Bruce was a dreamer who was supposed to be our children’s teacher when we sailed for Africa many years ago. A horizon gazer, he’d sit for hours sublimely happy to just stare at the faraway blue line while distant thoughts filled his mind. He didn’t stay with us long. Instead, his short voyage on the Banyandah set him on a new direction through life.

Bruce was a dreamer who was supposed to be our children’s teacher when we sailed for Africa many years ago. A horizon gazer, he’d sit for hours sublimely happy to just stare at the faraway blue line while distant thoughts filled his mind. He didn’t stay with us long. Instead, his short voyage on the Banyandah set him on a new direction through life.

Hopefully you will forgive me if the following sentences ramble or their construction is loose for we have been out in the wilds these past three weeks and I’m still connected to Earth in a rather feral fashion that requires little precision.

Early in March, stored up with fresh food and grog, under headsail alone we sailed from Mill Bay, a wonderfully secure hideaway next to the tiny hamlet of Strahan in western Tasmania. First stop, Swan Bay, a torturous place to enter but which boasts absolute security from Southern Ocean storms and the last connection to a phone tower before the communications abyss further down Macquarie Harbour. That night Jude chatted with her sister in England then we got an update on our house from neighbour Achim and both of us giggled with our grandkids before sailing into that abyss.

Although the weather of these past weeks has been less than perfect, in fact maybe because it was not, has added to our pleasure. Tasmania has experienced a poor summer, and autumn has carried on in the same vein of cold wet conditions. These conditions have been exacerbated by where we’ve been, ringside aboard Banyandah, horizon gazing on a world heritage river surrounded by tall mountainous rainforest draped in mist and sticky cloud. We’ve been lost in space, just the two of us looking for adventure with supplies enough to last forever or even longer if we made a few sacrifices.

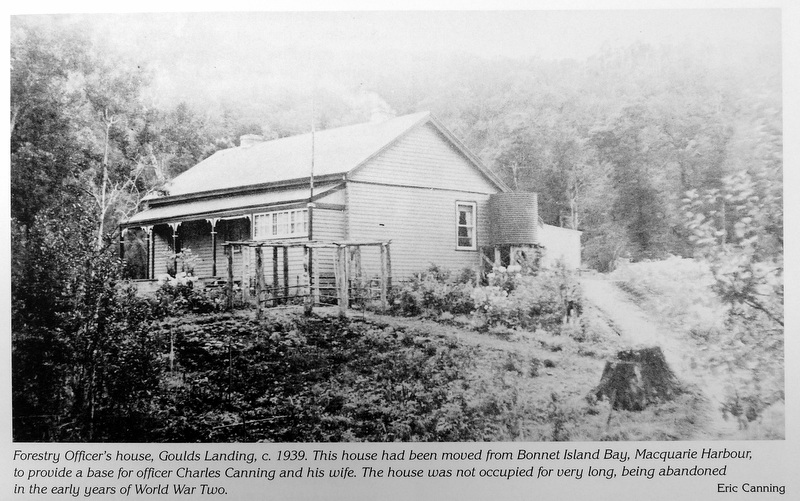

In addition to the beauty and solitude, we had come upriver on a mission. Years ago in the pining days there were various ways to get the logs to the river dependent on distance and available power. Early in the 1800s the convicts used rolling roads or the centipede system where gangs each side would carry a log. Later the piners used block and tackle when the trees grew near a river, but those logs that were further inland eventually brought teams of Clydesdale horses into this wild land. In the 1930s, towards the latter end of the pining era, the horses and supplies for the piners working the upper reaches of the Gordon were taken upstream aboard steamers to near the end of its navigable section where they were unloaded at Goulds Landing next to Sir John Falls. Residing in the house on the crown of the hill looking downstream a Forestry Commission officer recorded each log as it passed.

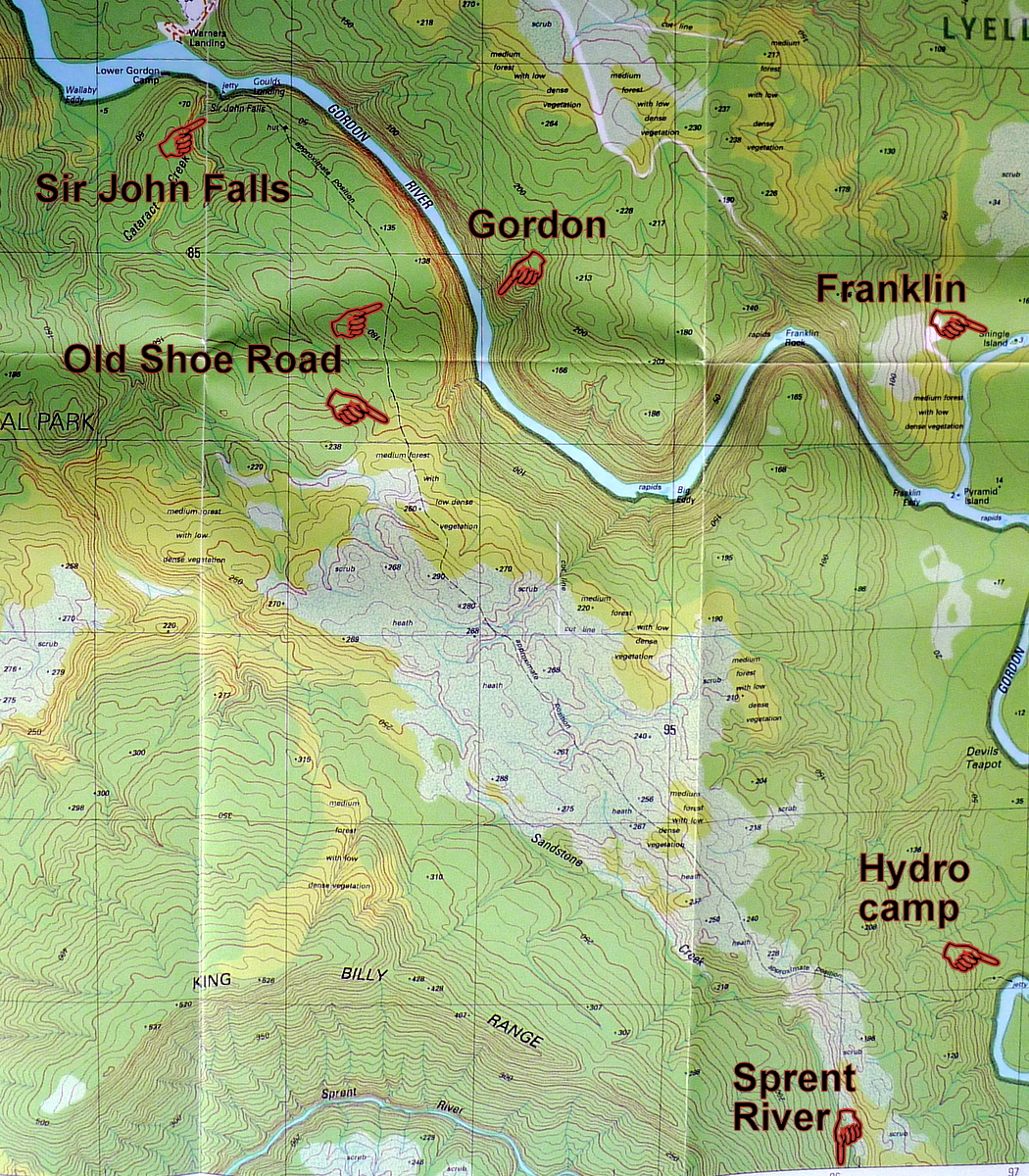

From Goulds Landing ran what is called a “Shoe Road” where the horses packed supplies to the upper reaches. This traffic wore a trench in the earth through what remained of the flattened forest, up to a buttongrass plain and then onwards to the Rocky Sprent River and Sandstone camp and further inland. In later years, The Hydro Electricity Commission used this track to bring supplies to their camp downstream of the Rocky Sprent. Today the forest has recovered lush and thick, but even now the remains of the shoe road in the buttongrass can be seen from satellites. Google Earth shows it clearly and it’s marked on the government topographical map as a dashed line.

Where the track crosses a ravine about three kilometres up from Goulds Landing, when we zoomed in close with Google Earth a vague shape of something like a bridge could be seen. The track runs up to it and then afterwards carries on across the buttongrass. The bridges made by the piners were mostly from Huon Pine and several still remain standing to this day. So we got wondering whether what we saw on the satellite image was another and got a hankering to reach it through the forest.

By some sort of miracle we sailed under brilliant sunshine from Swan Bay down to Farm Cove which has the most outstanding views of Mount Sorell. Entering that secure pocket of water the series of ghost white rocky peaks popped out the treeless buttongrass slopes, stark, hard, and majestic. No one witnessed our fast entry with Jack and Jude blissfully mastering what had become a boisterous blow knocking Banyandah about as she clawed upwind of Soldiers Island against white wavelets. Parking our lady after a magical sail past the increased numbers of fish farms we looked up and recalled our successful climb to Sorell’s peaks in 2012 after failing to reach the ridgeline our first attempt in 2009. To see that adventure and the superb views from atop a west Tasmanian mountain watch our Tasmania 1 DVD. While gazing upwards at those peaks, visions of bleached stunted trees tortured by countless wintry gales had us yearning to take a day walk up to the plateau to see again the splendid view over Macquarie Harbour and the mountains dominating it.

Without a fixed agenda the day after doing that we paddled the Green Machine around the cove’s shoreline spotting several species of ducks, a large flock of white billed coots and several nervous black swans who noisily took flight in pairs as we approached. Getting out at the narrow neck we took the short walk across to the harbour beach which disappointed us greatly. The beach facing the increased numbers of fish farms was littered with bits of plastic rope and pipe, and other manmade flotsam. Amazingly, we also found chunks of a yellow substance that floated and we wondered if we’d found pieces of amber.

Loving our freedom in the wide open space we sailed under headsail alone, leaving our rain awning stretched tightly atop the furled mainsail to shelter us from the frequent showers. Just a short sail around the headland and into Kelly Basin, plonking the anchor down under sail directly off Reindeer Lodge on a waypoint we’d made a few years earlier.

The Bird River track starts from the eastern side of Kelly Basin at what was once the township of East Pillinger where in 1898 a railroad brought copper ore down from the North Mount Lyle Mine. Cut through thick rainforest by hardworking immigrants and work hungry locals, that railroad lasted a mere few years before the amalgamation of two mining companies saw the forest reclaim the land. Today the Bird River Track is on the easy rising railway bed through what is again splendid rainforest. Not even the threat of a rainsquall prevented us from enjoying that walk again, although we were disappointed that Parks had removed the picnic benches from alongside the scenic Bird River Bridge and rushing river. We found them instead several hundred metres up the road in the car park where there is neither a view nor sound of the beautiful river.

Surprising us, a feisty northwest wind sprang up the next day, and yes we were at it again. Love the headsail/awning combo that took us to the Gordon River mouth, then through the first gorge with a blustery wind astern producing high excitement all the way to where the river turns north. The last fifteen miles up to Sir John Falls we took in several easy day hops under engine. Who could be in a hurry when the inclement weather was perfect for gazing upon the mist shrouded mountains that were definitely not suited for trail blazing.

But given enough time, the weather gods gave us our moment. We gave the forest a day to dry out then on the second beautiful day we began our trek. Climbing out the dinghy through the tree limbs we followed the deteriorating track found directly across the stream from Sir John Falls to what remained of the forestry commission house. Reg Morrison had purchased it during the war when most of the pining had ended and floated it back to Strahan in pieces to use some parts to build the Morrison’s mill on the jetty at Strahan. In fact the iron on that mill once sat on the hill overlooking the Gordon above Goulds Landing. Today little remains of the house that once commanded a broad view down river. Just two collapsed fireplaces and a vibrant hydrangea bush full of flower, rather out of place in the dark landscape. Nearby, setting a great scene stands the rail trolley and hand winch used to pull loads up the hill from Goulds Landing.

But given enough time, the weather gods gave us our moment. We gave the forest a day to dry out then on the second beautiful day we began our trek. Climbing out the dinghy through the tree limbs we followed the deteriorating track found directly across the stream from Sir John Falls to what remained of the forestry commission house. Reg Morrison had purchased it during the war when most of the pining had ended and floated it back to Strahan in pieces to use some parts to build the Morrison’s mill on the jetty at Strahan. In fact the iron on that mill once sat on the hill overlooking the Gordon above Goulds Landing. Today little remains of the house that once commanded a broad view down river. Just two collapsed fireplaces and a vibrant hydrangea bush full of flower, rather out of place in the dark landscape. Nearby, setting a great scene stands the rail trolley and hand winch used to pull loads up the hill from Goulds Landing.

Standing on the flat ground in front of where the house stood it was easy to imagine bales of chafe for the horses and other supplies waiting to be hauled overland to the tree harvesting area. Following the obvious route further up the slope we picked out the beginning of a trench about the width a packhorse would make and made our first GPS position. Jude and I followed it into the thickening forest, our hearts beating faster from exertion and gleeful anticipation. Now imagine being totally surrounded by thick green forest, its floor thick with decaying branches and soft fallen leaf. Beneath the canopy is eerie. Even on a bright day sunlight barely pierces through. Now keep still, nothing is moving, and that stillness is timeless as if nothing could possibly ever change. That must be why our imagination could hear the clop of a horse’s hoof and a whinnying neigh.

Going up the rising slope, the shoe road got deeper. Its vertical sides, eroded by years of use and wild wet weather, were coated deep green in what we were sure would sparkle with glow worms once darkness fell. It would then be a spooky world. In night’s darkness strange rustling noises from unseen beasts would alarm anyone trapped within the twinkling vertical walls. It was easy to scamper under the first fallen tree but ahead three others crossed the trench requiring us to crawl under on our hands and knees. On the other side, as if crossing into a primeval world, all around us there was not a sign of man’s interference.

Jude and I are experienced wilderness trekkers in both open and closed forests. We have good balance, nimble bodies, and good eyes for what is natural or not. But that south-western Tassie forest is a tough one. The forest has grown back thick, and older trees have blown down. Razor grass and dense spaghetti vine fill open voids as does the wicked horizontal, Anodopetalum biglandulosum, a small tree endemic to western Tasmania. As horizontal grows, the trunk bends under its own weight until parallel with the ground. Vertical branches then grow from these which also bend over in time; hence the tree becomes a tangled mass of branches. Combine all those elements into one area and it’s an unpassable mess.

Jude and I are experienced wilderness trekkers in both open and closed forests. We have good balance, nimble bodies, and good eyes for what is natural or not. But that south-western Tassie forest is a tough one. The forest has grown back thick, and older trees have blown down. Razor grass and dense spaghetti vine fill open voids as does the wicked horizontal, Anodopetalum biglandulosum, a small tree endemic to western Tasmania. As horizontal grows, the trunk bends under its own weight until parallel with the ground. Vertical branches then grow from these which also bend over in time; hence the tree becomes a tangled mass of branches. Combine all those elements into one area and it’s an unpassable mess.

With some difficulty we could detour around the fallen trees and on the rising slope could find the deepened shoe road again. But once we reached flatter ground we came across numerous small gullies, each looking vaguely like a manmade trench covered by thick patches of vine and heaps more horizontal. At that point, with about a half kilometre to the lighter forested area shown on our map, we chose to follow the path of least resistance and hopefully to forge ahead to find the shoe road where it emerged from the forest onto buttongrass. But by 1:30 PM we knew this was futile. There was zero chance of us reaching the buttongrass with anywhere near enough light to return home. Reluctantly, with a feeling of failure we made a turnaround waypoint on our GPS then looked back with deepening despair. Our legs were turning to jelly, our shins bled, and with increasing trepidation we badly needed an injection of energy and true grit.

Silently we ate our lunch in a mild clearing while studying the topographical map and dashed line depicting the approximate route of the old shoe road. According to that we needed to be more east by a few hundred metres. Therefore after lunch we went that way hoping to pick up some sign of the old road. We’ve got to say it was heavy, slow going that couldn’t be rushed or we’d have a medical emergency which was paramount to avoid. Never did we spy any of our red ribbons, just dense saplings, occasional large trees mostly Myrtles and Blackwoods, and old cut stumps of Huon Pines, but always lots of obstructions like horizontal and razor grass. But then about 3 PM, we happened upon a whitish flat object half buried in the forest floor. My eye must have been attracted to its plain flatness in an uneven field. I knelt down and was astounded to pick up a short piece of dressed timber like part of an old sign. It didn’t have any signage remaining but Jude photographed it and I recorded its position before moving on towards a slightly more open spot. There I was very pleased to spot nailed to a tree the diagonal sign used by Tasmanian Hydro, a yellowish square with a faded red circle. Looking more closely, there were signs of human disturbance and enough change in landform for me to know we’d again found the shoe road. From that point back to our last known position filled in a large portion of missing data that made our efforts that day very worthwhile.

Silently we ate our lunch in a mild clearing while studying the topographical map and dashed line depicting the approximate route of the old shoe road. According to that we needed to be more east by a few hundred metres. Therefore after lunch we went that way hoping to pick up some sign of the old road. We’ve got to say it was heavy, slow going that couldn’t be rushed or we’d have a medical emergency which was paramount to avoid. Never did we spy any of our red ribbons, just dense saplings, occasional large trees mostly Myrtles and Blackwoods, and old cut stumps of Huon Pines, but always lots of obstructions like horizontal and razor grass. But then about 3 PM, we happened upon a whitish flat object half buried in the forest floor. My eye must have been attracted to its plain flatness in an uneven field. I knelt down and was astounded to pick up a short piece of dressed timber like part of an old sign. It didn’t have any signage remaining but Jude photographed it and I recorded its position before moving on towards a slightly more open spot. There I was very pleased to spot nailed to a tree the diagonal sign used by Tasmanian Hydro, a yellowish square with a faded red circle. Looking more closely, there were signs of human disturbance and enough change in landform for me to know we’d again found the shoe road. From that point back to our last known position filled in a large portion of missing data that made our efforts that day very worthwhile.

Heavy rain fell the next day. Kicking back in the aft cabin, licking our wounds, Sir John Falls roaring loudly a short distance from the jetty, suddenly there came high pitched voices and laughter. Sliding back the aft cabin hatch we were astounded for there stood a gaggle of school kids. Crikey! How did they get here? Quickly we learned they were all year tens, ten of them, part of a high school outing with two teachers and a kayak guide. They’d paddled up from the Boom Camp in the lower reaches. How outstanding to learn that these week long outings were a regular event for Launceston High School.

Next day in the pouring rain those fortunate children rigged up a kayak with ropes tied to trees and ferried themselves across the creek then trekked up to the abandoned Forestry House site. This got Jude and I thinking how great it would be if the old shoe road was open and passable. School children and ordinary folk alike would then have an opportunity to experience one of the grandest forests of our world. It would allow all of us to see the many trees and shrubs that flourish in the harsh wet climate found here. And it would also give us an opportunity to better assess what our forbearers had to endure to eke out a living bringing the unique Huon Pine to the greater world. It felt such a shame that this historical track had not been kept cleared and we thought that a valuable asset had been lost.

Saturday a week ago we were enjoying a day’s outing with two kayakers who had been camping in the river as long as we’d been there. It was their wedding anniversary and we had planned a romantic stroll up Little Eagle Creek and were making our way along Limekiln Reach when a speedboat suddenly appeared around the lower river bend. It’s unusual to see a speedboat in the Gordon which has a six knot speed limit, but our concerns turned to alarm when we saw that it was the Police Boat. Fenders were flicked over her side as she came up to us and after we’d grabbed a hold of her railing a young constable appeared. Then a Sergeant popped his head round from the steering position and said, “You must be Jack. And you must be Jude.”

Next a cardboard box suddenly appeared. “A care package from Trevor,” he said with a twinkling smile as he handed it across. That was startlingly enough, but he then added, “You’re son’s worried about you two.”

I must have done a double take because he went on to say that our son had reported that our ‘yellowbrick’ hadn’t recorded a position since the last phone contact with him three weeks ago. And while I turned to unlatch our ‘yellowbrick’ to check, he continued. “I rang a few folk in town. Trevor saw you a week ago, and Geoff (the seaplane pilot) said you were at Sir John Falls two days ago so I rang your son and told him that you were okay. Trevor said that if we came looking he’d give us a package for you, and since it was time for us to check out the river, on such a fine sunny day we thought we’d come up. Now! Aren’t you going to open the box? We’re dead curious.”

You can imagine that after three weeks away from a shop neither the kayakers nor we had much fresh food for their celebratory anniversary dinner that afternoon, and so we were absolutely delighted to open the box and find salmon steaks, broccoli, fresh bread and a chocolate bar. How perfect! Isn’t friendship wonderful?

The yellowbrick not performing turned out to be human error. Mine! I had forgotten to pay the line rental….Dah!

Overall our few weeks in the wild were as good as it gets. It was an event worth far more than the humdrum of everyday life. Of course, Jude and I are totally in love with Earth. Be it rain, drizzle or sunshine the natural Earth holds so many mysteries, begs so many questions, challenges us like nothing else can, and gives a reward not found in any other human experience. Protect Earth, she is life.