Flinders wrote, “Rocky Islets (Investigator Islands): low, smooth, sterile, frequented by seals”

These are the furthest west islets in the Recherche Archipelago, which contains many unsurveyed areas. Therefore, on full alert and using our chart only as a guide, we sailed into a bay surrounded by rising granite islets after first skirting the shallow patch off their head. With extreme caution, we edged in, expecting the bottom to rise suddenly. Looking about, we saw no sand beaches. Just steep bare rock, so it did not surprise us to have to sink our anchor into great depths.

34°04.39’S ~ 120°52.14’E

Reasonable shelter from NE through S to SW

Banyandah anchored using an admiralty anchor in 17m sand.

Once settled, our next look found sea-lions loitering on the rock slopes. We didn’t mind being too late to row around because in half an hour the sun would melt to liquid gold behind black rock, providing great scenery from our floating home. And so, we watched a group of NZ fur seals cavorting in the rocky gap between the two islets, their dark shapes contrasting starkly against the white breaking southern ocean swells seething with foam. Through binoculars, their dripping wet coats reflected the miraculous glow of the golden sun across which sea-birds were flying home.

Gently rocked to sleep, then awakened by intensified wind gusts through the gap between the islets, we eventually slept well before early yelps of seal pups demanding a feed dragged us from our bed. Our radio forecast light winds to increase after lunch, and with shafts of sunlight already peeking through the morning cloud, we quickly moved to launch Little Red. Expecting to land, we packed shore gear, but our first two attempts had to be aborted. The first time, Jack got both feet out of the dinghy only to stand on such slippery sloping rock, he didn’t dare let go. No choice but to jump back in before a swell swept us back into the bay. Lucky him.

But we got ashore. Jack had seen a nick behind a large rock and chanced rowing on a surge over a rock shelf that ended in a perfect harbour hardly bigger than Little Red. We scrambled off its stern onto a very flat, dry rock standing knee height above the water, then hauled Little Red up after us.

Daw Island ~

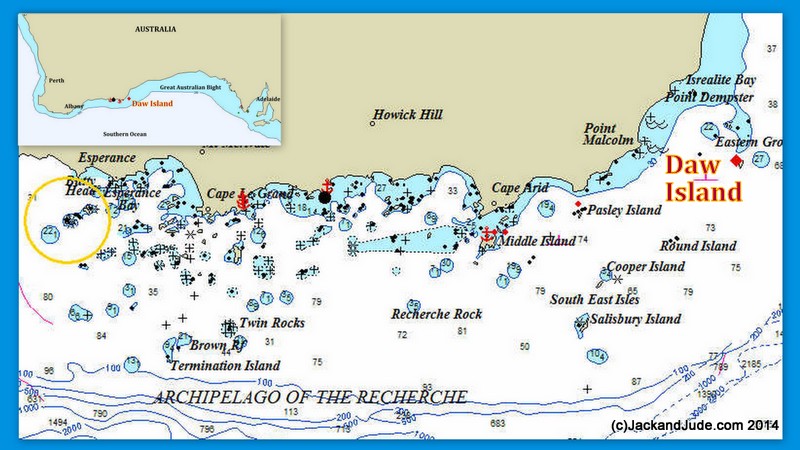

We’re guessing that you’ve never heard of this droplet of land that pops out the turbulent Southern Ocean twenty miles from Isrealite Bay in Western Australia. A few years ago, we sailed past it on our way west, but didn’t stop as we had wind for many more miles. So this time when going east, we were keen to explore Daw Island. Especially after Ted, our tuna fisherman friend in Albany told us that Daw Island once had a tuna processing ship stationed there during the fishing heydays of the 1970s.

Today Daw Island is an outpost of Nature, a lonely island at the very eastern end of the remote Recherche Archipelago, impossible to visit without a stout vessel and the courage to face Australia’s south coast. Very few visit, mostly fishermen and few yachtsmen, but hardly any pleasure boats venture out that far from help.

Today Daw Island is an outpost of Nature, a lonely island at the very eastern end of the remote Recherche Archipelago, impossible to visit without a stout vessel and the courage to face Australia’s south coast. Very few visit, mostly fishermen and few yachtsmen, but hardly any pleasure boats venture out that far from help.

At Daw, Nature dominates. And that makes this place special. Cute comical sea lions, majestic sea eagles, plump geese, muttonbirds, penguins, and deadly snakes all coexist with a myriad of other birds and critters living away from man and his needs. At Daw Island, these creatures raise their families unmolested.

In our adventure machine we have traveled far and wide to find Nature living where man does not exist. We sailed to the middle of the Coral Sea to observe thousands of sea birds undisturbed by man. This time we pitted our skills against the wild Southern Ocean that can create gigantic waves from storms gathering fury in the freezing waters of Antarctica. Down under Australia, far away from the built up centres of Albany and Esperance, there are a thousand islands. Some just rocks partly submerged but still home for many creatures.

Our sail to Daw was perfect, except we often altered course to dodge tiny rocks jutting from the ocean. And we were frightened and in awe when great swells broke over underwater shoals we couldn’t see. But the wind held, and forty miles on Daw became visible as a dull grey shadow with white water flashing high into the sunlight. Still flying full sail after forty-eight miles, we were conning our way into calmer water, Jack atop the coach house searching for hidden dangers.

Shaped like a boomerang, Daw Island has tall massifs, but is not surveyed. Its sister island, New Year, is only a pinprick on navigational charts. On the slopes before us, the sun lit up the bright red, yellow, and orange colours of succulents.

Shaped like a boomerang, Daw Island has tall massifs, but is not surveyed. Its sister island, New Year, is only a pinprick on navigational charts. On the slopes before us, the sun lit up the bright red, yellow, and orange colours of succulents.

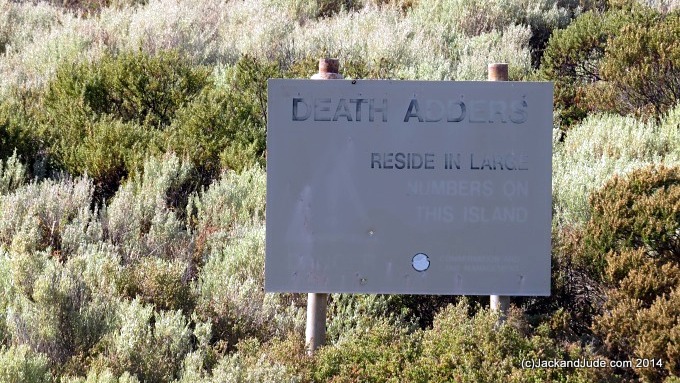

Death Adders reside in large numbers on this island.

Donning thick walking pants, boots, and wet weather gear we landed on the only sand beach and straight away noticed a sign warning of deadly snakes. We know a bit about these creatures, so Jack cautiously took the first track thorough shallow bush that lead to another then another until we reached the saddle looking both to windward and into our anchorage. The Banyandah looked so beautiful all alone in the half cauldron, while on the weather side occasional white caps on a slate-grey sea below a leaden sky drew our attention to an approaching black curtain of rain. Feeling the invigorating fresh breeze fired up our desire to reach the island’s highest peak and along the way our cameras captured gigabytes of this beautiful Earth.

Rain came just as we reached a rock cave near the end of the main island, and ducking under its crude cover we watched several Cape Barren Geese honk and gesture while trying to figure us out.

High overhead, a pair of majestic sea eagles soared as if they owned the sky. They were using Nature’s forces to swirl and look down on everything like the very best spy camera. What a life. No bills to pay. No bureaucratic red tape. Mating for life, sharing the same hunting range, in the morning and evening, they would roost together and sing. While, at other times, they would soar on Earth’s energy to spot a tasty treat. And then their super sharp talons would lift enormous fish from the sea. They are indeed talented, unique creatures.

White-bellied Sea Eagles, Australia’s second largest raptor after the giant Wedge Tail Eagles, is listed as Threatened in Victoria and Vulnerable in South Australia and Tasmania. Their main threat, human disturbance to its habitat, both from direct human activity near nests which impacts on breeding success, and from removal of suitable trees for nesting.

The adult White-bellied Sea Eagle is a distinctive bird with its white head and breast, and tail. Their upper parts are grey and the black under-wing flight feathers contrast with the white coverts. Like many raptors, the female is slightly larger than the male, and can measure up to 90 cm (35 in) long with a wingspan of up to 2.2 m (7 ft), they weigh 4.5 kg (10 lb). Their call, a loud goose-like honking.

After the shower passed, Jack eagerly pushed up the last ridge connecting the two peaks, with a part of his route following a rock ledge that fell sharply into the sea. That might prove dangerous for Jude’s wonky knee, so she took a higher route through scrub where upon putting an un-gloved hand down for support, a snake struck at her. You can imagine her fright. Daw Island is a long way from help.

NOTE: Daw Island did not plot correctly on our CMAP charts.

Masillon Island ~

32°33.76’S ~ 133°16.99’E

32°33.76’S ~ 133°16.99’E

Shelter from E to S in 12 m sand bottom with weed patches.

A fisherman in Coffin Bay told us that this was his favourite spot, but our first sight gave us the shivers. A deep and narrow gully facing slightly north of west ended in a cliff face. Ocean surge breaks both sides of the opening, but all is serene up near the cliff, even in 20 knot SE winds. There are numerous caves. After one comfortable night, we were away across the Great Australian Bight. NOTE: Masillon did not plot correctly on our CMAP charts.

Inhabitated Places We Love

ALBANY WA ~

Friendly and picturesque Albany, the oldest city in WA, beautifully cocooned in a lucky cloverleaf of three connected natural harbours. Discovered by Captain George Vancouver in 1791, there are numerous marinas and beautiful anchorages. All supplies and services are available, plus excellent restaurants, a healthy climate and friendly folk. There’s also a Saturday morning farmers’ market, first class walking tracks, and camping in the nearby ranges. A favorite of ours, the world famous Bibbulmun Track passes through town with camping in SW State Forests all the way to Perth.

Flinders Island WalkAbout ~

Jude and I have often been to Flinders Island, sometimes experiencing stormy weather, sleepless nights, dragging anchor with rocks astern. On this occasion we lashed Banyandah to a stout mooring provided by Garth, Lady Barron’s helpful Harbour Master, and then under a empty azure sky we chucked our loaded rucksacks into Little Red to row ashore to seek new adventures.

Breathing like Puffing-Billy along Lady Barron’s Esplanade, the excruciating weight of our sacks was soon extinguished by the blue of Franklin Sound serenely dotted with blanched granite islands splashed with red lichen. All was silent. Not a soul in sight. No life until reaching four corners and the road out of town.

Jude and I have hitched rides since we first met in the 1960s. Why bother, you might wonder? Renting a car has to be easier. That may be, but we like to meet the locals, one on one, in their environment. Doesn’t matter if it’s inside a dusty ol’ ute, or inside the plush interior of a Fairmont carrying a father and son, like our very first ride that morning.

Meet Robin, a fifth generation Flinders Islander who retired after serving his community as Works Manager, and his son Peter, who now lives in Brisbane. Peter misses the island, so together they bought a boat, and once a year during Peter’s holidays, they go out fishing every day they can. Would we like to see their boat? How about a sandwich for lunch?

Furneaux Museum

Robin and Peter made sure we arrived at the Furneaux Museum just as Kat, volunteer that day, opened the door at 1 pm. $4 entry – what a bargain. Being her first customers we stood at the counter for a good half hour discussing island history – a very rich history indeed.

At 5 pm closing, Kat suggested we wander down to Emita Beach. “There’s a pretty spot with a picnic table and perfect campsite.”

At 5 pm closing, Kat suggested we wander down to Emita Beach. “There’s a pretty spot with a picnic table and perfect campsite.”

So, after refilling our water containers, we took her advice and found heaven. On a point overlooking the blue expanse of Marshall Bay we pitched our tent, and then with tin mugs full of port wine, we wandered along the sand, sometimes casting a squid jig to test our luck.

Black Man’s Houses

Next morning we meandered down a dusty road past plenty of road kill, following white bones and death to Wybalenna, another tragic site at Black Man’s Houses. There in 1834, on an expansive open plain, the British had tried to halt the annihilation of Tasmania’s Aborigines by shifting the last 135 off mainland Tasmania and resettling them on Flinders Island. Where, as George Augustus Robinson noted, they would be ‘civilised and Christianised.’ Forbidden to practise their ancient ways, they became homesick for their lost country and many died from white man’s diet, beliefs and diseases.

In October 1847, the 47 survivors were transferred to Oyster Cove, near Hobart. It was springtime, but even the warmer weather did not hide the fact that their houses were little better than slab huts in poor repair, built in a cold, damp, depressing place.

Killiecrankie

Hitching a ride with a young rancher, who admitted he only lived a minute up the track, but took us all the way to the scenically magnificent Killiecrankie, where we met a group of modern day explorers and swapped stories around the BBQ.

On our fourth day, after walking around the bay to be directly under Mount Killiecrankie, the only distraction from the world’s most perfect campsite was a tiny grit of granite in Jude’s eye and slightly larger ones in our tent.

Behind us rose a smooth rock monolith that seemed to bestow great power while before us spread a blue so tranquil our bodies went limp as our eyes feasted on the parade of buff granite and dazzling white sand beaches backed by vibrant scrub greens. All mixed together by Nature’s deft hand to form a perfect setting for an ashram. You might think this hyperbole, but come to Killiecrankie on a fine autumn day and judge for yourself. The day was so still and warm, we stripped naked and floated free in a transparent world. Then giggling like children, we raced the other back to our tent for some quiet time.

Surrounded by unaltered Nature, we lay with views out both sides, letting our minds wander over our walkabout and wondered how Earth-life had become so complicated. Man’s greed and ineptitude have always walked alongside our brilliance and determination. And throughout humanity’s history, we have nibbled around the edges of Nature like a cancer. And just like a cancer, it is our rapidly increasing numbers that are creating enormous problems.

Till next time, wishing you good health. Keep a keen eye out for Covid. We’re not safe until we’re all safe.