February 2016 January 2016 >>

Blog of Jack and Jude

explorers, authors, photographers & videographers

A Walk in a Park

Pain and Pleasure

Oh my, we’re weary and stiff. Our feet sore. Our troublesome knees swollen. You may remember our mentioning that we had some unfinished business. We’ll, that’s why you’ve not heard from us for over a month. In our last note, posted as we lost contact with the outside world, we said not to worry, that we’d be gone a few weeks, maybe longer.

(A note for our regular readers; click here if you wish to skip the background/history and go to this year’s expedition)

Background

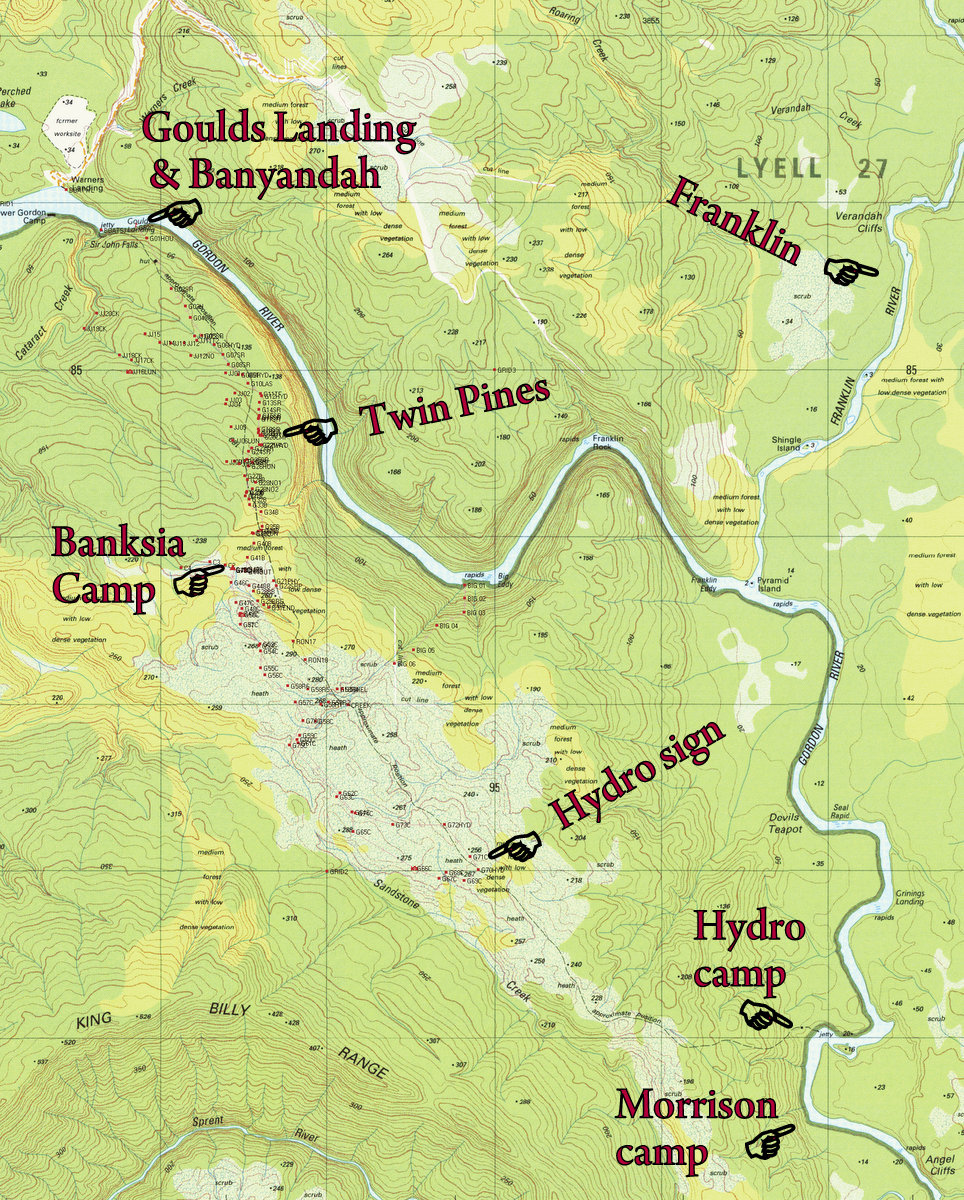

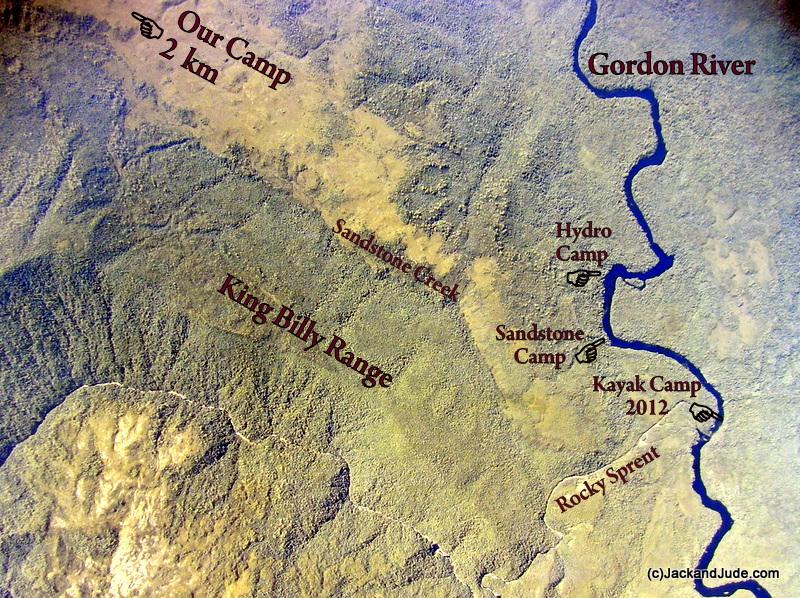

This story begins shortly after World War II with a group of very fortunate men that some of you may despise, but who were just doing their job, and in their own way were passionate about Earth like you and us. They worked for Tasmanian Hydro, and four times each year they would take the public tourist boat from Strahan to Sir John Falls, then over several days walked south through what is now The Franklin Gordon Wild Rivers National Park to a small Hydro camp on the Gordon just downstream from the Rocky Sprent. Their job was to measure river flow and height.Walking overland, their journey took them through the full display of Tasmania’s lovely land, from the thick wet forests near the river’s edge through regions of drier Manuka and Eucalyptus, and then onto one of those magical phenomena of southern Tasmania, a large open buttongrass plain. This one at the feet of the thickly forested King Billy Range.

History

The track they followed had been used by many in Tasmania’s past. Before Hydro, from about the 1930s to the 60s, the Piners used it to haul chafe and supplies to their upper river camps. Before that, a number of geologist and miners had used it to search for mineral resources. This track was first staked in 1863 by the team led by Tasmania’s first Geological Surveyor, Charles Gould (1834-1893) in their search specifically for gold, and later enhanced by Jim Morrison when he established a pack track from Goulds Landing, lying a hundred metres upstream from Sir John Falls, to his Sandstone camp near the Rocky Sprent.

Tasmania was Australia’s second colony and in the mid 1800s desperately needed additional resources, but attempts to explore Western Tasmania proved a highly dangerous nightmare. Thickly clad mountains and raging rivers blocked access overland, and huge seas and Hell’s Gate, then one of the world’s most dangerous entries, both combined to curtail the colony’s development. It became so desperate that in 1842, Governor Sir John Franklin ordered the young surveyor James Calder to find a path west. In charge of twenty convicts and a dozen solders that daunting task took two years. But the track proved highly weather dependent and twenty years later on, Goulds men found a much better route linking the west to the east.

So you can see that this trail has immense historical value. In fact it’s intrinsic to who we are as Taswegians and Australians, and epitomizes the courage and never give up qualities that we so greatly admire. Values we want to pass on to coming generations. As a society we should want this historical track to be kept open because it travels through a diverse range of geography, and by doing that, illustrates how nature copes with the various conditions of wind, sunlight, rain, terrain, and nutrients.

The first part of the track nearest Sir John Falls was once used to haul Huon Pine logs from the immediate area and is indented by dragging those logs that had a metal skid under their front end. These valuable logs, used to build many of our early ships, only grew within a kilometre or so from the river’s edge, and the furrow they carved, called a shoe road, records much history. Today, much to the incorrect beliefs of some, there are many Huon Pines flourishing in the SW forests, and a number of trees over a thousand years old grow alongside this part of the track. There are also many hundreds, maybe even thousands, of small baby ones right beside the track. It’s a wonderful spectacle. Proof of the indomitable will of Earth to heal and survive.

The one and a half kilometre run of Shoe Road, which we’ve named The Huon Way, is now safe enough for schoolchildren to walk along. It’s quite easy going, a very lovely walk in a park that will uplift your soul with the majesty of Earth. About two-thirds along is a suitable place to camp if you want to be totally immersed in the dark closed forest that borders these SW wild rivers. We dubbed it Camp Twin Pines when we spent several nights there early last year because it’s a small open area with seasonal water nearby, next to two five hundred year old Huon Pines. A little further along the well defined shoe road stands the last two Huon Pines, two large moss covered stumps harvested perhaps sixty years ago. Beyond these, abruptly starts a forest of mature Manuka, tall and slender, close together with shedding bark that dangles in thin strips making them look like hairy poles. The Hydro track then wanders through this for another kilometre that presently requires a greater skill level to follow.

Back in the 1860s, Charles Gould would have cut a cart wide track. The geologists and miners that followed him would have continued to maintain this by trimming regrowth and cutting away fallen trees lying across that track. The Piners did this too, as did the Hydro men. All regularly maintained an open pathway about a cart width, a mere ribbon through what is a vast country of natural land. None of this ever endangered the whole by even a smidgen.

But, after the area became National Park and the Hydro men stopped coming in the early 80’s, this historical track, which is an important part of our history, this path that tours the wonders of SW Tasmania has been left to be consumed and lost forever and become merely a dashed line on old maps.

Our Interest

You may be wondering what our interest is in this. Well, isn’t it strange how some things get started? Early last year we wandered up to Sir John Falls wanting to know more about the Huon Piners after taking part in the filming of Two Men in a Punt, a Garry Kerr production. After seeing an iron shoe at an up-river camp, we wanted to see a shoe road, made when a team of horses dragged a log out the forest. Goulds Landing once had a forestry officer’s house at the end of a shoe road, and not having visited it, we rowed Little Red from the jetty across the narrow gap where Cataract Creek enters the Gordon. This gap used to be spanned by the old jetty but now only the stumps are visible. Along that hillside we found a track, rather overgrown and blocked by fallen trees. But after a bit of a scramble we came upon a massive open area where in yesteryear supplies were stacked after being unloaded from coastal freighters moored alongside Goulds Landing. Metal angle and rotting timbers are all that remain of that jetty.

The Forestry House has long since been dismantled and towed downstream to Strahan – today some of its roofing iron protects the Morrison Mill in town, so only the two fire hearths remain testimony to a past era.

Finding the shoe road was much harder than we’d imagined even though the expansive area was fairly clear of understory. Crunching over a layer of fallen limbs filled with soft leaf litter we finally found a trace of the furrow under a tangled mess of tree fall comprising one massive tree head on top of a fallen giant that had taken down several smaller trees with it. Skirting this, the road became starkly evident – a furrow wide enough for three horses inline, worn in the earth to varying depths. In a straight line, it climbed the hillside, but was soon blocked by another, even larger, tangle of trees.

Back at Sir John Falls we found that a school class had made a camp on the flats above the jetty, and the dozen students and teachers soon gathered alongside Banyandah, wanting to know more about life afloat. From them we learned that they were on an annual orienteering course put on by Launceston High School and that they had paddled kayaks up from Heritage Landing after taking the ferry from Strahan. A great feat. So we told them about our day discovering the shoe road above Goulds Landing and like a swarm of bees got them humming with plans to make the same discovery.

Children Bind All Humanity

We don’t know how you feel but we believe children bind all humanity. Be they Christian, Muslim, black, white, oriental, African, American, or Australian, children are the common denominator. We all want them to have a wonderful life and to have at least as much happiness as we’ve had, and we want them to experience as much of Earth as is possible. Hearing the excitement in their young voices got us thinking how great it would be if the old shoe road was open and passable. Schoolchildren and ordinary folk alike would then have an opportunity to experience one of the greatest forests of our world. It would also allow all to see the many trees and shrubs that flourish in the harsh wet climate found here. And it would make possible an opportunity to assess what our forefathers had to endure to eke out a living when bringing the unique Huon Pine to the greater world. It felt such a shame that this historical track had not been kept clear and we thought that a valuable asset had been lost. So, early the next morning we went back and started clearing the dead branches we could lift to make a better, safer access without always having to look down or chance getting lost.

We did this day by day as a way of enjoying the great outdoors and as sort of a challenge to our bush skills, for the shoe road was quite difficult to find sometimes. After a half dozen sorties we left the forest and went back to town having strung pink tapes along about one kilometre of the track. We had made a start and at least next years orienteering class would more safely be able to penetrate that wonderful forest.

In town, an acquaintance had heard of our interest and came to us with a satellite photo showing what he thought might be one of the timber bridges built so long ago to cart supplies across some of the small creeks. Humm, it did lie on the magical dashed line representing the Hydro track on our topographical map, and it wasn’t that much further on from where we’d gotten. So, after taking on more supplies, we went back up river for another stint of track finding.

After the stumps of the last two harvested Huon Pines, a much reduced path wandered on for another kilometre and required a greater skill level to follow because the indented shoe road finished and every direction was looking exactly the same. In addition to the danger of becoming lost, there are other dangers in this region. Cutting Grass, or what we call Razor Grass, has long blades growing in clumps up to two metres in height with razor sharp serrated edges that easily cut arms, neck, eyes, and eyelids. We can testify to that.

As the terrain continued to rise, that broad band of Manuka gives way to larger trees of Eucalyptus. It becomes more open above, but under foot it becomes a jumble of fallen trees in various stages of rot. In such a wet climate, Eucs don’t last long on the ground. Therefore along the path of our pink ribbons are many fallen trees that must be climbed over, and many others, slippery ones, to walk along. Great care must be taken, not to slip or put a leg down a hole between them otherwise a broken bone might spoil your day by endangering your life and causing great inconvenience to your rescuers.

Surviving the Eucalyptus forest is marked by sighting a giant headless tree that may not survive many more winters. Beyond it our path became even more challenging.

There grows here in Tasmania a number of plants that are quite challenging to forest travellers. Cutting Grass or Razor Grass is one. Horizontal another. It’s a strange plant that begins by growing vertical then under its own weight bends horizontal to about shin height where along its length it sprouts new branches that grow vertically like a picket fence. Nearly impossible to penetrate unless you’re a double jointed midget. Fortunately this track has no horizontal along it. But there is another plant that’s even more insidious. It lies at the other end of the size scale. To those that know Tassie’s bush, nothing is more challenging, more draining of energy than Bauera. The mere mention of its name makes Tassie’s bushmen shudder.

HD format of Bauera – The Bushman’s Curse

It’s a pretty plant with a multitude of tiny bright green leaves along its stems, which grow like a nest of tangled snakes, around and through one another, branching into two that then splits to four, then eight, weaving a mass higher than man, often high up into trees. It loves to grow around and over other plants, and just loves weaving up an entire hillside with a net of cables that start at it base with something like 12mm reo bar before branching into many more about the diameter of a pencil, and then heaps more about the size of stout wire. Bauera is not only a daunting, draining task to penetrate, it’s also a bitch to pass over after it’s been flattened because it always catches a boot, or a strand just seems to jump up to act like a barrier.

From the headless Euc that may not last another winter there is a half kilometre of Bauera intertwined through and over fallen trees. No telling how long this passage will stay open. A few wet seasons will probably see our pink ribbons consumed by the green glory of Nature unless more folk walk our path. But once through this last barrier we arrived at a wonderful, open to the sky, bowl of buttongrass. Our mysterious bridge lay just over the next ridge.

Each of these sorties was taking longer and longer to return from, and we found that up to four hours of every outing would be taken up with travel along a path we’d already marked. So we took our tent up to Camp Twin Pines for a last effort at finding this mysterious bridge. Third time lucky we hoped.

By this time it was late-April and the days were getting shorter, the nights colder, the climate wetter, and our hobby demanding more true grit. But by this time we had fallen in love with the forests. We’d come to know the massive old Huon Pines, gnarly and grand, standing off track, and massive ancient myrtles that have such tiny colourful leaves, and cheesewood trees looking like tall creamy Swiss cheese pocked with small round marks, and blackwoods, and leatherwoods that in summer are transformed by a filigree of large white blossoms. The forest can be one of the quietest places, perfect for contemplation, but of course the forest birds woke us each morning and kept us company during our day, and they sang melodies in the evening when the sky grew golden.

Third time lucky proved to be just another pipe dream when we entered that thick small creek and found nothing but beautiful lush green vegetation and a tiny flow of water. Oh well, it had been fun and kept us fit, and had provided us with a great adventure. So we packed our kitbags and went home for the winter.

This Year’s Expedition

Banyandah endured a windy wet winter tied to our new mooring in Mill Bay, which lies just around the corner from Strahan, while up in northern NSW we enjoyed being with family and playing with our many grandkids. We sailed very few miles in 2015, just over a thousand, the fewest since relaunching our lady in 2005. Blame that on the magic of Tasmania and in particular its spectacular west coast.

Probably nothing more would have come of our exploring the Goulds track if we hadn’t on a whim decided to see how our handy work had survived the winter. To our disbelief and consternation we got lost the first time back after the winter break. Geez, a path we’d walked so many times led to a dead end. Of course that’s when we remembered all the many pink tapes we’d left during our fruitless searches. Even our second attempt ended in frustration and that prompted us to scratch our noodles while trying to recall just where we’d been. But a search of the area turned up a new Hydro sign, one not seen before. It was on a bit of shoe road not travelled on either. A few metres down it revealed one of our pink tapes and showed how we had come to be on it via a diversion around a massive tree fall. After that, our path became an easy walk in a park to Camp Twin Pines. Not wanting to leave behind misleading tapes we then spent part of that day scouring the hills for the unwanted ones, and left behind a very clear route. Now so easy to follow that we continued on through the Manuka forest, clearing up a few unwanted ribbons there also. Then went on to the headless Eucalyptus, which had survived the winter. Continuing ahead, the tunnel through the Bauera had closed somewhat, but was reasonably passable up to the open buttongrass basin.This must have been the trigger for a new plan. Because later that day when back on Banyandah, we simply gushed over taking our tent into that basin to continue our quest to reach the large plain lying over the last ridge where we imagined finding remnants of the Hydro track. We envisaged walking unhampered under the mighty King Billy Range, and couldn’t get out our heads the possibility of actually retracing the entire route to the old Hydro camp on the Gordon, which we had visited a few years earlier by kayak.

Tasmania’s winter and autumn had been the driest on record, so the forest floor was crunchy dry – scary dry in fact when thoughts of lightening strikes entered our heads. It might have been a pleasure not to have droplets drip down our necks nor have slippery slime on our pant bottoms, but there was no water to be found. At Camp Twin Pines, our three water sources found last year were dry sand. There were no colourful mushroom carpets and the trees looked stressed. We hadn’t checked at the buttongrass basin but thought there might be a flow from the streams that drain part of the King Billy Range and form the headwaters of Cataract Creek. It was worth the chance, so we packed up our kitbags for at least a week in the bush.

Carting twenty kilos on our backs along a path that degenerated from a walk to a crawl over fallen trees and through tangled Bauera tested our aging bodies. Amazingly we managed the outbound journey in about four hours, consuming half of the four litres of water we carried. Of course we carried other liquids. Can’t go bush without a libation to celebrate surviving each day.

Carting twenty kilos on our backs along a path that degenerated from a walk to a crawl over fallen trees and through tangled Bauera tested our aging bodies. Amazingly we managed the outbound journey in about four hours, consuming half of the four litres of water we carried. Of course we carried other liquids. Can’t go bush without a libation to celebrate surviving each day.

Finding a Camp

Therefore arriving at the half kilometre wide basin open to the heavens we faced our first big test. Find water. To do this we dropped our load then set off to where the map showed the confluence of two creeks. But somehow the basin seemed more dense than we’d remembered. There seemed more stunted tea tree, less open vision and we had a dilly of a time, weakened as we were, to reach the spot shown on our GPS. Approaching a rising hill where the two creeks supposedly met, the vegetation thickened and patches of Bauera appeared. Oh dear, maybe it’ll be a night sleeping upright then a bolt out the next morning. Dreading that thought, our deepening gloom was broken when from out the silence came the golden sound of tinkling water. Pushing aside the undergrowth, in a trench ran a lovely cold mountain stream. And right next to it, a massive Banksia, overgrown with heaps of dead, dry Bauera.

Recharged with a new jolt of energy, we cleared away the nuisance mess from round the tree, our smiles growing ever broader. What a perfect site. Carpeted with soft, springy mulch, there was ample flat ground for our tent, room for our clobber, and a perfect spot away from the stream for our toilet. Sundown that night saw us aglow in our camp toasting our good fortune. Of course there’s a lot more than just good fortune in this. We’re a hard working pair who are also a great team with skills complementing the other.

Camp Banksia proved heaven sent. You should do this walk just to spend a night there. Surrounded by a rim of ridges dotted with eucalyptus, the woods are alive with a variety of birds, all coming to feed on the blossoms. The Banksia seemed a favourite of the honeyeaters and thrushes, and the half dead monster on the hill opposite seemed the favourite haunt for a pair of Wedge-Tailed eagles, and when they weren’t there, pairs of cockatoos, and BooBook Owls could be heard at night.

Look, we could go into the arduous chore of finding our route, the tunnelling up another hill of Bauera that took an entire day, the doing the same on another hill leading straight to that magical dashed line, but let’s cut to the climax. After three days of hard yakka, we opted for the Bauera tunnel that led to a shallow valley filled with thin growth that looked as if it magically would take us to the open plain near the headwaters of Big Eddy Creek. On a cloudy cool day, not so good for photos, but excellent for finding a route, the plains that had looked so clear and easy in the satellite photos proved to be mostly shoulder height tea tree of a variety that has heaps of cup seedpods. Under them grow small tussocks of buttongrass. The two in combination made unsteady footing that had to be taken slowly, tentatively putting a foot down before transferring full weight. We had lunch overlooking the creek then went off to look for the Hydro track. Geez we went down into that creek, into the thick stuff again, found no running water, just a few tiny still pools, and we crisscrossed what should have been the dashed line shown on our map, but found neither Hydro sign nor their track.

Look, we could go into the arduous chore of finding our route, the tunnelling up another hill of Bauera that took an entire day, the doing the same on another hill leading straight to that magical dashed line, but let’s cut to the climax. After three days of hard yakka, we opted for the Bauera tunnel that led to a shallow valley filled with thin growth that looked as if it magically would take us to the open plain near the headwaters of Big Eddy Creek. On a cloudy cool day, not so good for photos, but excellent for finding a route, the plains that had looked so clear and easy in the satellite photos proved to be mostly shoulder height tea tree of a variety that has heaps of cup seedpods. Under them grow small tussocks of buttongrass. The two in combination made unsteady footing that had to be taken slowly, tentatively putting a foot down before transferring full weight. We had lunch overlooking the creek then went off to look for the Hydro track. Geez we went down into that creek, into the thick stuff again, found no running water, just a few tiny still pools, and we crisscrossed what should have been the dashed line shown on our map, but found neither Hydro sign nor their track.

The next day being even cloudier we took the whole day off. We needed time to stitch up our gloves and repair our torn pants. For relaxation we read aloud to the other from Robinson Crusoe, ate lots of nice food, and took an afternoon nap.

Early on our sixth morning it was still heavily overcast but we dressed to make our final charge to the huge open plain under the King Billy Range. But just before leaving we heard distant voices. A bushman’s cooee brought a reply and soon we had visitors, five of them to be exact. They were off other boats, had heard of our hobby, and on a whim followed our pink tapes. They were much younger than us and had taken just a bit over two hours to travel what had taken us months to locate and mark. Wow, we were stoked! And they were soaked because they brought the rain.

It continued to rain all our seventh day. Not heavily, just drizzle that creates that lovely misty look. And when that was replaced by the Southern Cross and pointers later in the evening, we went to bed filled with anticipation of a big day exploring a destination we’d work so hard to achieve.

Final Assault

Day eight began with a rare argument. Can’t remember what the issue was but it was an ominous start under a sky heavy with morning cloud. After we’d navigated the Bauera tunnel and came out in the shadow of the ranges we kissed and cuddled, our great love for the other nicely putting a spring to our steps.

We had two goals that day. One was to capture some of the magnificent beauty of the wild river mountains that’s filled with so much colourful vegetation. The second was to find proof of the Hydro track. So we literally zoomed past our earlier lunch stop, skirted round the headwater dip of Big Eddy Creek, and headed into new territory.

Instead of being an absolute flat plain, it’s dotted with numerous small hills, some with clumps of slender trees, and some of these surrounded with dense bush. Between the King Billy Range and the plain are the headwaters of Cataract Creek flowing north, and the Sandstone Creek running south. Where the two headwaters meet there’s a land bridge joining the plains to the mountains, and it was to this point that we first headed. The going wasn’t easy nor was it hard. We didn’t have to forge our way through the vegetation that varied from mostly waist height to open patches on nutrient poor ground, to shoulder height growth where conditions were better. We mostly just parted the growth with gloved hands, stepped tentatively forward, often over a clump of stunted buttongrass, then moved on repeating the process. We left very few pink tapes. No purpose in doing that as we could see all the landmarks and could go in just about any direction. But we did record our movements with GPS waypoints, and had the luxury of transmitting our position via the Iridium satellite network using our fabulous Yellow Brick. We really hope many of you followed our exploits live as they happened.

On the higher hill separating the two headwaters from mountain and plain, we got some outstanding top of the world views. Providence shone down upon us under a now perfectly clear sky that allowed us to behold the great majesty of the Franklin Gordon Wild Rivers. Off to the furthest nor’ east we saw the lofty Elliot Range drop into the Franklin River valley, which ran towards us to enter the huge Gordon River valley that spanned our entire view. Along it to the south we traced the Sandstone Creek to where it enters the Rocky Sprent. We could see where the Hydro camp must be and just a titch south of it, still on the Gordon, lays the Morrison’s Sandstone Camp where we had filmed the remains of the stables, meat safe, and moss covered Bluntstone boot. Those Piners would have had a tough life out here in the cold wet wilds, but what a glorious magical place to work. It’s a Godly place. Where souls are in direct contact with the creator. A simple life, a fulfilling one, one counting on your mates and they relying on you. Those images and thoughts had us wondering where the world is heading now.

On the higher hill separating the two headwaters from mountain and plain, we got some outstanding top of the world views. Providence shone down upon us under a now perfectly clear sky that allowed us to behold the great majesty of the Franklin Gordon Wild Rivers. Off to the furthest nor’ east we saw the lofty Elliot Range drop into the Franklin River valley, which ran towards us to enter the huge Gordon River valley that spanned our entire view. Along it to the south we traced the Sandstone Creek to where it enters the Rocky Sprent. We could see where the Hydro camp must be and just a titch south of it, still on the Gordon, lays the Morrison’s Sandstone Camp where we had filmed the remains of the stables, meat safe, and moss covered Bluntstone boot. Those Piners would have had a tough life out here in the cold wet wilds, but what a glorious magical place to work. It’s a Godly place. Where souls are in direct contact with the creator. A simple life, a fulfilling one, one counting on your mates and they relying on you. Those images and thoughts had us wondering where the world is heading now.

Over lunch somewhat spoiled by numerous March Flies we discussed coming back one day with our camp so that we can explore further and maybe reach the Hydro or Morrison’s Sandstone camp overland. Water would be the problem. The only water we’d seen was at Banksia Camp. But maybe we’d find some in the Sandstone Creek.

We also planned a return to our camp that would take us to that dashed line shown on our map in the hope that we’d find a remanent of the old historic track. The finding of it had risen greatly in our goals so we measured a point on the map where the dashed line crossed a meridian and entered the new destination.

Satisfaction

It was three o’clock and we’d been underway six hours when that waypoint led us around a second dry creek, even further south away from our camp, deeper into the plains. Ahead lay a patch of grey boulders sprouting from the growth, above them a hilltop grew thicker, causing us agitation. At a time when we wanted to be heading home for a comfy change out of boots, difficult country loomed ahead. Small trees thickened with undergrowth covered that hilltop and we were about to divert around it when a strange glimpse of something odd caught my eye. I looked again but couldn’t find anything odd amongst the stems and bushy heads and turned to head away, when again something odd, something unnatural. Rocking back and forth to gaze past the growth, I saw a regular shape amongst the growth.

“Yahoo!” I yelled, alarming Judith. “There’s a Hydro sign.” And rushed forward praying I’d not just imagined it. I hadn’t. Standing tall on a metal stake stood a yellow metal diamond with that familiar red dot in its centre. Geez, how long had that thing been standing out here? Thirty years, forty? Crikey it could have been here fifty years. We’d found proof of the Hydro Track. This was the route first cut by Charles Gould more than a hundred fifty years ago. Of course we put a couple of our special pink tapes on the sign, made a waypoint, and sent off a Yellowbrick position so that all of you could share in our excitement. Then we headed home. A long trudge lay ahead. But the elation of fulfilling a dream made light work of our task. In fact, the ever beautiful scenery seemed to grow in magnitude as we both savoured the moment.

“Yahoo!” I yelled, alarming Judith. “There’s a Hydro sign.” And rushed forward praying I’d not just imagined it. I hadn’t. Standing tall on a metal stake stood a yellow metal diamond with that familiar red dot in its centre. Geez, how long had that thing been standing out here? Thirty years, forty? Crikey it could have been here fifty years. We’d found proof of the Hydro Track. This was the route first cut by Charles Gould more than a hundred fifty years ago. Of course we put a couple of our special pink tapes on the sign, made a waypoint, and sent off a Yellowbrick position so that all of you could share in our excitement. Then we headed home. A long trudge lay ahead. But the elation of fulfilling a dream made light work of our task. In fact, the ever beautiful scenery seemed to grow in magnitude as we both savoured the moment.

Funny, we were still on a high trudging up another hill through waist height growth when Judith sudden yelped, “There’s another one!” And following her outstretched arm I saw the second diamond ahead on the hilltop, black and backlit by the now weakening sun.

Funny, we were still on a high trudging up another hill through waist height growth when Judith sudden yelped, “There’s another one!” And following her outstretched arm I saw the second diamond ahead on the hilltop, black and backlit by the now weakening sun.

It was Judith’s turn to tie the pink tape on this relic. Her turn also to pose for photos. Beautiful ones they are with the Elliot Range and Franklin River in the far distance.

Suffice to say we got home in a timely fashion, a ten hour day, our feet sore but no broken bones, no skinned shins. Just plenty of wonderful photos and glorious memories. And a few ideas of where to go next time.

Fulfillment

Packing up and walking out the next day turned out to be another marvellous experience. What can we say? The work we had completed to give ourselves the opportunity to experience such greatness really sank in. And the walk down The Huon Way, now cleared by others inspired by our work, is a magical jaunt through one of Tasmania’s most stupendous forests. Treat yourself. It’s easy and safe, walk The Huon Way from Sir John Falls past Camp Twin Pines to the end of the shoe road. Now, wouldn’t it be wonderful if Parks were to put up a few of those informative signs describing the various species and some of the history.

LOCATION MAP Produced using the GPSU Program You can find all the information about GPSU on www.gpsu.co.uk.

Dear Jack and Jude! Just started following your blog. Very nicely done! You are fantastic writers! What beautiful exquisite pictures. Thanks for letting us follow your journeys! Regards Chuck

Very much appreciate your kind words. This area is dear to us and our passion helped produced a good blog. Next one will be as good we think.

Hello Jack and Jude, What a wonderful read your latest blog is! I have a fascination for the Gordon – Franklin area and even though most of it is from the air, I appreciate the scale and difficulty of your expedition! Such a beautiful place. I look forward to the next installment. Regards Geoff.

Thanks Geoff, be good to see you again like early last year at the Sir John Dock. Amazing that we actually got to explore that buttongrass plain you photographed for us. A bit taller stuff than it looks in those photos!

Hi you guys

What an exciting life you lead I love reading about your exploits.

Love to you all

Diane and Kevin in the UK

When we read of the devastating rain you’ve had in the UK, we thank our lucky stars that we had such perfect weather when on the track. In fact we’re beginning to think that global warming is making Tasmania the new Gold Coast!

Hi J&J

Thank for the latest. I enjoyed reading the blog and join you on your excursion through the Bauera bush. You certainly take on some challenges.

Nice pic of Jude relaxing looking the picture of health and one of Jack looking totally pooped (well done for showing that one).

Margaret Muir

Hello Margaret, So glad you enjoyed our little outing. Such good fun and hard work of course which one day may mean others will be able to follow our tracks and take in the wonderful beauty of Earth

J and J