Jack and Jude, The Tujays, have feasted on the wonders of Tasmania for a long hot summer, but now that the Equinox has passed, a season of diving remote Coral Sea reefs tickles our fancy. Bringing the problem of how to voyage from forty-south to the tropics quickly.

Autumn brought changeable weather. Neither high-pressure cells nor depressions stay for long and they pass in latitudes that when favourable winds blow in Tasmania, headwinds prevail just north across Bass Strait. Of course the journey up Australia’s East Coast can be tackled piecemeal, in dayhops and overnighters. But the Tujays don’t have months or even weeks to nibble away at the distance and prefer to tackle Nature in one blow. Besides, other factors are involved. The East Coast suffers from a feisty south setting current, shipping abounds, and many anchorages are not available without first crossing swell swept river entries. For us, piecemeal is simply too much work to transit the more than 800 nautical miles. On the other hand, running through 12 degrees of latitude requires much luck, mitigated of course by skill and patience, a sailor’s best friends.

FURNEAUX GROUP

Situated off the NE tip of Tasmania and jutting out in to the Roaring Forties of Bass Strait is the Furneaux Group of islands, sighted by Tobias Furneaux in March of 1773. First recorded as being uninhabited, today only few Straitsmen remain on the fifty-two islands that are filled with mountains and plains, lagoons and grasslands, all abundant with wildlife. Granite rock prevails, worn smooth by time, and often artistically brushed with beautiful red lichen, a photographers dream in the ever-changing atmospherics.

Situated off the NE tip of Tasmania and jutting out in to the Roaring Forties of Bass Strait is the Furneaux Group of islands, sighted by Tobias Furneaux in March of 1773. First recorded as being uninhabited, today only few Straitsmen remain on the fifty-two islands that are filled with mountains and plains, lagoons and grasslands, all abundant with wildlife. Granite rock prevails, worn smooth by time, and often artistically brushed with beautiful red lichen, a photographers dream in the ever-changing atmospherics.

Aboard our home on the water we first explored this wild kingdom in 2010, so we had favourite spots, like Trousers Point, that wide smile of yellow sand bounding a translucent bay under the towering power of the Strzelecki Mountains. This year we tackled its tallest peak and bush bashed a few of the minor ones.

EAST COAST OF FLINDERS

After a small last shop in Lady Barron, our journey north began with a white-knuckle blast through the raging turbid green waters of Pot Boil passage, the only navigational guide rather forlorn atop Vinegar Hill five miles behind. Thankfully its high intensity sectored light shows red when too far south of the safe line, green when too far north, and steady white when transiting the safe water that is turbulent with fast currents. A frightening prospect for the novice.

East Coast Flinders is wide open to New Zealand. In contrast to its west coast, the east is flat land with a few gravel tracks around the numerous lagoons that are surrounded by a variety of vegetation including the succulent samphire, coastal heath, dry forest, melaleuca swamp, and grassland. In good times, these shallow depressions fill and abound with wildlife, in particular more than twenty species of birds from large black swans, cape barren geese and Australian pelicans, thousands of chestnut teal and banded stilts, and the quick, darting, tiny silver-eye with a conspicuous ring of white feathers round its eyes.

But rain has been scarce in our most southern state. Climate change has sent it heat waves while our home port of Ballina floods. Oh well, guess many more will enjoy fine swims in Tassie’s warming waters that are attracting many new marine species. Taswegians now quip they’ll soon be catching Coral Trout, and so they might because the bull kelp is mostly gone, the seals are looking for new ground, and huge numbers of sea anemone have invaded from the mainland.

BABEL ISLAND

In essence, Flinders Island’s east coast is one long sandy beach stretching unbroken for 62 km north to south, except for a protuberance called Babel Island that juts out about mid-way. Attached to Flinders by a mile long sandy strip that dries at low water, Babel is a tallish granite island of 440 ha in a tight group with two flat, treeless islands called Cat and Storehouse. It is a significant seabird breeding island containing the largest short-tailed shearwater colony in the world, plus a major little penguin colony, a large colony of crested tern and a large population of both silver and Pacific gulls.

This group offers wind protection from every direction, but as it faces a wide expanse of Tasman Sea, some swell can invade. If you can stomach a bit of motion, and don’t mind shifting anchorage with every wind change, Babel is a perfect first stop or departure point for the mainland’s east coast.

MUTTON BIRD HARVEST

We loved its harsh wilderness but were disappointed not to be able to film the sky blackened by mutton-birds returning from feeding, even though at the time they were rearing chicks. We saw flocks, but not in the numbers we’d seen near the Head of the Bight, which were themselves nowhere near the tens of millions described by Matthew Flinders in his voyage around Tasmania in 1798. Mutton-birds are shearwaters, the birds of St Peter, so named because they too walk on water.

Patsy Adam-Smith, author of There was a Ship, describes her first sight of mutton-birds in the 1950s as a vast darkness on the water. “Unlike the shadow of cloud, this patch did not move. As we watched the edges diffused, the whole black mass walked over the water, disintegrating as it went, each fragment a bird that then soared away, lost to our sight.”

Caught between the fierce riptides that scour Bass Strait, the seas around the Furneaux, confused and in turmoil, build up sand shoals beneath the seas. If we could fly like these creatures, we’d see swirls of blue, cream, and green created by Earth’s gigantic forces colliding. And we’d hear mutton-birds, when gathering at dusk to circle their roosts, complain between themselves, “not much food today, my chick will go hungry.” For man has fished these waters to their limits.

Harvested Mutton Bird Chicks. – Shearwaters lay only one egg.

The chick grows quickly, reaching twice the weight of an adult before the parents move on to warmer climates.

Up to 200,000 chicks may be removed from their burrows, killed, processed and sold by commercial operators.

Click to lodge your objection.

A BIT OF HEAVEN

For the better part of a week we experienced fine NE weather while waiting for a weather window to cross Bass Strait, and used the calm conditions to explore the islands in our Green Machine two-person kayak. Surrounding the islands floods a lovely sand bottom much favoured by flathead fish and we snatched a few dusky ones for our evening meals. During this time we shared this bit of heaven with only one other craft, a study steel cray boat registered in Launceston. On our second afternoon, while drift fishing from our tinny Little Red, a larger one sped up with a beefy fellow called Karl who asked if we ate crayfish!

Next afternoon he motored into our bay holding two reds that had tangled with an ockie and lost a few legs, and with deft finesse Karl powered his sixteen-metre great lump of a craft within reach of our boathook holding out a bucket then dropped them in.

Next afternoon he motored into our bay holding two reds that had tangled with an ockie and lost a few legs, and with deft finesse Karl powered his sixteen-metre great lump of a craft within reach of our boathook holding out a bucket then dropped them in.

Later that afternoon we returned his kindness, rowing over with a small gift and climbed aboard to inspect his fine craft, which he operates solo. Karl is third generation Tassie fisher and has strong views on the mismanagement of his industry. The rule makers are not fishermen he told us. They’re more familiar with financial pressures than the workings of Nature. Many fishermen believe the cray season should end when the females first start laying their eggs, whereas the males can still be taken to fulfil fixed quotas. Karl says this is detrimental to the industry. Every morning he fishes plenty of females carrying eggs out his pots and chucks them back into the sea. And next morning, the same hungry females are trapped again to again be flung back. He says, “It’d help the sustainability of the industry to just leave them in peace.”

Enjoying a cuppa in Karl’s spacious galley cum stateroom, while discussing these issues we kept an eye on his satellite TV displaying the weather channel. In a few days time, a frontal system would pass that we had been thinking of taking across Bass Strait, to at least get us on our way. But that system carried huge rain clouds, which meant viscous squalls and a wetting. A few days behind, another front followed. It looked far more placid and was driven by a hefty high-pressure system that just might provide southerly winds to take us up the east coast.

Those few days later, when angry clouds scudded over, two other sailing craft arrived from the south. In the early hours, when the front turned southwesterly they departed for Bass Strait. Tempted, but holding to our plan, Jude and I moved Banyandah back to Flinders to shelter. A wise decision. Sixty-knot gusts struck the strait that night.

OUR JOURNEY HOME BEGINS

Two days later, the skies again darkened with grey scudding clouds. This time we packed up our folding kayak, secured our grab bag of emergency rations, tied more emergency stuff into our tinny, and then without starting our engine, lifted our hefty modified admiralty from the sand bottom. Adrift in the lee of the islands, I muscled this great lump of sharp metal below and lashed it under the saloon floor.

Two days later, the skies again darkened with grey scudding clouds. This time we packed up our folding kayak, secured our grab bag of emergency rations, tied more emergency stuff into our tinny, and then without starting our engine, lifted our hefty modified admiralty from the sand bottom. Adrift in the lee of the islands, I muscled this great lump of sharp metal below and lashed it under the saloon floor.

Still adrift in the lee, our Mainsail from Hell was hoisted with two reefs, then Jude opened our logbook, and our journey home began.

Karl drove out from between the two little islands when he saw us setting sail and gave us a hearty bon-voyage. It’s always nice to say goodbye to someone, so we waved and shouted as the B felt the first strong winds. Always bits of doubt jump into our heads when heading out into strong winds, the sea crashing on board. But we were ready and excited to be away, so we snuggled close behind the dodger and recounted our many favourite moments while first Babel, then Flinders sank below the lumpy horizon.

CROSSING BASS STRAIT

Our voyage plan said we’d take a comfortable course no matter the direction, never taking the wind forward of the beam. With the wind in the NW at 20 knots, that meant we could not lay Green Point. But what did that matter when the wind would eventually back around to SW. Bouncing along, I braved a few outings onto the deck to rig safety lines and windvane adjustment cords. Then at dusk Jude went off to bed leaving me the solitude of a half moon rising above a dark sea.

Ready for my night watch wearing our emergency belt with PLB, strobe, whistle, MOB sensor, and harness.

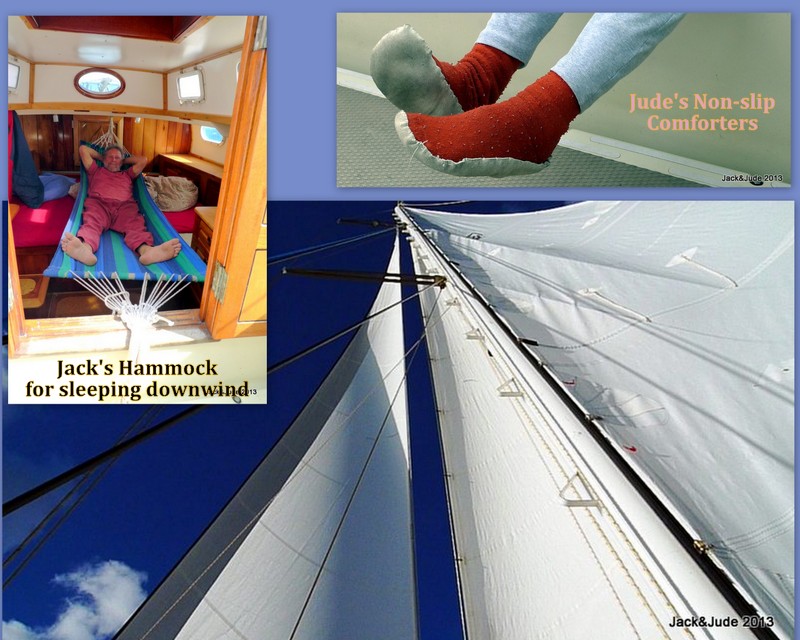

Nearer our midnight change of watch the wind increased to over 25 knots, and when I awoke Jude, together we dropped the mainsail to continue flying along under 70% headsail. Written into the logbook, Jude copped “ferocious gusts” of 35 to 40 knots, while I recorded, “a horrible night – up/down, slip sliding, no sleep, sat upright 1/2 the night.” My injured right shoulder not liking the hard work and violent motion.

A rainsquall next morning at 1100 swung the wind to SW, so we raised the staysail, poling it out to SB, at the same time poling the headsail out to Port, then we ran wing and wing. Any sailing vessel crossing Bass Strait with that configuration is going to roll violently and all we could do was hunker down, try not to get hurt, and grin and bear it.

A rainsquall next morning at 1100 swung the wind to SW, so we raised the staysail, poling it out to SB, at the same time poling the headsail out to Port, then we ran wing and wing. Any sailing vessel crossing Bass Strait with that configuration is going to roll violently and all we could do was hunker down, try not to get hurt, and grin and bear it.

After 36 hours the SW moderated to just a few rain showers at 20 knots, and we were almost across the strait having logged nearly 200 miles with the seas running even at 3 to 4 metres. From there, it just got better and better. Jude slept on the saloon floor our second night. Then after midnight, I tried sleeping aft and got a few winks.

At dawn our third day, Jude crashed aft, sleeping soundly as the wind abated to a moderate breeze. An hour later it had dropped further, no longer making whitecaps. By noon we were adrift.

ADRIFT

Dolphins cruised by on the rolling seas, a Portuguese Man O’ War floated past, and then a Wandering Albatross landed to paddle right up to our boat. Grabbing the video to film Jude feeding it the remains of our last flathead, I was astounded to record how disgustingly dirty the sea was, with massive particles of debris looking like half-digested human excreta.

Dolphins cruised by on the rolling seas, a Portuguese Man O’ War floated past, and then a Wandering Albatross landed to paddle right up to our boat. Grabbing the video to film Jude feeding it the remains of our last flathead, I was astounded to record how disgustingly dirty the sea was, with massive particles of debris looking like half-digested human excreta.

We drifted all that day, and all our third night at sea while it got calmer. Jude recorded at midnight, “No canvas spread. All down since 1745 yesterday. Less than one mile drift in 12 hours. Eating fried eggs on toast – the last two slices of bread, and hearing birds calling. Amazingly beautiful out here, even in the light drizzle.”

The barometer, which had fallen our second day to 1010 mb, had now risen to 1019; while the sea temperature skyrocketed from 20 to 26 Centigrade.

At the beginning of day four, patchy cloud in a blue sky brought a hint of breeze that grew stronger with every puff. Coming first from the east, then SE, switching every which way until settling back in SW at 15 to 18 knots. By noon, we had made good 290 NM from Flinders, with about twice that distance yet to go to our family and impish grandchildren, and were was sailing NNE, 120 NM off Bermagui on the NSW coast.

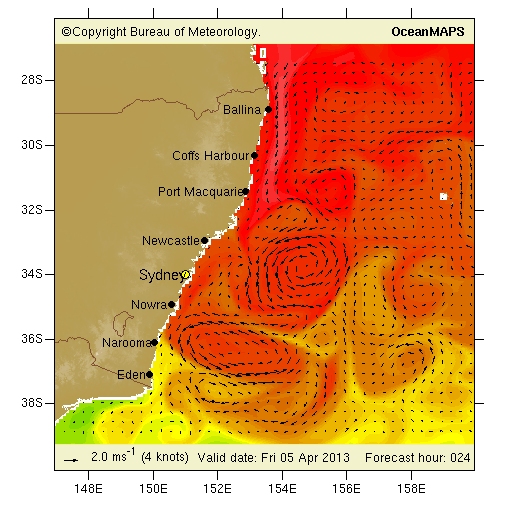

EAST AUSTRALIAN CURRENT

Prior to setting sail, knowing we’d probably be out of internet range, I had recorded weather images for a full seven days from the BOM marine weather site. The bureau also provides images predicting the East Australian Current direction and speed for seven days, and using this information, I was directing my ship towards the first of several counter currents that flow north. These current charts show that the fast flowing EAC is actually a number of swirling eddies. Near the coast they run south at up to 4 knots, easily half the speed of our ship, while well out to sea, there are counter flows and it was our intention to use these.

Prior to setting sail, knowing we’d probably be out of internet range, I had recorded weather images for a full seven days from the BOM marine weather site. The bureau also provides images predicting the East Australian Current direction and speed for seven days, and using this information, I was directing my ship towards the first of several counter currents that flow north. These current charts show that the fast flowing EAC is actually a number of swirling eddies. Near the coast they run south at up to 4 knots, easily half the speed of our ship, while well out to sea, there are counter flows and it was our intention to use these.

At 1900 Jude was in bed while I was eating flathead fish cakes for dinner with the same two reefs in the mainsail, the headsail poled to weather, the staysail sheeted home, Banyandah flying north at 8 knots.

A long sea voyage, especially one with no outside contact, becomes a world of its own. Jude and I cherish these times surrounded by pure Nature. Sure, it’s not the most comfortable, and maybe we don’t get as much rest as we’d like, but far beyond those inconveniences we share unique moments that are treasured forever. Together we face the hardships, and together we conquer them, adding immense strength and understanding to our bonds. We marvel at the beauty of Earth, her night sky so alive, her daylight bright with other creatures gliding along looking for sustenance or hip hopping atop blue waves plucking tiny morsels. Humbled by these experiences we are constantly reminded that we do not inherit the Earth from our Ancestors – we borrow it from our children.

NSW has some of the nation’s poorest marine facilities even though we pay more through fees than anyone else. This is causing our historical sea villages to become less relevant as the old codgers die off, the youth not attracted to the sea. That’s a real pity because the sea is the greatest leveller of mankind. It firmly fixes our heels to Earth and builds good character. We say, get the kids into real life thrills and away from computer screens, fill their lungs with pure sweet air instead of drugs, and give them some spine to stand tall amongst the difficulties of real life that hasn’t a reset button.

NSW MOST DANGEROUS RIVER BAR

The Ballina river bar at our home port is the most dangerous on the coast because it has not been dredged for twenty years. A lack of money, a lack of will has seen this once proud ship building port that was well maintained when the world needed our timber and sugar, now become a risk of life to enter. It is so dangerous that I had set our course for the Clarence River 35 NM south of Ballina with the thought that we’d stop there until perfect conditions could be predicted to enter our own river.

For six days and nights we sailed with the same high-pressure system slowly backing round to the east. This we used to close with the coast, and as if by magic, that wonderful system, weakening, then provided us with perfect conditions to attempt crossing the notorious Ballina river bar.

For six days and nights we sailed with the same high-pressure system slowly backing round to the east. This we used to close with the coast, and as if by magic, that wonderful system, weakening, then provided us with perfect conditions to attempt crossing the notorious Ballina river bar.

From 50 miles out, a telephone chat with the Ballina Coast Rescue gave us the encouraging news that the bar was “passable with extreme caution.” With weather and sea conditions set to moderate further, we altered course for home.

Some voyages are tough and terrible, others are just hard yakka, while a few become wonderful experiences with every aspect perfectly right. That last night we sailed smoothly along under an easy breeze, interrupted by numerous rainsqualls that kept us busy and had us wondering whether we’d made the correct decision.

HOME ! AFTER 873 N.MILES

First light saw us romping along closing the coast fast enough to lure a small tuna. So fast we arrived off Ballina too early for the incoming tide, so we hove to a few miles offshore with the end in sight. While we waited, we watched the swells sweep past. Some big ones had us worried about the bar.

But in fact this story has nothing but a fine outcome because when the tide was half up, under full mainsail we bore off to actually sail across the much feared Ballina bar to the hoots and greetings from our family and few friends. Hearing the excited cries from our grandchildren are sounds we’ll always treasure.

Once inside, the good ship Banyandah continued her sail upstream, and not until we were next to the town jetty did we need to engage her engine to come alongside after a voyage of 873 nautical miles. That’s 1616 km for nix. Just the two of us. How’s that!

After landing, our world went crazy. Grandkids piled aboard with big hugs, followed by pulling ropes, cranking winches, jumping up and down from the upturned tinny, and of course steering the boat uttering proper boatie sounds.

Completely buggered after they took off home for dinner and bed, my honey and I nipped off for a quiet meal and a fine bottle of red. Then to a quiet non-rocking bed secured to a jetty. Logbook closed at the end of another amazing journey.