July 2015 June 2015 >>

Blog of Jack and Jude

explorers, authors, photographers & videographers

Love for Wilderness Afloat and on Land

First we were a young family sailing around the planet enjoying a truly wonderful experience that everyone should have.

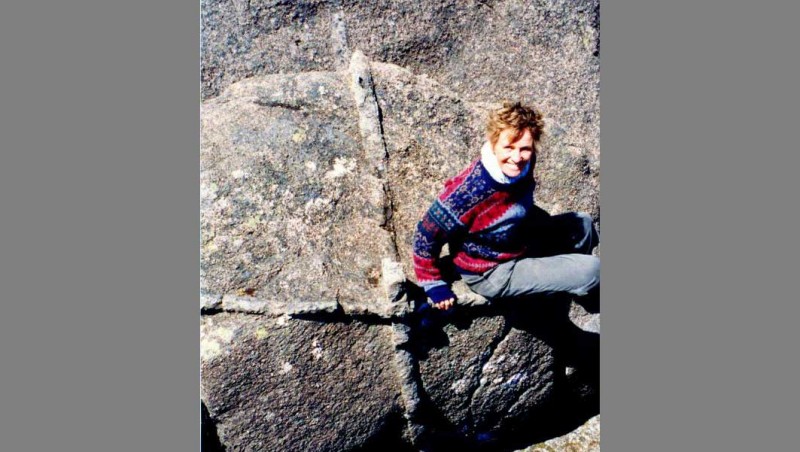

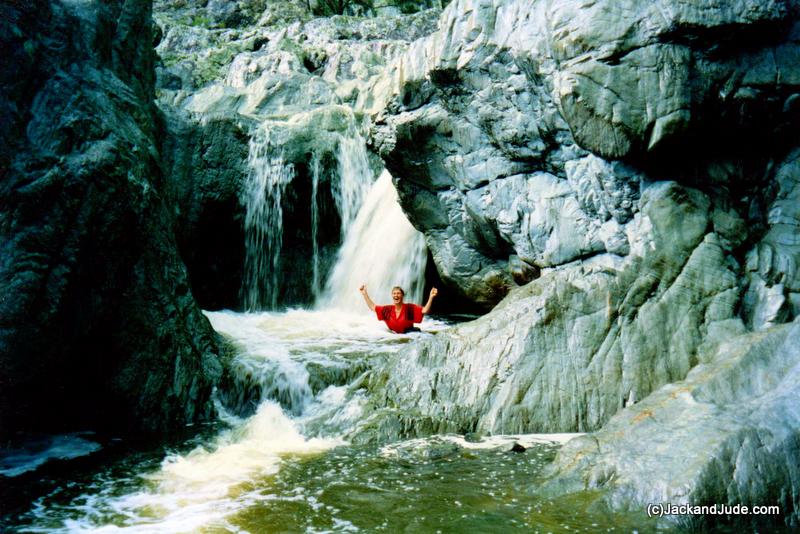

Wollomombi NP 1994

Then the time came for us to swallow the anchor to secure our future, and after that we sorely missed Nature’s majesty and the challenge of finding our way unassisted. So we took up trekking the wilderness to fill the void.

A strangling fig wrapping around a host tree that it will eventually devour

While this website mainly covers our adventures since re-launching the good ship Banyandah in 2007, I’d just like to reminisce and have put up a few photos covering some of the walks we took during the period chained to the land earning freedom chips. A wise word, especially to our younger readers, is that one of the greatest joys of NOT becoming a couch potato is you’ll have plenty of memories – both good ones and the not so good that will amaze you as your fine bodies fail. So, if you have a few moments, sit back and take a look at our photos and imagine conquering mountains and crossing seas. It is possible. We believe good karma helps, which is easily gotten by always being kind to Earth and her creatures. But be aware. You must be prepared to look after yourself. Really prepared. Otherwise Nature will find you lacking.

Nearly Two Decades Land Bound

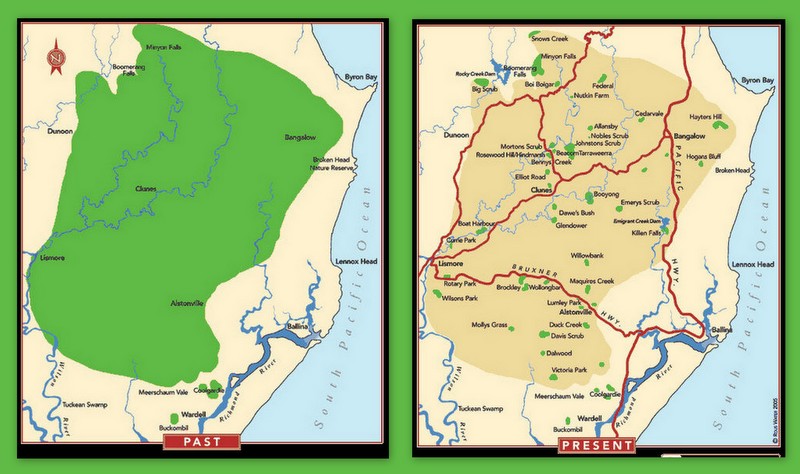

Through that nearly two decades of being land-bound, Jude and I extensively tramped through much of the Forestry lands and National Parks of northern NSW and SE Qld. That’s something we still do in our time away from Banyandah. The Great Dividing Range occupies much of that territory, while the largest continuous expanse of subtropical rainforest, “The Big Scrub” once flourished across 75,000 hectares.

The Big Scrub almost all gone in 100 years

The Big Scrub extended from the coastal plain inland from near our house at Ballina to Lismore in the east and to the edge of Meerschaum Vale in the south to the Nightcap, Goonengerry and Byron Bay in the north. But after broad scale land clearing by cedar getters and settlers that began in the 1840’s, only about 300 hectares exists as tiny remnants today. That’s less than 1% of the original forested area in existence before white man entered the land where the Bundjalung Nation hunted and collected rainforest bush food.

How Our Bush Adventures Began

Shortly after moving ashore, at a party on a farming commune behind Mullumbimby, while gazing over the thickly forested hills we asked our host if it were possible to walk through the forest to the small village of Nimbin.

“Of course you can,” came his immediate response. “There once was a well used track along the ridgeline. Interested?”

Well, we are always interested in Earth adventures, so before another hour had passed we found ourselves sitting on the veranda of a friend of our friend, a large cardboard box filled with rather worn topographical maps on the table before us.

Well, we are always interested in Earth adventures, so before another hour had passed we found ourselves sitting on the veranda of a friend of our friend, a large cardboard box filled with rather worn topographical maps on the table before us.

When the one for that area was spread before us, we immediately became entranced by the many faint contour lines showing ridges and valleys, streams and ponds. Then in a few minutes under this man’s tutelage, we learned the basics of how to read a topographical map and the meanings of the various symbols. And because we were sailors with wide practical experience that topographical map, like a sea chart, immediately presented a picture of adventure.

On the porch around us were touring bikes and a couple of well loved kayaks and climbing ropes hanging on hooks, all indicating that this man took his adventures seriously. Good, I thought. He’ll know his stuff. Naturally, one of my first questions was, “Where’s the most exquisite location you’ve explored?”

Washpool and Oorooroo creeks

He didn’t need to think twice before answering, “Inland from Grafton there’s a valley so steep and so hard to access that machinery has never entered it. The old growth forest found there is pretty much as it has been since the Mt Warning volcano cooled and eroded millions of years ago.”

Reaching into the box, his fingers easily found a particularly tattered map. When opened on the table, we noticed that tape held the folds together and that the margins were scribbled with notes.

“The Washpool Creek flows through this valley with several feeder streams coursing down both of its flanks. This one,” and here his fingers followed a tiny blue line, “is the Oorooroo Creek. It’s exquisite. There are waterfalls and shear rock faces covered in orchids, mammoth White Booyongs, Australian Red Cedars, Black Bean, thick vines and giant palms.”

Smiling broadly at the vision, Jude yelped, “Yeah… I like it. Where do we start?”

Sagely shaking his head he said, “Look, maybe it’s best you leave that one till you have more experience.”

Meanwhile I’d noticed a few notes on the map indicating a route and starting point, so I charged straight into something basic and essential. “Tell me, how do you navigate in thick forest? Do you count ridges and valleys or only follow creeks?”

Alarmed at my question, our host immediately began folding the map, saying, “Do not go into the Washpool. You’ll only get into trouble.”

Now those were the days before GPS navigation, back when navigators used compass bearings on headlands and peaks. We also used dead reckoning to keep kept track of direction and distance travelled from the last known point.

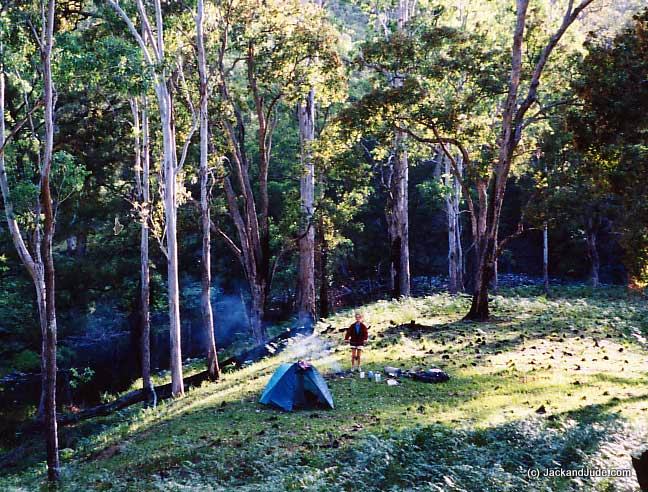

On the way back to the commune that day we bought the local topographical map, and the next day Jude and I set off to walk to Nimbin on what we had learned had been the track used by the early postmen on horseback. What a marvellous experience. As soon as the developed world slipped behind the veil of lush forest, peace and serenity enveloped us, and like little kids, new wonders stopped us every few feet. Then that night after finding a small clearing alongside a trickling stream, we relaxed around a crackling fire feeling grand to have used our bodies while overwhelmed by the starry night sky and strange silence interrupted by even stranger sounds.

On our way home to Banyandah, which was then standing high and dry on bare land, we bought a map of the Washpool Valley and studied it for the next two weeks while the moon waxed to half full. Then we drove off to find the starting point I’d noted on the fellow’s Washpool map. Of course that first trek was arduous, horribly so, but we found trekking wilderness to be very much like cruising in a vessel. Carrying our house with us, no matter what happened during daylight we had a place to rest at night, and it fulfilled our need to be self reliant while also filling our memories with achievement and glorious Nature. That said, we also discovered Lawyer Vine, commonly know as Wait-a-While that tied us up like razor sharp spider webs. It sends out lots of slender barbed tendrils that seem to reach out to grab our arms and faces and clothes, holding us back lest we slash our skin. The patience we’d developed while sailing oceans proved mighty helpful.

Twenty Five Years of Trekking

Once we had built our house and work shed, we earned a crust fitting out a few boats in the dying days of local ship building.

After that collapsed we evolved into making timber kitchens, stairs, libraries, and the like, in our two person business where I made the pieces and Jude did the finishing. As we were rebuilding Banyandah at that time, with our workshop next to the house meant we worked long hours, often seven days a week except for family gatherings or equally important events. To sort of recharge and clear our lungs before starting another contract, we developed the habit of going bush upon completing a job. In that way, after exploring all of the Washpool Valley over many visits, we tackled the subtropical forest of SE Queensland.

Creating a Reason to go Bush

Being in the timber business, we naturally loved wood and trees, and knowing of the rapidly dwindling supply of good cabinet timbers, we joined forces with about a hundred others and formed a group called the Subtropical Farm Forestry Association to encourage Big Scrub land owners to plant subtropical timbers. I became its first president and that meant I needed a greater knowledge of the many varieties of cabinet timbers native to our area, creating another reason to go bush.

But we sort of got worn out after a decade of pushing through thick, wet, subtropical rainforests identifying tree species. It was darn hard work that often left us bleeding from our arms and faces. About that time the endeavours of our farm forestry association to find farmers willing to plant cabinet timbers found opposition from State Forests who needed more land for eucalypt plantations. They were offering joint ventures that paid land owners maintenance fees and an earlier harvest income. You see, eucalypt mature in about ten years while rainforest species take at least thirty.

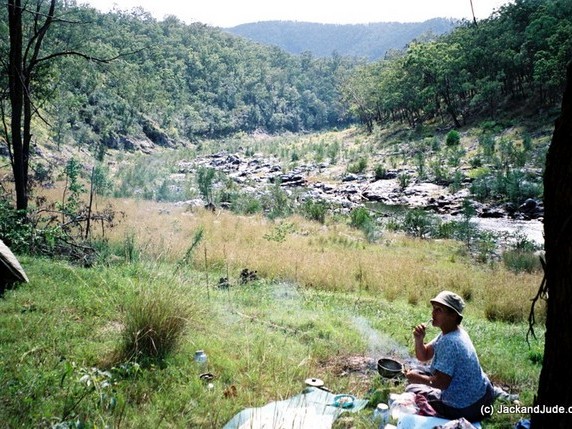

So we began walking through open, dry eucalypt forests. They are much easier to get about in and much more fun because we could cover heaps more distance under an open sky and have starry nights. But we lacked a mission to motivate us like we had before.

Aussie Bush History to the Rescue

In the late 1800s through to around 1950, the mountainous area inland of Grafton had seen much mining activity. In the ten years walking rainforests, we never saw another soul, but in the first year trekking the easier dry forests, we met a man and his son, and a local rancher on horseback. That happened when we were down in the Cooradoral, a small creek that flows to the Mann River just south of the Gwydir Highway connecting Grafton to Armadale. There’d been a fire in that forest a few weeks earlier, a hot one, but where we were camped was rich and green when this lanky fellow rode up with his three dogs sniffing all our stuff. In our conversation he mentioned that the fire had burnt away all the weeds from Cherry Tree Creek, exposing the long lost gold mine. Hearing that, our ears perked up. Three days of walking later we reached that creek and were astonished to see a large boiler sitting atop a pile of river stones. A closer inspection revealed bits from a Huntington Mill and an ore stamper, and after exploring further up that creek we discovered a brick smelter and footings of a house along with rails and trolley wheels.

All of a sudden we’d found a new reason to go bush and that began a five year search to not only document the remnants, but what we also wanted to learn was how those early settlers got that big, heavy boiler into that river valley. It didn’t get there on a barge. There’s not enough water in the river that also tumbles over several falls. In many searches we trekked up and down every ridge and skirted the valleys looking for scars that could have been made when hauling in such a heavy load. Naturally we passed our discoveries on to Parks, and were eventually asked to lead in a scientific team to catalogue and record the site. After doing that, they asked if we could locate some of the abandoned underground mines. They’d supplied an approximate location based on the claim, and we’d go off for a week to scramble up and down slopes finding quite few. Most were dangerous holes covered by regrowth, a trap for the unwary. In one we found a dead brumby; another had the remains of a cow. While doing this, we also found and documented a shed containing a crosscut saw, an axe, and other paraphernalia. In another location we found the remains of a homestead with piles of fencing and a rotted water tank.

All of this kept us occupied until we’d finished rebuilding our boat and had won enough freedom chips to close down our shop so that we could go sailing again. Our plan; to sail to unique locations then trek inland. This blog records several of our excursions in northern and western Australia and we’re now heavily into the challenging forests of Southwest Tasmania.

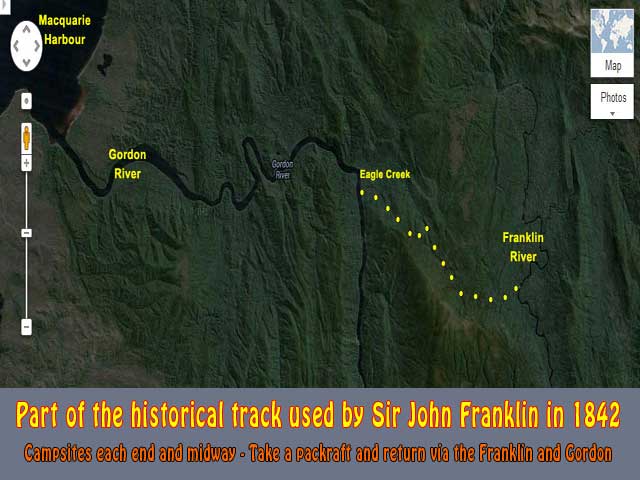

Now for those seeking a fabulous challenge that is doable for the less experienced, we suggest hiking the Eagle Creek track that connects connecting the Gordon to the Franklin River, which a group of us cleared it a couple of years ago. Originally cut in 1842 to take Governor Sir John Franklin and his wife Lady Jane to see the west coast (details here), it is the most intense rainforest we’ve ever encountered, and it’s mixed with open button grass plains that commands grand views of the stark South West mountain ranges. To add more adventure, take along a pack raft to complete the circuit by paddling down the Franklin to the pick up point at Sir John Falls on the Gordon. But please remember. This is more than any walk in the park.

How to organize? The man to talk to is Trevor Norton, master of the Stormbreaker, which does upwards of forty trips up the Gordon River a season, right past you’re departure point. Trevor knows this track better than anyone and he’s not only a very nice person, he is profoundly knowledgeable. He will tell you everything about your challenge, take you to Eagle Creek, and arrange to pick you up. Trust him, we do. In the world of extreme adventures, Trevor Norton is your man.

Walks/Treks:

Duffer Falls

Cooradoral Valley

Eagle Creek