In a dawn thick with cotton-wool mist that seemed to suck in all sound and mute the throb of our six-cylinder engine, we started our journey into the distant past by first negotiating the shallows off Carver Point. Somewhere through that wet mist, remnants of Carver’s shipyard lay hidden amongst thick mosses and logs fallen these many years since the Lady Franklin first slid into the waters of Port Davey, perhaps the last vessel hewn from local stands of Huon.

In a dawn thick with cotton-wool mist that seemed to suck in all sound and mute the throb of our six-cylinder engine, we started our journey into the distant past by first negotiating the shallows off Carver Point. Somewhere through that wet mist, remnants of Carver’s shipyard lay hidden amongst thick mosses and logs fallen these many years since the Lady Franklin first slid into the waters of Port Davey, perhaps the last vessel hewn from local stands of Huon.

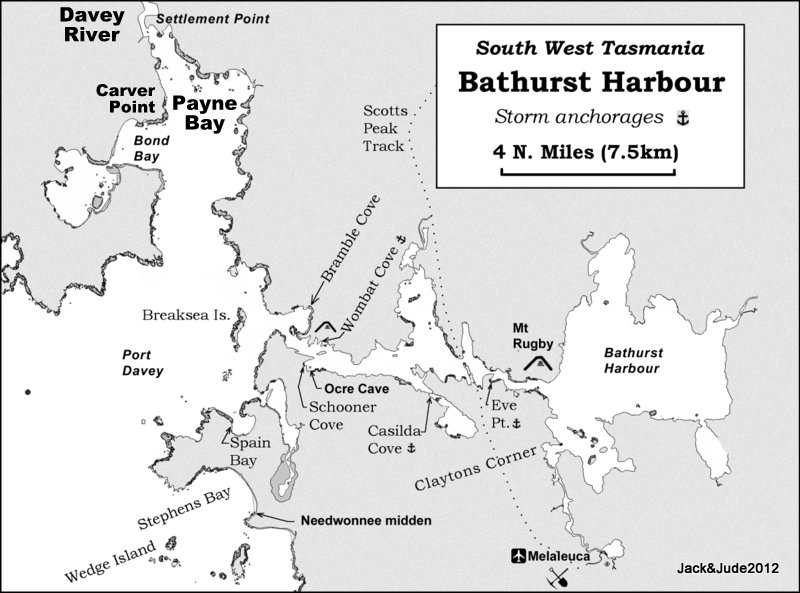

Up into Payne Bay filled with nasty sharp rocks we navigated to a spot off the unseen Davey River Bar. In shallows that left only half a metre under our keel, we set the hook into something that sharply pulled our lady around to the sun bursting through, clearing the day to become one filled with endless blue above rolling hillsides of tawny buttongrass spotted by grey-white dolerite rocks, craggy and menacing. This was not a place to relax when leaving your craft.

Back in 1871, when travelling with a party including Mr. Piguenit of the Lands Department and Frank McPartland who was a top bushman on official business as constable from Picton; a Mr. James Scott noted at the northern extremity of Payne’s Bay, settlements on both sides of the Davey River. He wrote in the Mercury that a “Mr. Docherty the oldest resident, and a Mr. Carver with ship-building yards, and others, resided on the west side.” And that, “a Mr. Woolley and several families engaged in the pine trade lived on the east side. The population amounted, altogether including children in arms, to about 40.”

He writes of a township with houses “To Let,” but they encamped in what “once had been a garden, now a wilderness of ferns and strawberry plants, with a few apple trees and currant bushes. The tall tea tree along the beach has been left growing, and forms a good breakwind against southerly weather for the row of houses which are built behind it.”

He also told the people of Hobart in 1871, “Mr. Carver has a 60 ton schooner nearly ready to launch, built of the Huon Pine obtained up the river. The piners have to go some 15 or 20 miles up the Davey River to the timber beds… felling the trees in the summer months, branding the logs, and placing them in the water so that the first flood may float them down, where they are caught and fitted for market.”

Today the Port Davey Marine Reserve in the southwest of Tasmania is located within the boundaries of the Southwest National Park and the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Originally proclaimed in 1951, the Southwest National Park is classified as IUCN Category II – National Park, and is fully protected under the National Parks and Reserves Management Act 2002. The Port Davey Marine Reserve was proclaimed in 2005.

Whalers, sealers and piners (timber-cutters) first arrived in the early 1800s. Bay whaling stations were located at Bramble Cove and Turnbull Island. Pining villages were located near the mouth of the Davey River at Piners Point and Settlement Point, and another at Spring River. By 1890, with both whales and Huon pine nearly exhausted, Port Davey was largely abandoned.

Since the 1900s the area has seen only three long-term resident families: the Claytons, Kings and Willsons.

The Port Davey landscape could be mistaken for a glacial fjord, but is in fact a drowned valley or ria. Bathurst Harbour was once a large plain that flooded as the sea level rose about 7000 years ago with late melting of the last ice age. The geology of the area is largely billion year old quartzite’s, originating as sand and mud laid down in shallow seas, which over time were metamorphosed by heat and pressure into quartzites and schists, then uplifted, folded and partially eroded away. Younger conglomerates are also present.

The soils that cover much of south-west Tasmania are organosols – loosely referred to as peat. Organosols form from undecomposed plant material that slowly accumulates under extremely wet, humid and cool conditions.

But we had not come just to witness peaty soils and the few piner remains. Our main focus were the ancient rocks forming the Davey River Gorge, renown for their reflective beauty during calm weather.

While preparing the Green Machine for a paddle to Settlement Point, then as far up river as we could get, the boys off Melian, nearby in the western anchorage, dinghied over to ask if we’d like a tow up river. Our big smiles signalled ‘you bet.’

Scooting along easily in tow, we in fact overran their tinny at times while surging forward on mini-swells crossing the bar. But once past those into smooth water, our Green Machine behaved herself. We passed Settlement Point behind a lovely sand-spit with views south to Mount Perry and the other lofty mountains surrounding Port Davey. And while gliding over the water without any effort we imagined winter storms rolling big swells up the bay that foamed white on that spit. The river then widened to buttongrass slopes with patches of forest that simply sparkled on this cloudless day. Our tow pulled us past shores that a hundred fifty years ago would have had logjams of Huon rafted along it, where today small families of swans live in serene surroundings nibbling grass out the dark water.

After an hour and a half, rounding a corner exposed a gash through a mountain of white granite. The river had also narrowed increasing its flow so we threw off the tow. And for the first time could enjoy the spectacular scenery in silence and suddenly heard our world filled with a chorus of birds celebrating the beautiful clear morning. Leaving the three boys to themselves, Jude and I paddled slowly up through the gorge sucking in the wonder of it all. After a far bend another river entered with a shale bed of white rapids ahead. Stroking faster, in cadence, we entered this fast water and made headway almost to the smooth water above. But with only a kayak length distance to go, paddles hitting rocks brought our forward motion to nought, and by a look sideways at a huge log, we’d never make it past the rapids, no matter how fast we stroked. Within view of the second gorge we started drifting back through the first to get a double helping.

What a heavenly experience. Golden yellow reflecting off the underside of rock was mirrored on the black river in striking contrast to the white rock. Apart from several Richard Taubers serenading us, and the occasional swirling water, it was absolute silence. Several times we retraced our course back upstream to drift again to replay an especially lovely section. And twice we moored alongside the cutest rock outcrop thickly coated in green and adorned by two bonsai trees. Our slow movement immensely enhanced the video quality, and while our cameras recorded Nature’s majesty, we fantasized the scenery was our back garden.

Mr. James Scott observed in 1871, “The grandest bit of scenery is ‘Hell’s Gates,’ and the falls on the Davey River, a pull up from the settlement of about 5 miles. The gates are a tremendous chasm rent between two hills, about 40 feet wide, and with perpendicular sides 250 feet high that extend about a furlong in length, through which the Davey River has forced its way. In a flood, the water boils and seethes in a fearful manner, so that it would be impossible to venture near in a boat.”

We sped downstream amazingly fast until a breeze across the wider stretches had us pulling a bit harder. The forecast NE wind came instead from the south, an onshore afternoon sea breeze that we should have expected on such a cloudless hot day. But it didn’t stop Jude and I completing the 9 km paddle to Settlement Point in one and a half hours. That kayak is fast.

Exploring Settlement Point was another treat. We found the old sawpit reported last used in 1870, and strolled through the glen that today is what’s left of the settlement. A wonderful afternoon to shoot video and record the story of yesteryear.

With the afternoon seabreeze gaining strength, we spotted breakers on the Davey River Bar. But our paddle out the river and into the breeze wasn’t really so hard, Banyandah was in sight, even Little Red could be seen bobbing in the ruffled water now totally exposed to a long fetch. The 2 km journey took 20 minutes and we were relieved to see our lady still firmly attached to the bottom, even though she now faced the exact opposite direction.

After loading GM and clearing the decks, we sat peacefully observing the wonderful scenery while our muscles tingled, Jude gushing how great she felt. But a windstorm was coming that would end this bout of clear weather so, reluctantly we began an easy two-hour motor back to the safety of Bathurst Harbour to spend the night in Schooner Cove under a star filled still night, the calm before the coming storm.

I love your blogs and all the photos. Your writing has inspired me but I have no sailboat. I sailed on the Bomoh a 53′ Ketch around Tasmania, as cook. I am a boat hopper you might say-:) lol … I loved Port Davey but the time went too fast for me. Oh how I would love to sail again with someone who has done the voyage before as they seem to learn from the past sail and if returning, they must of loved the place. Maybe I should start a blog as I go to Alaska 4 years in a row now but not the last 2 years. I am going back, hopefully to try to sail part of or all of is my dream, as I read ‘Passage to Juneau’. I learnt so much but want to do the same and more. Have you got sailing in your blood like I have. Well I am mainly land based until I sell my home and then I am off like a gypsy, going to see as much as I can in the short part left of my life. It ujis a big world. Thanks again, I want to know more about all your travels…what a life!.

Hi Sarah, I just emailed regarding your Video stick, and I’ll organise an electronic copy of Two’s a Crew for you. But a word of caution, life afloat is not for everyone. And selling a house to buy a boat before knowing all the cons can lead to complications, on the other hand, if the glove fits wear it. Maybe your idea of sailing a season on someone’s else craft will make that decision easier.