Hermit’s Camp at Hidden Bay ~ April 30

Have you ever been to a place, even briefly, and been so moved by its beauty that you dreamt of escaping there again, thinking to recapture that sublime moment when Earth’s magic filled you with the hope that our planet can survive the human experience.

Have you ever been to a place, even briefly, and been so moved by its beauty that you dreamt of escaping there again, thinking to recapture that sublime moment when Earth’s magic filled you with the hope that our planet can survive the human experience.

Well! We found such a place, almost as far from mankind as one can get and still be on Earth.

But to get there we exposed all our treasures to danger because this place has both an angel’s smile and devil’s grin. And while there that brief moment we continuously monitored sea and sky, worried over harbingers of destruction, and thinking next time we’d march across the deserted land after first mooring Banyandah in a safe haven. Years then drifted by until an opportunity to revisit Tasmania’s far south coast became a reality.

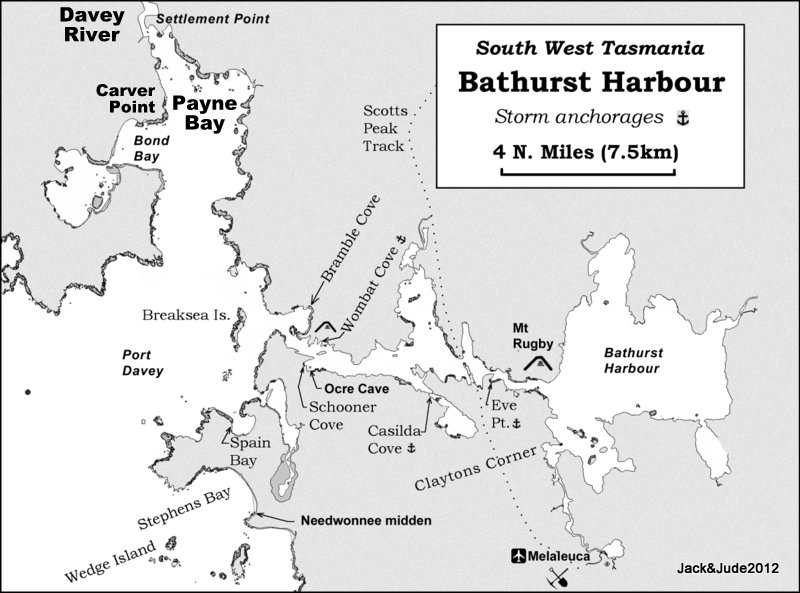

When I last wrote we were speeding away from The Davey River Gorge, rushing Banyandah for the safety of Bathurst Channel to bunker her down against a strong gale that when it struck pelted down marble sized bits of ice. For two days, we stuck well in the thick gooey mud of Frogs Hollow. And when the weather cleared, many visiting vessels hightailed it around the capes to Tasmania’s east coast.

You beauty! That left the jetty at Clayton’s Corner available. And our luck continued when a large high-pressure bubble lingered in The Bight. Not one to look a gift horse in the mouth, we quickly packed our rucksacks, strapped them on top the Green Machine, then after shutting all sea-cocks, Jude and I paddled away on a new adventure, hoping to again experience Earth’s wild beauty.

Our journey began when first light landed on Win and Clyde’s historical tin roof, the one shifted from Bond Bay after their ten years hard living, isolated, the furthest southwest of any Australian. Pretending we were in Deny King’s ‘blue boat’ and remembering his life, we paddled the five miles up Melaleuca Inlet and through the lagoon into Moth Creek taking two hours. The day before, two Friends of Melaleuca had visited and when discussing our plans, they suggested using Deny King’s old derrick to remove our Green Machine from the waters of Moth Creek.

Eventually we found ourselves loaded with backpacks, on the same boardwalk that takes walkers across flat buttongrass plains to the arduous south coast track. After an hour of absolutely nothing manmade in sight, at the crossroads we changed direction for the notorious Southwest Cape. Bounding our horizons, abrupt mountains lay bare except for the ubiquitous yellow green buttongrass spread evenly over every bump. This wet southwest averages 249 rain days a year so underfoot can be muddy mush, and the tiniest crease can become a raging creek.

In years gone by, fires from Signal Hill signalled a rare mail delivery. But on this day, no smoke clouded the heavens as we plodded through mud and slush, dodging the deeper pools only to slip a boot under at the next creek.

With waning energy and lessening enthusiasm, it became hard yakka to negotiate the last hill down through lush mossy rainforest, emerging to view small surf breaking on a vacant beige beach slashed by a deep black stream oozing from the buttongrass plains. Jude, lugging a 15-kilo load, looked dismayed to have to wade across that obstacle for a place to camp.

Then voices ahead urged us to follow the creek, now appearing like a silver ribbon, until we were amazed to spy a set camp in a clearing under myrtle trees. Moments later we were thrilled to be meeting Deny King’s daughter, Janet Fenton and husband Geoff along with two friends, and have an invitation to join their camp. Once established, we wandered from under the canopy as the setting sun cast red flames down upon the meandering silver, while from behind the hills, pink primrose and golden rays shot up into the heavens.

Needless to say we slept like two zombies, drifting off into a world where purple mushrooms talked and towering swamp gums walked. Opening our eyes after what seemed seconds found the dim light of next day. Thick fog swirled about, and we thought ourselves still dreaming until we heard Janet’s voice calling us to a wonderful photo opportunity. Supercharged by those words, my lady jumped out her sleeping bag while reaching for her cameras. Hardly a step behind, I had the video purring, capturing wispy mist swirling along the dark creek, where in shadows at the base of those hills lurked the monsters seen in our dreams, and they seemed to be moving towards us through swirling mist.

A golden orb burnt away that mist, revealing a glorious blue ocean extending unobstructed to the far South Pole, except for tiny Maatsuyker, Australia’s southernmost continental shelf island named in 1642 by Dutch explorer Abel Tasman. Across that narrow gap some of the world’s most powerful seas can be generated by winds sometimes gusting 100 knots.

Standing on this exposed beach at New Harbour, as we had done a few years earlier, we again observed a strange phenomenon. Each swell was turning from white to pink, then red as it peaked. And I remembered the clumps of red gelatinous material floating about Banyandah on our first visit, and soon cast my eyes on the felt-like blanket dried on the beach. Janet remembers always seeing it here, even in her childhood. But not on any other South Coast beach.

Standing on this exposed beach at New Harbour, as we had done a few years earlier, we again observed a strange phenomenon. Each swell was turning from white to pink, then red as it peaked. And I remembered the clumps of red gelatinous material floating about Banyandah on our first visit, and soon cast my eyes on the felt-like blanket dried on the beach. Janet remembers always seeing it here, even in her childhood. But not on any other South Coast beach.

Janet Fenton’s party hiked out mid-morning and shortly after Jude and I hefted rucksacks to continue over the next ridge into Hidden Bay. Up we climbed through even lusher greens now dripping with morning dew that sparkled in the hot morning light. Then magically after a stiff slog, we emerged into completely open spaces, the view snatching away our gasping breath. The purest colours of Nature had our cameras whipped out to capture that oddity of blue turning pink then red. From that high vantage point we could see great clouds of a rose bloom discolouring the bay and we wondered why just there!

That day we left behind the last of Earth as it’s known to enter a very private domain. Upon a trail without footprints, we forged through a littoral rainforest then down a sand hill to a bay where large foaming breakers smashed into cliffs of white granite, the noise shaking the earth as we strolled towards a rivulet flowing out between twin sand mounts that then crossed the beach. Following that waterway into the forest we found a mini-bit of paradise lost. By that creek a brilliant white sand strip entered an open tea tree forest neatly carpeted in leaf mulch, perfect for our camp. Protected from the wind, birds sang in the forest as we gazed upon a wide-open vista just a step away from drinking water that had me thinking a hermit could happily live here forever.

After setting up camp we set off exploring our Hidden Bay and immediately grabbing our attention were tiny footprints loping across the smooth sand. Tiny toes with sharp nails were laid down in a pattern indicating the creature didn’t hop. Later we had the joy of sighting a Tiger Cat, its long thin tail half again that of its body.

I could fill pages on the charms of this remote spot, but moving on; the next day we scaled the ridge separating Hidden Bay from New Harbour. Leaving the rough track to chance finding a way to the ridge through scrub and buttongrass proved a brilliant move, but not something you’d do unless experienced bushmen. Climbing steeply, our cumbersome rucksacks held us back, so it was fortunate we soon found the remnant of a long disused track. Who knows! Perhaps one used by Deny and his dorts. The track wound up past a small waterfall, then breasting the ridge a long held dream was fulfilled when our gaze fell upon the spectacular view across both bays, silky smooth and domed by an eternity of cerulean blue, the colour of peace.

Like fingers tracing a map, our eyes followed a coastline rarely visited, sighting first New Harbour rocks – bold, craggy, looking dangerous, obstructing the entrance to our first camping bay. And as we gazed, our mind’s eye could see Win and Clyde, once trapped inside that bay by gale formed combers that forced them to abandon their small fishing craft and jump into storm seas, no doubt praying to their maker.

All those who challenge the elements know the wildness of Nature can easily snuff out life’s breath. But to risk life is necessary to gain the full experience of ones short time on this amazing planet. Be it on land or sea, take precautions, remembering no matter what, there’s always risk. Slip off your ship or trip on a loose stone, both might end in a fatal fall. Struggle up hills or do battle with heavy weather might burst something internal. For Jude and I, that’s no reason to become a couch potato. Life is for living til the very last breath. It’s the opportunity to witness the creation. And if there is a God, surely he’d be pleased if we don’t muck it up.

A Paddle into the Past ~ April 22

In a dawn thick with cottonwool mist sucking up all sound and muting the throb of our six-cylinder engine, we started our journey into the long distant past by first negotiating the shallows off Carver Point. Somewhere through that wet mist, remnants of Carver’s shipyard lay hidden amongst thick mosses and logs fallen these many years since the Lady Franklin first slid into the waters of Port Davey, perhaps the last vessel hewn from local stands of Huon.

In a dawn thick with cottonwool mist sucking up all sound and muting the throb of our six-cylinder engine, we started our journey into the long distant past by first negotiating the shallows off Carver Point. Somewhere through that wet mist, remnants of Carver’s shipyard lay hidden amongst thick mosses and logs fallen these many years since the Lady Franklin first slid into the waters of Port Davey, perhaps the last vessel hewn from local stands of Huon.

Up into Payne Bay filled with nasty sharp rocks we navigated to a spot off the unseen Davey River Bar. In shallows that left only half a metre under our keel, we set the hook into something that sharply pulled our lady around to the sun bursting through, clearing the day to become one filled with endless blue above rolling hillsides of tawny buttongrass spotted by grey-white dolerite rocks, craggy and menacing. This was not a place to relax when leaving your craft.

Back in 1871, when travelling with a party including Mr. Piguenit of the Lands Department and Frank McPartland who was a top bushman on official business as constable from Picton; a Mr. James Scott noted at the northern extremity of Payne’s Bay, settlements on both sides of the Davey River. He wrote in the Mercury that a “Mr. Docherty the oldest resident, and a Mr. Carver with ship-building yards, and others, resided on the west side.” And that, “a Mr. Woolley and several families engaged in the pine trade lived on the east side. The population amounted, altogether including children in arms, to about 40.”

He writes of a township with houses “To Let,” but they encamped in what “once had been a garden, now a wilderness of ferns and strawberry plants, with a few apple trees and currant bushes. The tall tea tree along the beach has been left growing, and forms a good breakwind against southerly weather for the row of houses which are built behind it.”

He also told the people of Hobart in 1871, “Mr. Carver has a 60 ton schooner nearly ready to launch, built of the Huon Pine obtained up the river. The piners have to go some 15 or 20 miles up the Davey River to the timber beds… felling the trees in the summer months, branding the logs, and placing them in the water so that the first flood may float them down, where they are caught and fitted for market.”

Today the Port Davey Marine Reserve in the southwest of Tasmania is located within the boundaries of the Southwest National Park and the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Originally proclaimed in 1951, the Southwest National Park is classified as IUCN Category II – National Park, and is fully protected under the National Parks and Reserves Management Act 2002. The Port Davey Marine Reserve was proclaimed in 2005.

Whalers, sealers and piners (timber-cutters) first arrived in the early 1800s. Bay whaling stations were located at Bramble Cove and Turnbull Island. Pining villages were located near the mouth of the Davey River at Piners Point and Settlement Point, and another at Spring River. By 1890, with both whales and Huon pine nearly exhausted, Port Davey was largely abandoned.

Since the 1900s the area has seen only three long-term resident families: the Claytons, Kings and Willsons.

The Port Davey landscape could be mistaken for a glacial fjord, but is in fact a drowned valley or ria. Bathurst Harbour was once a large plain that flooded as the sea level rose about 7000 years ago with late melting of the last ice age. The geology of the area is largely billion year old quartzite’s, originating as sand and mud laid down in shallow seas, which over time were metamorphosed by heat and pressure into quartzites and schists, then uplifted, folded and partially eroded away. Younger conglomerates are also present.

The soils that cover much of south-west Tasmania are organosols – loosely referred to as peat. Organosols form from undecomposed plant material that slowly accumulates under extremely wet, humid and cool conditions.

But we had not come just to witness peaty soils and the few piner remains. Our main focus were the ancient rocks forming the Davey River Gorge, renown for their reflective beauty during calm weather.

While preparing the Green Machine for a paddle to Settlement Point, then as far up river as we could get, the boys off Melian, nearby in the western anchorage, dinghied over to ask if we’d like a tow up river. Our big smiles signalled ‘you bet.’

To Never-Never Land Again ~ 16 April

At the far southwestern tip of Tasmania, Australia’s largest island, lies a special place so far away from the known world you could easily think yourself on another planet. It’s impossible to drive to this extraordinary place – there are no roads for hundreds of kilometres. You might walk, but that would take six or seven days. Or you could hire a tiny aircraft and land on a miniscule quartzite airstrip hacked from wet buttongrass plains. But then you’d have no place to sleep, except on the ground, and have no way of exploring that magical land of rivers and mountains. So, by far the very best way of reaching this exotic kingdom is, you guessed it, by sailing yacht, approaching its majesty using Nature’s power to better become one with its vastness.

When I last wrote, Jack and Jude had been exploring Macquarie Harbour and the Gordon River for eight grand summer weeks. To stay another eight weeks would have been wonderful, but the seasons were changing and soon the mornings would be frosty, the clear nights needing a thick doona on the bed to stay warm. Reluctantly we farewelled all the friends we’ve come to love over our three summer visits, and prepared Banyandah for the unpredictable Southern Ocean. Inside landlocked Macquarie Harbour it’s easy to forget the feel of ocean swell, although we had often heard its distant thunder on ocean shores. While preparing at Mill Bay, hearing it rumble just over the hilltops prompted us to secure all bits and pieces very tightly. The Green Machine we folded up, packing its frames and bulkheads into two rubberised backpacks then stowing these on deck. Little Red, our alloy dinghy we lashed to the foredeck with emergency supplies inside. When all was ready, we motored out through Hells Gate, battling for the first time an unexpected incoming tide, the throttle well open. Then with the sun setting, Banyandah pirouetted around the training wall’s seaward tip and into Pilot Bay for a few hours rest in clear waters, protected from all but north to northwest winds.