In February 2012, Jack and Jude made a two-week journey up the Gordon aboard Banyandah to Sir John Falls, then a further 12 km upstream to the “Rocky” Sprent River in the Green Machine kayak in search of Huon Piners remnants from the early 1900s.

Pining in the Gordon River area was carried out between 1816 to the late 1930s. Two or three man teams worked four-month stints, leaving after Christmas, returning to Strahan for Easter, then rowing back up the mighty Gordon River at the start of winter to work in snow and ice harvesting logs ready for the summer thaw that would flood them down river.

Families such as the Abels, Doherty, Cranes and Morrisons had several generations of men working on the banks of the Gordon River and its tributaries harvesting the trees with axe and crosscut saw, and then moving them into the rivers using just block and tackle, and lots of muscle.

It was not always carried out at the same intensity, pining had its peaks and collapse periods, and material evidence of these activities is generally in very poor condition due to the harsh nature of the environment and the fast speed at which the flora regenerates and covers everything, as well as the temporary nature of the original huts and camps.

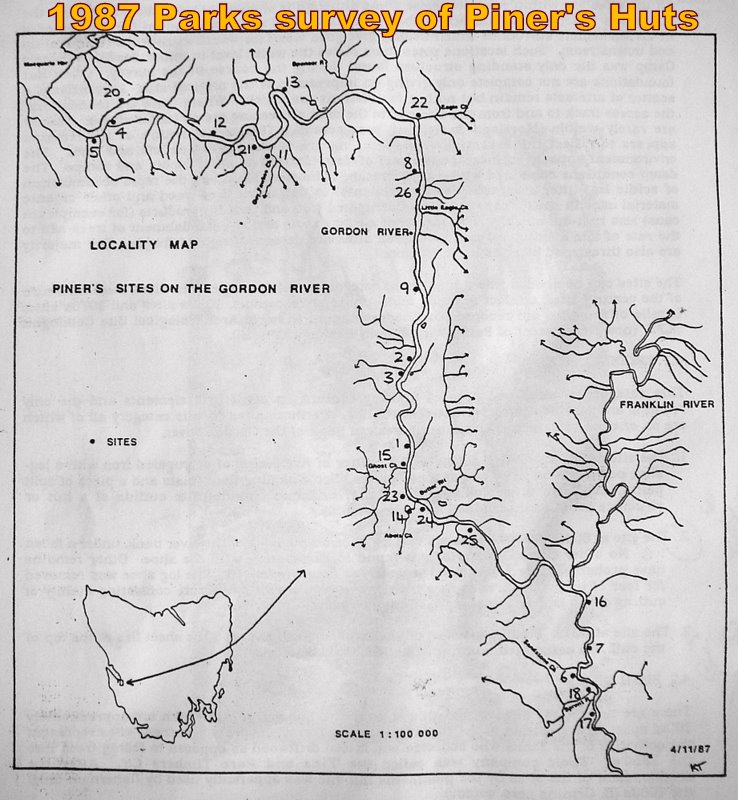

The only survey conducted was by National Parks in 1987, pre-GPS, with site locations recorded to within 100 metres on a topo-map. Many times we were to find their data in error by considerably more than 100 metres.

The only survey conducted was by National Parks in 1987, pre-GPS, with site locations recorded to within 100 metres on a topo-map. Many times we were to find their data in error by considerably more than 100 metres.

Our expedition, privately funded and organized, was to record what still remains today, with an exact GPS location of our findings.

Cruising per se can be fun and adventurous, but when boat-handling skills are applied to achieve a goal, the fun is magnified by a lasting reward. During the late 80s and 90s, in-between our long lay-off from the sea, Jack and Jude turned to wilderness walking to get their Nature fix, and we gained additional survival skills and the ability to track through difficult terrain. At one time we worked with Parks to help document lost mining sites deep inside World Heritage forests and it was those experiences that helped us in the thick Gordon River “horizontal” rain forest where leeches and ticks thrive and deadly snakes lay hidden.

Our first goal, to “find” a relatively easy target, Duncan’s hut, built in the 50s by fishermen. We needed to compare our GPS with the survey’s recorded position to determine which co-ordinate system had been used by the surveyor. There are several and the report did not specify which system had been used. Two miles into the Gordon, we found Duncan’s hut easily in a clearing surrounded by a tangle of saplings, leaning over at an alarming angle. Examining its rotting innards, we concluded it would collapse in years not decades. Its famous dunny was also found, flattened under a fallen blackwood tree. Comparing the data, we had a 150 m discrepancy no matter which mapping system was selected.

Our first goal, to “find” a relatively easy target, Duncan’s hut, built in the 50s by fishermen. We needed to compare our GPS with the survey’s recorded position to determine which co-ordinate system had been used by the surveyor. There are several and the report did not specify which system had been used. Two miles into the Gordon, we found Duncan’s hut easily in a clearing surrounded by a tangle of saplings, leaning over at an alarming angle. Examining its rotting innards, we concluded it would collapse in years not decades. Its famous dunny was also found, flattened under a fallen blackwood tree. Comparing the data, we had a 150 m discrepancy no matter which mapping system was selected.

Out next easy target was not a remnant from the Piners’ past, but dates further back to the Sarah Island Penal colony of 1823, when lime was extracted from the cliffs along the Gordon River then burnt for use in mortar and fertilizers. Convicts built and used a limekiln that still survives today and to find it we used the stated position from the survey as a starting point. It provided several hours of pushing through thick-forested hillsides draped in lush green mosses, but no kiln. Thinking laterally, remembering what a local had said about the kiln being just after the third lime cliff, we paddled 500 metres downstream and landed basically right on the limekiln’s doorstep. During these searches we visualized the hut, or in this case the kiln, in its working state to better figure where it would have been sited. The huts often had views along the river with easy access from shore and the kiln also needed a loading flat, neither often found along this abrupt shoreline. At the same time, keeping in mind both the Piners and convicts would have flattened the forests, often clearing an area by burning.

The limekiln certainly is impressive. Constructed from red bricks made on Sarah Island in the early 1820s, it is domed, about 2 metres in diameter, and stands a metre out a thickly leaf mulched hillside. The original posts used as lintels are still holding up the bricks surrounding its entry. Its position being even further away from its reported spot was the second indicator of the 1987 survey imprecision.

The limekiln certainly is impressive. Constructed from red bricks made on Sarah Island in the early 1820s, it is domed, about 2 metres in diameter, and stands a metre out a thickly leaf mulched hillside. The original posts used as lintels are still holding up the bricks surrounding its entry. Its position being even further away from its reported spot was the second indicator of the 1987 survey imprecision.

Next we looked for two bottle caches, finding one in a lovely leafy mulched knoll on Limekiln Reach in the shade of numerous man ferns, Dicksonia antarctica, also known as the Soft Tree Fern or Tasmanian Tree Fern. They can grow up to 15 m but these were typically about 5 m. Consisting of an erect rhizome forming a trunk that is very hairy at the base, with large, dark green, roughly-textured fronds spreading in a canopy up to 6 m in diameter. The trunk is merely the decaying remains of earlier growth and forms a medium through which the roots grow, but will not regenerate since it is dead organic matter.

The bottles, found nestled in the decaying bole of a fallen tree lying across a small stream, when excavated from thick moss proved to be mostly green champagne bottles with one H & P sauce bottle and another of an unknown type. Picking up one of the champagne bottles while gazing through the shady landscape to an expanse of river, it was easy to imagine a picnic spread upon that gentle slope. For many decades, holiday excursions up the Gordon have been a favourite.

The bottles, found nestled in the decaying bole of a fallen tree lying across a small stream, when excavated from thick moss proved to be mostly green champagne bottles with one H & P sauce bottle and another of an unknown type. Picking up one of the champagne bottles while gazing through the shady landscape to an expanse of river, it was easy to imagine a picnic spread upon that gentle slope. For many decades, holiday excursions up the Gordon have been a favourite.

Near Butler Island, a rock splinter rising mid-river between two cliff-faces, there had been several Piners’ camps and one used by the HEC. Just downstream, Abel Creek provided access to the hinterland with a track crossing button grass plains to Gould’s Landing above Sir John Falls. From there it carried on up to the Sprent. In olden days, supplies were taken in on this track. Later, teams of draught horses laboured along it dragging Huon logs down from inland stands. Today, Abel Creek has regrowth of saplings and thick “horizontal” Anodopetalum biglandulosum, a small tree endemic to western Tasmania. As it grows, the trunk bends over under its own weight and ends up parallel with the ground. Vertical branches grow from these and bend over in time; hence the tree becomes a tangled mass of branches that is nearly impenetrable. We made two exhaustive searches for camp remnants in Abel’s, spending the better part of two days slogging in bog, picking off leaches, fighting through regrowth. And what we found was nothing more than a patch of flat ground that may have been the campsite.

Further downriver we had better luck at what had once been the Ghost Creek camp, locating a lone bedpost rising out a carpet of moss. What a beautiful image! Situated on a high bank, the bed runner, now a mound of moss, led the eyes towards a fine view of the mighty Gordon. Next to this tiny relic, a half sheet of corrugated iron lay nearly covered in green.

On the upstream side of Butler Island, the HEC had drilled into the bedrock, testing for as a possible dam site. Searching their camp area revealed a few rusting steel drilling pipes and several rotten joists from their temporary hut.

On the upstream side of Butler Island, the HEC had drilled into the bedrock, testing for as a possible dam site. Searching their camp area revealed a few rusting steel drilling pipes and several rotten joists from their temporary hut.

Further round a few river bends is the site of the 1982 protest against the Franklin below Gordon Dam that took place at the HEC work area at Warners Landing. The jetty can still be used although some iron pokes out the large logs. The boggy wet track from it leads up to a clearing with abandon equipment. Thirty years ago, that track continued on through forest to the proposed dam site. Across the large body of water is Sir John Falls, where above them had been the residence of a forestry manager whose job was to count Huon logs floating down river in order to collect the correct levy. The house was shifted years ago, but the foundations and some steelwork remains.

Further round a few river bends is the site of the 1982 protest against the Franklin below Gordon Dam that took place at the HEC work area at Warners Landing. The jetty can still be used although some iron pokes out the large logs. The boggy wet track from it leads up to a clearing with abandon equipment. Thirty years ago, that track continued on through forest to the proposed dam site. Across the large body of water is Sir John Falls, where above them had been the residence of a forestry manager whose job was to count Huon logs floating down river in order to collect the correct levy. The house was shifted years ago, but the foundations and some steelwork remains.

We secured Banyandah to Warners Landing, upstream of the motor vessel Opal Lady, and when they departed, we moved forward for a more secure grip on the landing as we planned to leave our lady there for several days while kayaking upriver to the Sprent River in search of three more camps. Late that night, while Jude packed, a possum came on board, – looks like we’ll have to shut up the boat.

Tell you how that went next time.