This blog has got to be fast and furious to match the speed of events this last month.

Plenty of miles under the keel with more tough ones ahead.

Happy Birthday Wendy and Barry ~

First off, we want to wish a Happy Birthday to good friends Wendy and Barry. There’s a big bash at their place tomorrow here in Nubeena, and we’re looking forward to sharing a good time with friends. But, we’ll have to keep ourselves in check as it looks like we’re going back to sea early the following morning. The weather dictates our movements around this island, and for a limited time, a whopping big HIGH is generating heaps of northerly winds and beautiful sailing.

Furneaux Group ~

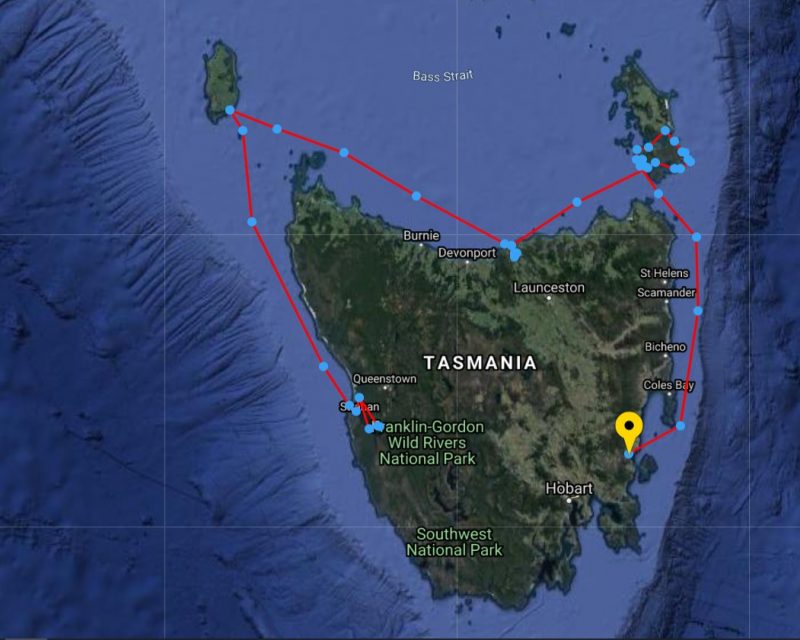

Ending our last blog, we had given our mast three generous, well-needed licks of enamel in the Tamar, finishing just as a handy westerly breeze ruffled Bass Strait. So we hoisted sail late the following day and voyaged overnight to the Furneaux Group of islands to meet up with new friends John and Geraldine. We first met them while clearing the Goulds Track, miles away from other souls, when they had followed our pink ribbons from Sir John Falls, which is twenty miles up the remote Gordon River on Tasmania’s wet west coast.

John and Geraldine on Goulds Track

Leaving the Tamar River late in the day, our course took us east to one of our favourite spots, Preservation Island, in the shadow of Cape Barren Island, with the wreck of the Sydney Cove, beached there in 1797. These Bass Strait Islands are challenging because there are no all-weather anchorages. Instead, troublesome ribbon grass grows thick just about everywhere causing havoc for anchors, plus there are gales a plenty. The NW wind filling our sails, the harbinger of one.

Gale Number One ~

Not only is Preservation dominated by impressive granite tors, the sand patches at Hamilton Roads are handy spots to hang out a westerly gale. Our first striking the day after arriving. A day and evening of screeching winds blew through, then we awoke to a day of total bliss. Overhead, a perfect bowl of washed blue filled with crystal-clear air made every view a masterpiece of supreme scenery. We packed a lunch, then launched Little Red to go walkabout and revisit historic spots. The lookout of circular stones built by marooned hopeful sailors commands a view over Armstrong Passage, this day a masterwork of isolated beauty in every shade of blue. Right below the lookout, up against four gigantic wheat coloured granite tors, the survivors built a camp from torn sails, where archaeological remains have been unearthed. Today, these historical remnants are on display at the Queen Victoria Museum in Launceston. Well worth a visit, or peruse Michael Nash’s well-illustrated book, “Sydney Cove.”

Easily tramping through waist high undergrowth, we next came to the waterhole dug in 1797 on this otherwise waterless island. Rainfall must be scant, as this was the first time we’ve seen the waterhole dry. From there, over a slight rise passing between two more gigantic granite outcrops, these splashed with orange lichen, we came to the magnificent Store Beach, named for the stores landed there during the days after the ship’s grounding. The sand is a lovely beige running to pure white above the tide line. Blemish free as if the Creator had just completed it before adding a couple of decorative mini tors, one with a balancing stone atop that adds further wonder, watching to see if it topples in the wind. From this vantage point, the final resting place of the Indian built Sydney Cove can be seen next to a rock that pops up close to a little island, named Rum Island by historians as it kept the many gallons of salvaged spirit away from desperate sailors. A splash of translucent Caribbean blue separates the two islands, making the view a picture-perfect postcard.

Those of you wanting to read the whole fascinating saga of this historical event that also includes the first overland walk by white folks on Terra Australis, best find a copy of “The Wreck of the Sydney Cove” by Max Jeffreys.

Gale Number Two ~

A light breeze introduced its coming, prompting a shift of a few miles north behind Wombat Point on the south side of Cape Barren. We’d been there before and remembered dragging anchor one windy night before exploring its hinterland. Our topographical map shows a shallow lagoon just a few hundred metres inland, tickling our curiosity. So, we dodged through skinny water until laying a few hundred metres off the sandy shores, then launched Little Red for an upper body workout rowing in.

Cape Barren is an Aboriginal Island whose cultural centre is a tiny pocket called The Corner on the north shore. The population of the island numbered 66 in 2016. There are few roads, and few 4WD tracks, those mainly to fishing spots. Wombat Point Bay held one thin line leading to The Corner, but we saw no signs of habitation, just seagulls and us. Pushing through shore scrub, we stumbled upon a disused track and followed best we could until breasting a rise to an impressive kilometre long dry pan that held a small pocket of reedy water at its eastern end, filled with ducks. Squawking plovers lined the shoreline, holding a gala jamboree, courting the young pretty ones.

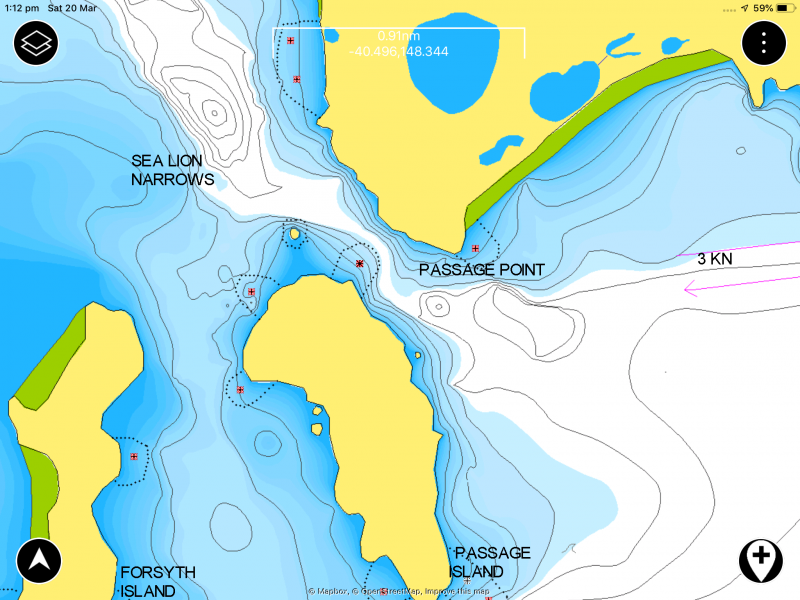

Sea Lion Narrows ~

After a peaceful night under a cold black star-filled sky, dawn brought northwest winds churning up Armstrong Passage. Needing better shelter, we flew downwind under sail with gathering storm clouds pursuing us, towards Burgess Bay, a safe anchorage on the east coast. Between us and that protection is the much-feared Sea Lion Narrows, where swift currents stand water vertical. It’s a narrow passage is further encumbered by a rock midstream at the tip of a sand spit. We’ve been both ways through it. The first time, seeking shelter from a nasty blow, bucking into the wind but assisted by a raging outgoing current that saw our full horsepower roaring with zero showing on the speedo, and yet, we raced through like a speedboat white water flooding our foredeck. Our second passage was far more benign. Current with us, like a ghost on a zephyr. Feeling like experts this time, all elements with us, we held full sail and filmed the adventure. So quick, doubled our speed. Fun!

Sea Lion Narrows

Burgess Bay ~

Burgess Bay should have been a top spot to weather a storm. Unfortunately, it sits under an old nemesis of ours, Mount Kerford, where the locals claim wind is made. Against blasts topping thirty knots, we climbed closer to the shore seeking shelter, the gently shealving sand bottom allowed us to anchor close. After tiding up, shipshape, ready to go, a cold one in hand, we fished, thinking there had to be a few flathead there. Darkness closed in, and the blasts found a new fury. At its worst, forty-six knot gusts screeched down Mount Kerford causing groans in our ground tackle, and thoughts of snapped anchor shackles in our heads. Instead of reading aloud, or watching a video, too much noise, we glued our eyes to our GPS icon blinking .03NM from our anchor. That’s the length of anchor chain.

Gale Two started to ease at bedtime, allowing us to set an anchor alarm, then settled down to fore and aft sleeping.

We were now on the east coast of Cape Barren with more westerly winds forecast, so we worked out a tour of new anchorages. The first, just five miles up the coast at Thirsty Lagoon. Visions of launching the Green Machine kayak for a leisurely paddle upon its huge enclosed waters saw us raise sail for a fast morning passage. Beaut spot. Long sandy beach, nothing manmade, but the tide was wrong barring the lagoon.

We were now on the east coast of Cape Barren with more westerly winds forecast, so we worked out a tour of new anchorages. The first, just five miles up the coast at Thirsty Lagoon. Visions of launching the Green Machine kayak for a leisurely paddle upon its huge enclosed waters saw us raise sail for a fast morning passage. Beaut spot. Long sandy beach, nothing manmade, but the tide was wrong barring the lagoon.

Just a long gentle roll rounding Harley’s Point brought a comfortable night, but we learned of a new gale in the evening forecast, the third in a week. Next morning we launched the Green Machine to look at the lagoon entry, but thought better of trying to challenge the breakers. Instead, we paddled towards the rocky point where a quiet landing spot invited us to beach comb for an hour while the tide rose.

Meanwhile, a cray-boat came in, so we stopped by on our way to the lagoon entrance, meeting Tony and his deckie Marvin. Crazy, we knew Tony’s brother, and years earlier, we’d shared an anchorage with Tony and his brother at Babel. For an hour, we drifted alongside, exchanging news and views, and heard how Tony and his sons had dug a channel to open up the lagoon about a decade earlier. Before that, it was a mosquito infested entrapped waterway. Asking his advice on the coming blow, Tony suggested the next bay along. And with that, we shoved off to brave the small breakers into the lagoon. Oops, once inside we realised we’d forgot about the speed of the incoming tide filling the lagoon and had to paddle like Olympians to get out again.

Gale Number Three ~

Maybe we were getting hardened to all the noisy buffeting wind because after shifting to the new spot fronted by low land, we managed easily. Lying in bed, the anchor alarm set, watching a movie with the sound up high.

Farsund ~

In 1912, Captain A.E. Abrahamsen of the Farsund, a three masted steel-hulled barque of 1,351 tons, made the fatal mistake of running aground on the worst sandbanks in the Furneaux Group of Bass Strait Islands. Franklin Sound separates Cape Barren Island from the larger main island, Flinders, its eastern entrance has the descriptive name of Pot Boil. Fast currents run through shifting sandbanks, reaching six miles offshore. We’ve been through them a few times, and some grey hairs show for the drama. But the Farsund must not have known about them, and has lain in shallow water for over a hundred years, a rusting steel hulk, home to hundreds of smelly cormorants. During the calm after the storm, we decide to pay her a visit.

Getting to within paddling distance in Banyandah was scary, but with modern navigation gear we found a spot a half mile away in five metres with the tide rushing past going north, towards the Farsund. The outward journey went okay except for a few breakers over shoals that put us on high alert. But we made it, holding our breaths. Jude shot some awesome footage while I kept us from joining the seabirds lining the deck. Then we thought, why push our luck, and started for home. Paddling up wind against the current, an occasional breaker sweeping through kept us focussed on our task. The Creator must smile on fools like us, because we got back without swamping the Green Machine. Here’s a video of the action.

Next came an even more daunting task. We could go seaward and north to the entrance to Pot Boil and brave its overfalls once again, but there’s another channel inshore, along Vansittart Island. To reach it meant dodging a maze of shallow sand spits and breaking high spots. We tried once years ago and had to turn back. Fortunately, the day was quiet and Tony had kindly given us a few of his waypoints. After entering them into our chart plotter, we set off with fast beating hearts. The entire operation planned around the wind and tides. We’d sailed to the Farsund at the beginning of the rising tide and carried on with it, adding more depth and more speed to our craft. Perfect as clockwork, nary a new grey hair. We came into the small port of Lady Barron with the last of the rising tide and took up a MAST mooring.

Lady Barron ~

Settled in the sheltering hands of surrounding green hills is Lady Barron, the only port for the Furneaux Islands. It has one jetty that the Matthew Flinders, the twice weekly barge, disgorges its cargo of anything from cars to sacks of potatoes, even a passenger or two. There must be trouble in the fishing industry because we didn’t see any fishing boats and heard there are none around. Instead of them lining the jetty, a ghost ship hung there with tattered sails fluttering in the afternoon breeze. It seems a lone sailor set off from Eden, and no one ever heard from him again.

Settled in the sheltering hands of surrounding green hills is Lady Barron, the only port for the Furneaux Islands. It has one jetty that the Matthew Flinders, the twice weekly barge, disgorges its cargo of anything from cars to sacks of potatoes, even a passenger or two. There must be trouble in the fishing industry because we didn’t see any fishing boats and heard there are none around. Instead of them lining the jetty, a ghost ship hung there with tattered sails fluttering in the afternoon breeze. It seems a lone sailor set off from Eden, and no one ever heard from him again.

A long weekend holiday created a deserted town, so we strolled the few empty streets alone, had a coffee at the only store, then enjoyed what every sailor loves, a hot shower with plenty of freshwater, compliments of the community. With good phone coverage, we spoke with the family for hours, told them our stories, sent off heaps of photos, washed some clothes and enjoyed another hot shower.

But the meteorologist forecast another blow for mid-week. Lady Barron is not to our liking during west winds, so we mosied off to check a couple of new anchorages that looked fine for protection. That was a mistake!

Travelling east through Franklin Sound, tide assisted, the westerly arrived early. When the first anchorage didn’t appeal, we had to power against the wind to reach the second at Munro Bay on the north side of Cape Barren Island, finding it a magnificent setting. Beyond the sound dotted with islands, the jagged Strzelecki Peaks erupted from Flinders Island, while nearer to us, bald rock Devils Peak and Double Mountain kept us company.

Storms begin easy. All night a gentle breeze held us steady to the shore, and we relaxed, thinking our Manson Boss had pierced the thick ribbon grass carpeting the bay. When grey light brought the heavy guns, lying in bed, Banyandah sheared off and we held our breath until she pulled back in line with the wind. We had company in this bay, a yacht anchored in the prime position. Over the next half-hour, the gusts got more savage until we noticed it dragging. When a boat falls off with a wind gust and never pulls back straight to its anchor, she’s dragging her anchor through the weeds gathering a crop, a weedy ribbon, hundreds of them. They can clog an anchor. We watched the vessel drag abeam of us with no one on deck and gave them a loud shout. Up popped a man, who immediately ducked below to reappear with a lady, both in wind cheaters. While we sat comfy in the lee of our dodger, they started engines, but, instead of resetting their anchor, they motored off toward Lady Barron, leaving us quite alone in strengthening wind gusts.

Munro Bay, Franklin Sound

Munro Bay is not what we’d class a storm anchorage. Beautiful views, isolated, inviting rock outcrops to explore by kayak, but it’s very shallow for a long way out and full of ribbon grass. As the day progressed, so did the storm. Bigger blasts created bigger seas, but we held–until after lunch when Banyandah did not pull back straight, but stayed heeled over, the wind on her side. Not quite battle stations! With nothing behind us, at first we watched her dragging, hoping the BOSS would get a grip of something. But it didn’t. The further we blew out, the bigger the sea, and the faster we dragged until I decided to reset. Now, setting an anchor in 30 knots of wind is far more difficult than in a breeze. Just getting the head of the ship up into the wind takes heaps of power, demanding excellent helming and coordination between the anchor man and helmsperson. Voice commands are blown away, so we use hand signals. We have our own set. I point where to go, above my head so Judith can see. Faster is a hand motion forward. Slow down – patting down, anchor off the bottom—finger up, anchor in the rollers—thumb up, are a few we use.

We got back to our original spot and thought we’d try closer and be covered by the rocks off the point. As soon as Jude took the revs off the engine, we sheared off as the anchor went down. No stopping now, I let out chain until most of it was out then let it take the strain and released more, hoping to dig the anchor in without ripping it out. Ribbon grass is the hardest to penetrate. Its roots are thick and interwoven; its strands are long flat tough stuff that clings. We held for a minute or two, giving us hope, then blast, we were off again.

We tried on the other side of a shallow area to see if we could get closer in, to help ease the strain. But ended up uncomfortably close to rocks we’d hit if the anchor let go. So we held a brief conference. Jude suggested going further out into deeper water where ribbon grass may not grow. The seas would be bigger, but if we could find sand bottom that wouldn’t matter to the BOSS. So we drifted downwind into around 15 metres of water and did our thing of setting our anchor in blustery rocky-rolly conditions.

Now this might sound strange, but anchoring in deeper water has advantages. Imagine the weight of all that chain sloping down, acting as a buffer. The catenary smooths out the jerk from windblasts. In shallow water, the chain lies on the bottom and the pull is direct. In this case, it worked magnificently. Although the wind swell was more powerful, we held bow straight into them and with the anchor in sand; she held through worse conditions that came.

But, we’d had our fill of gritting our teeth and hanging on. Next day, in calm conditions, just a light north breeze, we sailed around the corner to Thunder and Lightning Bay, to get ready for a journey south out of the Furneaux Islands.

Passage South ~

In these latitudes, a big part of managing a sailing ship is planning to the weather. Jude and I spend a lot of time keeping abreast of changes. Today is so different from decades ago when we tapped the barometer and looked at the clouds. How blessed are we for having that grounding. Earth is a magical set of systems, interdependent on each other.

In these latitudes, a big part of managing a sailing ship is planning to the weather. Jude and I spend a lot of time keeping abreast of changes. Today is so different from decades ago when we tapped the barometer and looked at the clouds. How blessed are we for having that grounding. Earth is a magical set of systems, interdependent on each other.

While in port, we had watched several systems come and go, and now saw a narrow opportunity to sail south, not just another island hop, but a long way down Tasmania’s East Coast. An obstacle we had to consider is Banks Strait. It’s unwise to buck its fast currents, or wind against tide that sets up horrible seas, making life miserable. An early start would be required. That left time for a walk on the shore to explore Key Island Bay and see again the inconic Preservation and Rum Islands.

Early hours are often windless so we had to motor most of the twenty miles through Banks Strait, assisted by the tide. But that was soon forgotten silent under sails heading offshore to keep the wind. Throughout the night, with no other lights, we gazed upon every star while Banyandah slid silently along under the guiding Southern Cross. Heavenly.

First sunburst breaking the flat horizon found us ten miles short of Wineglass Bay, behind schedule beggars decisions. Should we head for Schouten Island or believe the forecast of increasing winds and run the remaining forty miles to Orford? It’s a magnificent life experience to make these decisions, to balance forecasts with likely outcomes and decide a course. Then bear the consequences. We’re simple folk, hurt no one, and live on the edge in harmony with Earth. What a fantastic life.

Fortunately, this story has a Hollywood ending. The on and off wind found a rthym and we decided to carry on. Calculating we’d just squeak in with last light, and thinking it a clear anchorage, can be done in darkness. But, that magical wind got stronger and stronger till at lunch, Too much sail, leaning over, hanging on dodging water spray, racing towards our destination.

After thirty hours of rocky-rolly life, Banyandah stormed into Prosser Bay, Jude at the helm, bulging muscles mastering the wheel through wavelets into the tranquil sound backed by forested hills. Gee, the yellow grass hillsides reminded us we were now two-thirds around the wonderful island of Tasmania. They also reminded us that getting back to Strahan, the hardest miles are yet to come.

Till Next Time, Stay Safe.

J&J