March 2016 February 2016 >>

Blog of Jack and Jude

explorers, authors, photographers & videographers

The Great Escape

Chapter 1 – Strahan to Pyramid Island

Chapter 2 – Pyramid to Bond Bay

Chapter 3 – Carver’s Boatyard

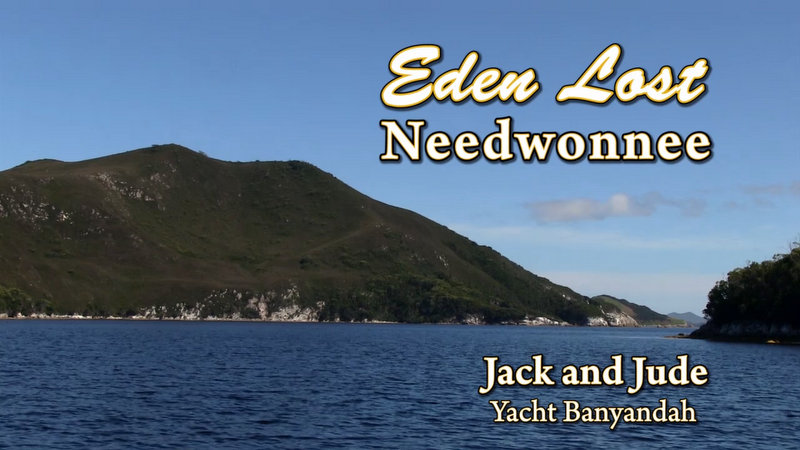

Chapter 4 – Eden Lost Needwonnee

Chapter 1 Strahan to Pyramid Island

There we were in Strahan. We’d completed our mission of finding and tagging the lost historical Goulds Track through wet forests to the open plain below the King Billy Range. We’d made a whistle stop tour of our favourite Macquarie Harbour highlights, had dinner parties and enjoyed great times with our dear friends, and been loaned their vehicles to tour the hinterland to see the shockingly low water level in the lakes that supply the power plants. Then thought how amazing that a string of events can unravel man’s best laid plans, putting Nature in a horrible corner to survive or die.

In a word, it was time to get on with our other plans for the summer.

South of Strahan at Port Davey lived one of the world’s least known people who, in our opinion, epitomize harmony with Earth and quality of life. The Needwonnee clan peacefully enjoyed a close family life amongst startling beauty for an unbelievable thirty-five thousand years. An amazing achievement when we remember that Christ walked the earth just two thousand years ago. Their record run of harmony disastrously ended when white man invaded their island.

Jude and I wanted very much to witness and record what remains of their culture that was wiped out in a few short years just two hundred fifty years ago. Also in mind was to find a boatyard that once existed near the Davey River next to stands of Huon Pine that were logged in the latter half of the 1800s. We get our kicks using our skills and craft for worthwhile projects. Helps keep our minds active and team spirit strong.

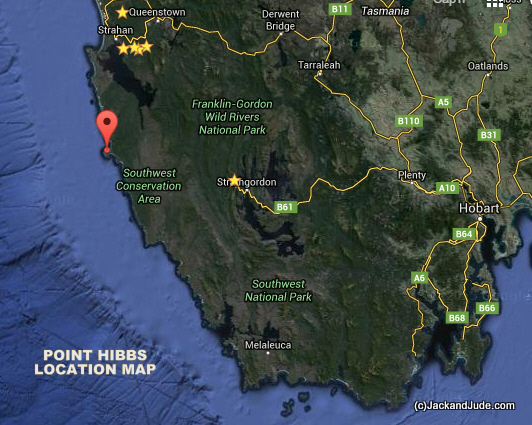

Ever since we helped Garry Kerr bring the Jane Kerr around to Strahan from Hobart after last year’s Wooden Boat Festival we’ve a had strong hankering to explore the west coast around Point Hibbs. He’d taken us into an open roadstead used by professional fishermen, where we saw not only a beautiful area rich in history but also an anchorage behind the aptly named Pyramid Island; tolerable in moderate S/SW weather. This anchorage could break up the usual long overnight passage Strahan / Port Davey.

On Tasmania’s West Coast the weather dictates our every movement. Even in summer when the pressure systems are less intense and move more slowly, it’s still essential a weather eye be kept sharply focused. To do otherwise would be courting discomfort and disaster. Therefore when the weatherman forecast an ideal situation for heading south to Point Hibbs, a light nor’westerly followed by several days of calm, we announced to all that the good ship Banyandah would be leaving Strahan after a full year in her calm, nearly landlocked waters. This signalled a fury of activity. Dinner with friends Trevor and Megs lead to another on board Banyandah with their deckhand Rob, our neighbour from Songlines. Of course there was plenty to do. Engine work proceeded in between the disassembly of Sir Aries to find and fix a hard to find gremlin that had him stick and steer erratically, both frustrating and dangerous in following winds. Wind vanes must be loosy-goosy to have light wind forces operate the steering rudder and Sir Aries wasn’t. This magical device, invented in the 70s by Nick Franklin on the Isle of Wright, suffers over time from the alloy in the leg expanding, tightening the plastic bushes holding the rudder shaft.

Trevor and Rob went off up The Gordon in Stormbreaker for a rafter pick up trip, leaving dockside for our use a 4WD. We chucked in our gas bottles for refill, then filled her up with a trolley of fresh food, a couple of blocks of beer and boxes of Jude’s favourite wine, before stopping to say so long to a few more of our very fine west coast friends. This got us back to Ronnie’s dock as the sun cast a golden hue across Mill Bay where Banyandah looked like a Chinese laundry, Jude having earlier made good use of the shore water. By the time all that was folded and put away along with our supplies for several weeks, we had only time for a quick bite before pumpkin time sent us to bed.

Next morning, Wednesday the 10th of February, I awoke like a bull released out a gate. The forecast light nor’westerly was nowhere about in the thin mist. But with Point Hibbs forty-two miles away, including nearly fifteen miles inside the harbour to the narrow channel passing through Hell’s gate to Cape Sorrell, we didn’t dally. We’re purist when it comes to sailing, and because Banyandah isn’t one of those sleek thoroughbreds that race across the ocean means for us a head start is best or we gamble on a late arrival or having to use our engine which is noisy, stinky and spoils the mood.

In cool misty rain Jude scurried along the jetty releasing our lines while I’m nudging our lady out backwards. Once I make her a morning cuppa, Jude’s a little demon and worked energetically to clear away fenders and mooring ropes before demanding to take over the helm.

Getting back late to the jetty meant we were sorry not to have seen our mate Ronnie for farewell hugs. He owns the jetty and the Wilson Pride, a very fine Huon Pine work boat, a genuine nice guy possessing a wealth of knowledge on a great many things including the harvesting of Huon Pine. As we motored along past Regatta Point with the small town behind it still mostly quiet, we chatted with him about this and that and made the promise that we’d be back. The West Coast folks are tops. Friendly, helpful, trustworthy, and in an everyday way, smart. We’re very fortunate to have become involved in their small community.

Now! Not having been outside in a year struck us the moment we entered the channel and were confronted by the beacons marking the shoals vaguely visible in the poor light. But our girl almost knew where to find the gate, and soon we were out back in the rollie stuff with a two to three metre swells running up from Southern Ocean storms.

Jude still at the helm made me head photographer, and I clicked many happy snaps and while still in contact sent a few to family and friends around the world via Instagram. Outside we rolled about, our fully raised mainsail helping to slow our back and forth rock. With so much new stuff on board, bottles clinking, things falling over, Jude needed to rush below to sort out so I shaped a course wide of the coast to minimise the backwash. Into deeper water smooth out the swell plus I was rewarded by finding a light breeze, enough to shut down the donk, and immediately felt the bliss of silence. Our early start allowed us to doddle along, relax, and reflect on our achievements and happy times in Macquarie Harbour. Our phone still had a link to a tower via our broomstick antenna and Jude chatted with her boys while Sir Aries miraculously steered a sweet course down the coast in the light conditions. In a single word it was Heaven.

In addition to being sail crazy, we’re also hunter gathers, believing if managed correctly, this good Earth can provide ample to sustainably supply all its creatures’ needs. Jack and Jude take only what we can eat. We don’t run big freezers that need to be filled. We only have a very efficient small fridge and Jude bottles the excess when we land something too big for a few meals. The moment we hit blue ocean our fishing lines were laid out. Near the shore after Hells Gate we tried our squid jig on the advice of Robert and Carol who have snagged a couple of tasty squid from their tinny along that craggy run. But having no luck, out in the deeper waters, our trusty jig that had laid dormant the last year was let out.

Sailing miles is often a non-event of letting Nature do its thing while we humans get ourselves as comfortable as we can and occupy our time. Jude dove straight into bringing her logbooks up to date while I lay down to conserve energy and be more ready for what lay ahead. The day warmed and the north wind strengthened till we were romping along at a respectable five knots that had me concerned that our Point Hibbs open anchorage would become untenable. Guess I’m a worrywart of sorts. Nature will prevail, and we’ve learned over the years that we’ll cope. But my active mind likes to play out all the possible scenarios and be as well prepared for any eventuality.

Excitement arrived just after noon when our trolling line snapped bowstring tight. “Hope it’s not a stinky barracuda” was my first thought. But this one ran deep signalling it was a big tuna. I used to battle these brutes straightway when I was young with good shoulders that didn’t snap tendons. But now I let anything big tire before I start hauling in. This one I let run after us for maybe half an hour before taking up the handline from my steady spot leaning back against our liferaft. It’s odd this battle between man and beast – primeval emotions are aroused as if we’ve been hardwired as hunter gathers and providers of sustenance for our families. Sure, some of you will think it cruel. But much of life especially that associated with mankind is far more cruel without reason. We maim and kill great numbers in vendettas and religious disputes; so providing food for our table isn’t so bad. Besides it’s cave man stuff that directly links us to mother earth, and if Earth had a big sustainable supply, much of the stigma associated with killing a wild beast would evaporate.

In the contest involving Jack and Jude against Mr. Yellowfin Tuna weighing in at around fifteen kilos, as we continued sailing along we won in an exhilarating climax that saw the brute hefted over our side railing into our cockpit where I swiftly dispatched it to tuna heaven. After I bled the creature and cut away most of its edible meat, its carcass went overboard where it would nourish many thousands of other animals. That’s one thing for sure. The oceans are spotless – except for man-made waste. After we’d scrubbed up the mess and gotten rid of the fishy smell, Jude bagged the meat and then found room in our fridge to chill it.

So far it had been a magic day. But the forecast light winds were now becoming a bit worrisome as Point Hibbs quickly approached. Visions of being forced to carry on down the coast overnight danced round in my head and I could imagine the wind dying out at night leaving us bobbing about like a toy boat in a bathtub with miles to motor. With three hours of light still remaning we decided to chance it, and in we went, shortening our headsail while rounding Pyramid Island to the east. With the headsail away and our engine ticking over we were delighted to find a patch, which although active with some small white wavelets rushing through, was worth a closer look and we furled the mainsail in rather rollie conditions. Deep water ran right close to the amazing rock island jutting out the sea. Kelp beds swished back and forth in the surge along its shore, but a hundred metres off, through fairly clear water the bottom appeared to be sand, so the anchor was sent down to test the bottom.

The Manson Boss dug in sweetly, pulling us around abruptly to face the wind and approaching swell, and we thought this will do nicely – so long as the wind doesn’t pick up. The big south-west Southern Ocean swell now hit the island and swept past its northern end. Some of it wrapped round, sending us up and down, but we reckoned the wind would ease as the sun set, so we settled back to observe the awesome new scenery with a cold one to celebrate our success.

Chapter 2 – Pyramid to Bond Bay

The weatherman’s forecast proved correct because as the sinking sun began to burn fiery red behind the conical Pyramid Island, the breeze faded, and as it did the plaintive squeals of a penguin colony replaced the sound of wind. The sea took longer to settle and the Banyandah still rocked, so at bedtime I took my pillow and marched forward to throw a settee cushion onto the cabin sole next to our mast. I jammed myself in tight with a few large cushions and lay there listening to our flightless brethren jabber on, wondering what amazing stories they might be telling their neighbours. Gratefully I slept well. Jude too. She can tolerate more motion than I and had slept as usual, athwartships across the aft cabin double bed.

The weatherman’s forecast proved correct because as the sinking sun began to burn fiery red behind the conical Pyramid Island, the breeze faded, and as it did the plaintive squeals of a penguin colony replaced the sound of wind. The sea took longer to settle and the Banyandah still rocked, so at bedtime I took my pillow and marched forward to throw a settee cushion onto the cabin sole next to our mast. I jammed myself in tight with a few large cushions and lay there listening to our flightless brethren jabber on, wondering what amazing stories they might be telling their neighbours. Gratefully I slept well. Jude too. She can tolerate more motion than I and had slept as usual, athwartships across the aft cabin double bed.

Next morning I awoke as if floating inside a warm cocoon. Poking my head out, through sleep glazed eyes an Egyptian Pyramid dominated our scene. Coated in straw coloured tufts it looked like a strange furry creature.

That morning we clapped our outboard onto Little Red and after a slow fly past the island’s kelp beds, we took courage and headed across the gap towards a sandy bight on the mainland.

Just before the Second World War, the Nielsen family had explored the Spero River that lies south around Point Hibbs, finding enough Huon Pine to make it worth their while to establish a camp upstream on its banks. Felling the trees and getting them down river was only part of this difficult task, getting them to market was another. They couldn’t be taken overland, but only by sea, up the misty west Tasmanian coast. They first tried to link them in line to lessen drag and tow them by a tiny craft with a big heart. The Wy Wurry was often used to bring supplies to the men working the Spero. Back in Mill Bay, the Wy Wurry had been our neighbour, a craft you’d look at once and think it someone’s calm water weekend fishing smack. But inside beat a giant heart and that craft had towed logs back to Strahan by the route we’d just taken. She often sheltered in a tiny cove opposite Pyramid Island hemmed in by rock and fringed with yellow sand. The Nielsens had used explosives to make a narrow entrance, and we were on the hunt to relive the life of our unpretentious stable mate, the Wy Wurry.

This may sound like fun, but ocean swell meeting shallow water can rear up to become an unpredictable beast that when near craggy rocks can prove fatal. We navigated the open gap to the mainland just fine, rising and falling gently, but finding the pass and negotiating its slanted entry proved so challenging we were very impressed with the skills of those early boatmen.

Remnants of a fishing camp were found behind a beach strewn with man’s refuse which made us mad. Middle of nowhere, no towns for miles and yet there were drink bottles, old shoes, lengths of rope, and lost floats littering what once was a pristine beach. We’ve seen this before. No matter how remote, every beach, every rocky shore has man’s litter. Amongst this trash lay abalone shells and pretty polished stones as well as the remains of a once mighty albatross, the world’s biggest flying creature and master of violent oceans. Its massive wing, more than a metre long, still held some feathers, but it was its lightness that intrigued us and so I propped the wing’s main bone between two rocks then stomped on it with my boot. It didn’t break with my first wack, so I gave it a good thump using my weight. Poor thing! Terrible way to treat a king of sea and sky, but our scientific experiment showed its amazing construction. Such a strong structure for just a 10 mm round bone that was hollow with a wall of maybe 2 mm thick. Nature is truly magnificent and should be cherished. It surrounds us with greatness that’s far beyond our comprehension, so we should be treading more lightly with greater reverence.

In the following days, the sea became an electric blue platter with calm sunny weather perfect to journey across to the rocky shores of Pyramid Island where landing proved another challenge. The boulder beach with its surge over shiny wet rocks looked ready to twist an ankle, so we choose a cleft in solid rock and went in on a swell. Without the outboard I back rowed to let Jude step ashore at its peak. Then a little manoeuvring got me into the cleft where, on the next surge we lifted Little Red out of harm’s way.

Walking atop those rocks sent powerful impressions to our souls. Deep ocean blue surged into rocky canyons, foaming to brilliant white and swishing the gleaming orangey forests of bull-kelp back and forth, over and over again. Nature at work, ceaselessly, every minute even as I write. We were humbled and uplifted at the same instant knowing a greater power than ours rules Earth. And when we realized that mankind’s greatest power is designed to destroy and kill while Earth’s magic only endeavours to build and provide sustenance, it made us think that we’re heading in the wrong direction.

Those straw tufts we’d seen were riddled underneath with tiny burrows and narrow paths worn smooth by the large colony of penguins that went to work every morning and came home each night, nodding and greeting and chatting. Oh! How I wish that one day our children will hear their stories; what amazing tales they’d bring to enrich our existence.

ST 967 HIBBS PYRAMID

42 36 16.4886 – 145 16 34.6106 – Height 70.6M – AGD 1994

Surveyor General says ours is first recorded visit since 1976 !

The weather people had been telling us that our window would soon be closing with a cold front racing up from a storm bringing a whip of northerly winds. We listened twice daily, tracking its approach, wondering if it would come as forecast in the middle of our fifth night or if we’d be lucky to see it strike at daylight. That last day was hot and super still, perfect to climb to the top of the Pyramid and survey miles of our world. We saw smoke billowing from three separate fires with flames destroying untouched bush land so very tinder dry. Tasmania has just come through her driest autumn and summer ever. We cringe every time there’s lightning, but their hadn’t been any, so we’re thinking spontaneous combustion might be the culprit. Climate change. It’s here now, and increasingly devastating in many ways in the decades to come.

That last night, back on my cushion next to our mast, we danced to an awkward ripple, a harbinger of things to come. I lay listening to the penguins and imagined them chatting about the approaching weather. Having endured it since birth, I bet they could tell us when it would strike. I heard our ships clock ring out the hours, and also heard the first moaning of the wind. At midnight I popped up to feel a ten knot northerly breeze and saw how still we lay, so went back below, set the alarm for five, then tried valiantly to nod off to sleep. But I just couldn’t relax in an open roadstead with stronger winds coming. Every swish sent a jolt through my brain. This sailor has had many sleepless nights and fortunately I’ve developed the knack of getting rest without actually sleeping while keeping tabs on my boat.

Just after the first bell of the new day I started feeling a tad uneasy. Outside might still be OK, but I didn’t feel right on what quickly could be a lee shore, and thinking we might as well be at sea making miles than me on the floor fretting, went aft and turned on the cabin light. Seeing Jude snoozing soundly gave me second thoughts. Lucky gal. But I woke her. She doesn’t mind. It took a few good shakes to rouse my lady, then I went back to make us a hot drink. Jude never grumbles. She just gets up and on with it, a true sailor who accepts the hard that comes with the great. Hey maybe that’s part of mankind’s problem. Too many want an easy nondescript life, increasingly shutting out the real world and becoming disconnected to Earth. With that comes disrespect. Earth’s other issue is too many of us.

By the time we’d gotten going, engine running, deck lights blazing, the sea had risen with the bigger ones slapping spray over our bows. Having had plenty of practice, we concentrated on communications as Jude drove Banyandah forward into the inky dark night while I’m up forward controlling the anchor winch. It’s a tricky business not to run past the anchor and be pulled back maybe becoming side on to the marching soldiers. So I use a hand held torch to watch the chain and signal Jude its direction. She’s become good and I’ve become patient, so out of the depths we retrieved our precious Boss anchor, stowed it then I rejoined Jude. Thankfully modern gadgets make getting away from dangers a much easier task than years ago when I’d still be on deck, all lights extinguished, searching for white breaking water instead of following our progress on our chart plotter in the relative quiet behind our dodger while Jude followed the line that the plotter made coming in. Nevertheless I still popped forward to ensure the dang thing was correct, but even that’s easier because I knew exactly where to look to find Pyramid’s dark shape.

We did a big loop to gain a little sea room then raised our mainsail, pulling in a single slab reef knowing the wind would only get stronger, then flew past Point Hibbs bound for Port Davey 65 miles south. Unfurling 70 percent of our headsail, Sir Aries was engaged, and by 3AM everything was so sweet I gave the deck to Jude and went for a sleep.

The forecast had indicated 15 to 25 knots reaching 30 knots in the morning. Storms often build over many hours and are quite exhilarating when young and the wind isn’t gusty, the sea still easy without much power. When I popped up about seven I was delighted that we were creaming along making sixes and sevens under a leaden sky. Towards land four miles away, the Low Rocky lighthouse still flashed with bright fishing boat lights like small towns between us. We hot bunked, Jude taking my warm bed, leaving me to watch the Mutton Birds and Albatross soar across the breaking swells in their search for schools of bait fish. With wings spanning over two metres Albatross’s are renown for soaring miles without a wing beat. They’re masterful fliers along marching lines of wind swells, swooping upwards then back along another. We find they often soar past to give us a look with their beautiful eyes. Wandering-Albatross have mascara highlights above their eyes that may have influenced early women to beautify themselves.

Our tuna supply had been severely depleted so I plopped our trolling line back in, thinking, yeah right, you’ll be lucky, while also questioning the wisdom of trying to catch a big beast going fast in building conditions. But the aforementioned hunter-gatherer within me made me do it.

The hours ticked by, the gusts got bigger and we went faster, rolled more, and lost a little more control. Sailboats can be easily overdriven. Their speed increases tempting us to hang on a bit longer. Poor Miss B laid over, dipped her shoulder, corrected, then fled down the next swell and repeating the whole process, becoming more wild and less under control.

With the wind dead aft, in the wilder off course runs our mainsail back-winded a few times, causing me to think about lowering it and raising our forward staysail. Best to pull a boat in heavy conditions with sail forward than to push it with sail more aft. I didn’t wake Jude. Should have. I didn’t get my harness either. Probably should have done that too. In my younger years I was the prince of our forward deck with cat-like feet and hands like talons. I could dance changing massive sails, impervious to the leaping deck. Course I’m a bit older now, not so cat-like, but I’m thinking I’m smarter now. So, in a very decisive plan, I started dropping our mainsail, but the filling of the drooping yards of cloth sent it around our stays, tilting us over while the cold blue sea rushed past my feet. Patience again proved the winner. Timing the downwind runs, handful by handful I brought that beast into its stall and had just about lashed it down when the aft cabin door crashed open and an angry Jude demanded, “Why didn’t you wake me?”

Yes! Why didn’t I, thought I, remembering the mess of sail I’d created. But instead said, “The main back winded and a batten caught in the cap shroud. At first I was just going to lower it a bit to clear the batten. But that didn’t happen so it all came down in a mess. I’ll raise the staysail instead.”

Jude looked up at the lone sail flying, then looking to the sea said, “Why? We’re going fast enough and we’ve got all day.”

Hmm. Right again. Why do more work than you have to with the weather still building? Just then my cheesy grin vanished when our trolling line snapped tight. She looked at it then to me. “Really! You’re a sucker for punishment in these conditions. Aren’t you?”

If the first fish battle was hard this one racing along touching seven knots took a Herculean effort. A twin sibling of the first refused to play nicely once it saw the back of our boat and I kept having to give what I’d won every time it took flight. All during this battle the treble hook held and the line didn’t break, so for a second time that week we had a monster fish alongside waiting to be hefted over the railing. The beast slid back and forth across our cockpit floor making it harder to clean but yielded the same results; heaps of fresh tuna for the coming week.

As the clouds grew angrier, the wind started blowing the tops off passing waves and we were pleased we’d not raised the extra sail. Now close before us rose mountains like no others. Forming an eerie backdrop to the angry sea were sharp peaks devoid of forest but sprinkled white where quartz broke through the coating of button grass. First sighted by Abel Tasman in 1642 they were recorded by Matthew Flinders with George Bass in very similar conditions aboard the tiny Norfolk when they circumnavigated Tasmania to prove it was indeed an island. Flinders perceived a considerable opening and wondered whether they should chance going in, but decided instead to maintain a safe distance and round South West Cape noting the mountains are the most stupendous works of Nature ever beheld.

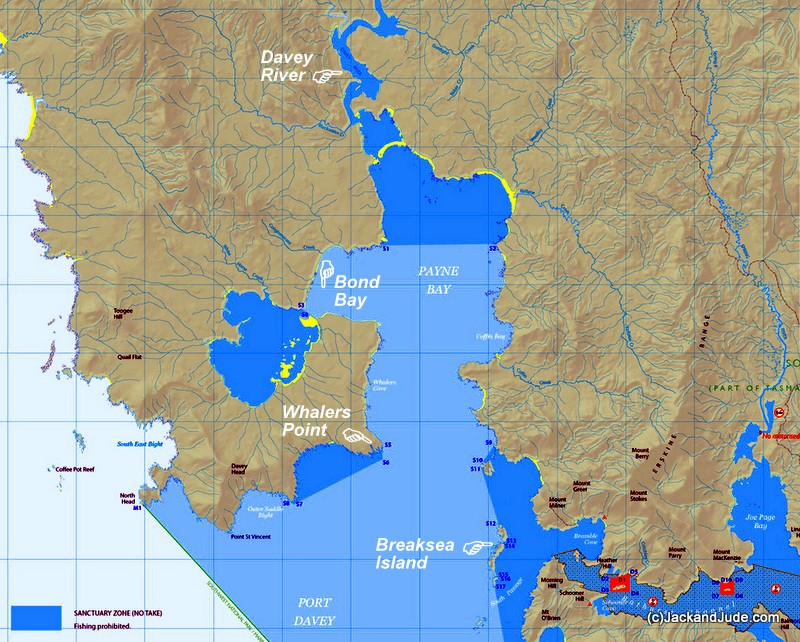

Little was known of the Port Davey / Bathurst Harbour complex until the hydrological/ecology survey of 1988/89. Only small aboriginal clans had occupied this vast area and they were removed after white man took the island in the early 1800’s. For a short while thereafter, a few folk harvested the unique timbers found along the Davey River, but the main of it remained mostly unvisited during the 20th Century. A few mined tin at nearby Cox Bight on Tasmania’s southern shore. One in particular, Deny King made his home in Bathurst Harbour, raising his family along the dark waters of Melaleuca Inlet, and he became so entranced by the unique beauty and rare creatures that he vigorously campaigned for the area to be protected, and largely by his efforts the area was declared a marine reserve in 2005. More on this amazing man can be found in “King of the Wilderness” by Christobel Mattingley.

Little was known of the Port Davey / Bathurst Harbour complex until the hydrological/ecology survey of 1988/89. Only small aboriginal clans had occupied this vast area and they were removed after white man took the island in the early 1800’s. For a short while thereafter, a few folk harvested the unique timbers found along the Davey River, but the main of it remained mostly unvisited during the 20th Century. A few mined tin at nearby Cox Bight on Tasmania’s southern shore. One in particular, Deny King made his home in Bathurst Harbour, raising his family along the dark waters of Melaleuca Inlet, and he became so entranced by the unique beauty and rare creatures that he vigorously campaigned for the area to be protected, and largely by his efforts the area was declared a marine reserve in 2005. More on this amazing man can be found in “King of the Wilderness” by Christobel Mattingley.

Port Davey and Bathurst Harbour are two quite different areas. Whereas Port Davey is exposed to the wild Southern Ocean, Bathurst Harbour is a long estuary, its entry protected by Breaksea Island. Fronting Port Davey are rows of intriguing conical islands looking like sperm whale teeth erupting from the sea, and under headsail alone we drove along them, taking the gusty wind now well on the port beam.

Jude loves these conditions and took the helm while I trimmed sail as we passed Davey Head, tightening up to reach for Whalers Point. Our destination was not the protected waters behind Breaksea Island but those lying north up in Payne Bay that leads to the Davey River where in the late 1800’s a settlement had thrived at its mouth.

Our goal was a small bay halfway up where after the Second World War Deny King’s sister Winsome and her husband Clyde Clayton, another legend of this hard remote area, had a house where they kept their cray-fishing vessel in the shallow waters of Bond Bay. Not so many visit this area, most yachtsmen preferring the safety of Bathurst Harbour. A few kayakers might venture out, and of course the local fishing fleet uses this easily accessible area for overnight stops. Our reason – to search for the shipyard that once built timber vessels there in the late 1800s. A wonderful book on Win and Cylde’s life at Port Davey has been written by her niece Janet Fenton, Deny King’s daughter.

All around us now rose tall peaks that Flinders had described as the most dismal and barren. The eye ranges over the peaks with astonishment and horror. With modern knowledge and technology all the horror has been removed and aboard a stout craft leaves only the astonishment. Having left behind the angry sea after rounding North Head, both of us had sparkling eyes, knowing adventures lay just ahead. But first we must find a safe haven for our floating home.

Beyond Whalers Point, Payne Bay stretched north open to the near gale force winds straight in our face. Cold wind packs more punch than warm tropical ones and these icy blasts were whipping up a short nasty sea down the length of Payne Bay. Best course of action was to start our donk, douse the headsail, and then under good power battle to the quieter waters running close past Whalers Point. Four fishing boats were anchored there. These we passed astern with friendly waves reflecting our delight that the journey was nearly at an end. We’d been battling wind and sea for eleven hours and now that we were out of danger my energy levels slumped. Yet, we faced one last hurdle.

Years ago when exploring Bond Bay looking for Clyde and Win’s old residence, we’d reached the quieter inner anchorage by crossing over a narrow sand bar after passing across a long stretch of shoal. In quiet conditions, this isn’t a danger, but when blowing hard, any error is greatly increased. Passing the last fishing boat we headed towards our start waypoint with breaking white water marking Earles and Curtis Points, the entrance to Bond Bay. Ahead lay a good kilometre of shallow waters close along the craggy north shore with a few isolated patches that must be avoided or a cold night could be the outcome.

Jude had entered our previous waypoints into this new plotter and while I conned our vessel from the windy dodger top she pointed Banyandah as close as she could to each point. It had been four years since our last visit, but a sharp sailor’s eye recognises distinctive features like the rock spur backed by a copse of trees that I’d used as a bearing to cross the shallow bar. Our sounder lost water till we got down to about a half metre under us and Jude asked if she should slow down. But I was confident of my course and could see by the shore that the water was half tide, so I told her to press on.

“Turn a bit left for that copse of trees. Deeper water there.” And she did. Minutes later, with a full metre and a half between us and a clean sandy bottom, I let the Boss go and the wind drove us back till we stretched out the full length of our chain.

Raising my arms crossed signalled Jude to shut down the machinery, then going aft we embraced like teenagers after their first adventure. Gees! We love this life and know how very fortunate we are to have this opportunity to witness such a unique bold creation.

Not wasting time we tidied up, coiling ropes and covering sails that had taken us sixty-five miles from Point Hibbs. Jude loves her statistics. Seems we’d used our engine for 2 hrs, the old Perkins burning 5 litres of diesel, and we’d arrived at noon, most of it under reduced or headsail alone. And perfectly timed to enjoy a lunch of freshly caught tuna steak surrounded by sharp peaks, Davey Head to the south, the Erskine Range to the west and the De Witt Range just on our doorstep ahead. To quote Flinders again, most dramatic and astonishing peaks. We could even spy Piners Peak to the north where forty piners had lived at Settlement Point on the Davey River. Down that way lay our next objective.

Chapter 3 – Carver’s Boatyard

The moment we got the anchor down in Bond Bay, Port Davey the wind swung southwest, blowing icy cold and clearing the weather. For awhile the stark scenery popping out the sharp clear sky kept us in the cockpit admiring nature’s beauty, but after drinking our fill and starting to feel the chill enter our bones we ducked below to cuddle up in bed with the doona pulled to our chins.

I read to Jude from a book about a man who had gone to sea and never returned. I guess his family must have thought him dead, but no, he became the world’s most famous castaway on an unnamed island off the Cannibal Coast of Guyana just a titch north of the Atlantic equator. Robinson Crusoe we discovered had a divine life or that’s what Daniel DeFoe wanted us to think. Damned and sunk, he was the only one to survive a terrible storm on the doorstep of an island lush with every commodity including goats and grapes. The providence redemption line runs heavily through this religious writer’s novel, but his narrative and thoughts are a treat to read, and discuss, especially for two castaways like us flung to a lonely part of Earth.

Well! That set the pattern for the next four days. Down and up went our barometer as four gales, one after another came and went, rocking us and wetting us before leaving behind a tranquil scene that lasted til the next band of dark clouds shut us in.

Fortunately Banyandah is our home with plenty to occupy our time below decks. Back aft I edited video, beginning the long process of putting together a story from the 50 clips and hundreds of photos we’d taken when discovering the lost Gould’s Post Track to Hamilton.

Up forward Jude did lots of things that she will mention – “Good weather, bad weather, being confined on board never bores me. Just watching the weather takes time, particularly when it’s bad. We had vicious winds and one horizontal hail storm so thick the dark waters and land were obliterated. In clear periods with the rain gone and the mountain peaks clear, I learned the names of every nearby mountain range: Erkine, De Witt, Propsting, and South West Cape, and picked out the peaks from the walkers maps we have on board, sketching some in both the ship’s log and my sketch book. I caught up reading historic notes, entered anchorage details, edited Jack’s draft blog, sorted photographs, cooked, made bread, and caught and cleaned flathead fish, not once but twice for a nice change from yellow-fin tuna. And still didn’t get half done what I would have liked. Tasmania’s dry summer had turned the button grass plains dry then brown, and the rains we had during the five days we were in Bond Bay was turning the scene green again. Always plenty to see, plenty to do.”

Somewhere towards the end of this vicious weather cycle the Green Machine was put together, so that after our fifth night, when the weather eased to overcast with no wind, we launched it for a paddle to look for Carver’s Boatyard. Jude had plotted a GPS position from a photo-map in Gary Kerr’s splendid book, “The Huon Pine Story.” It was entered into the handheld Garmin GPS before we paddled out of Bond Bay to cross a quiet sea towards the Davey River. Onboard we carried rain gear, a picnic, and our metal detector brought along with high hopes of unearthing bits of lost metal to help work out the layout of the boatyard.

Somewhere towards the end of this vicious weather cycle the Green Machine was put together, so that after our fifth night, when the weather eased to overcast with no wind, we launched it for a paddle to look for Carver’s Boatyard. Jude had plotted a GPS position from a photo-map in Gary Kerr’s splendid book, “The Huon Pine Story.” It was entered into the handheld Garmin GPS before we paddled out of Bond Bay to cross a quiet sea towards the Davey River. Onboard we carried rain gear, a picnic, and our metal detector brought along with high hopes of unearthing bits of lost metal to help work out the layout of the boatyard.

Working our torsos after so much time closeted up felt so liberating, we didn’t mind the chill of water off the paddles. Nevertheless, care was needed when big swells from the south broke on isolated rock patches near Curtis Point. Once around them we paddled close to the rocky shore that then dipped in and out of several tiny bays, none suitable for a shipyard, for they were either encumbered with rock or rose sharply from the water. In fact we passed Jude’s waypoint without sighting a location remotely possible to build 40 tonne vessels.

Shortly after 1815, Dr Thomas William Birch was granted a year’s concession to cut Huon Pine at Port Davey, and in the 1830s stands of Pines were found at the headwaters of the Spring and Davey Rivers. Upwards of forty piners and their families lived in a village at Settlement Point at the mouth of the Davey River where remnants of old pine pens, sawpits and chimney mounds still exist. On the opposite side of the river was a second settlement known as Piners Point.

Along this part of Payne Bay, Captain James Carver constructed a boatyard that had timber rails and cradles, as well as a forge, sawpits and accommodation for his workers. They built ocean going vessels to catch fish and whales, to take logs to Hobart and to shift cargo around as everything went by sea in those days. Carver’s Boatyard outlasted the timber-getters, who in 1882 had their licences suspended when the government feared the resource was being depleted, while Carver could still take the timber to build vessels, illustrating how much the colony needed ships.

About half a kilometre further north from where Garry Kerr shows the shipyard, we paddled across a small bay backed by forest that appeared flat on both sides of a small stream bisecting a sandy beach, and nodding agreement entered it sounding depths with a paddle as we neared the shore. Unencumbered by stone, the bottom shelved gently.

Once on land, a quick sortie to peek into the woods got us quickly changing into boots and bush clobber because it looked a perfect place for a boatyard. Down the middle of a flat area some 100 metres wide ran the trickling creek which seemed to come out a shallow valley. The trees were immense and thickly surrounded by lush understorey littered with the fallen, but straight away I discovered the remains of a sawpit. In olden times planks were sawn from huge logs using a two hand crosscut saw, one man standing on the log and the other in a pit under it. Of course over the 150 years since they were last used they’ve filled in with fallen vegetation, but nevertheless there still remains a tell-tale unnatural dip creasing otherwise flat land. We’ve seen them before. There’s another at Settlement Point.

Davey River Settlement from JACKandJUDE

Jude got busy along the foreshore with her metal detector while I bush bashed to find areas that might have held the accommodation or the forge and work areas. We have often turned up bits of corrugated roofing iron and other heavier metal bits buried under moss and foliage. But not this time. That didn’t stop us from visually mapping out the boatyard and in our mind’s eye imagining a Huon Pine vessel on the ways.

the last cargo of pines (salvaged) came out of Port Davey on the May Queen in 1931

The forest was wet, the air was also, so we gave this large area only a cursory once over, more intent on sucking in the character and atmosphere of the place than needing to do a full survey. We discovered three sawpits and poked around a tree where the detector indicated metal but that turned up only bits of charcoal and a rock which probably had set the detector buzzing. We weren’t sure, so we put everything back in place and continued our search along the shore. Here Miss Eagle Eye Jude spotted a pottery shard amongst the pebbles, maybe a piece of a cup or plate smashed when knocked off the cradle. That quickened the hunt and I was next to find another bit that had a different pattern. In all, within fifteen minutes we found four pieces of pottery, each with a different pattern. And that made us feel sure we’d walked the area of Carver’s Boatyard, last used circa 1886.

With our first objective ‘in the can’ we straight away shifted the Banyandah into Bathurst Harbour on a wonderland voyage that went past mountains abruptly rising from mirror smooth dark waters reflecting the peaks splashed with white quartz cutting a solid blue sky. We were mesmerised even though we’d beheld that spectacle many times before. But making the experience even greater, not one manmade object interrupted this parade of breathtaking views.

Surprising us, as the arm enclosing Wombat Cove slid past to expose the craggy mass of Mount Misery, we found this popular anchoring spot empty, begging for company. So in no time at all we had shifted our floating home to a totally new world. One dominated by white cliffs running along dark waters, where the cliffs became smooth green brown slopes inviting us to climb up to the fierce rock monolith that promised panoramic views of an area unchanged since creation.

A cold fresh wind off the Southern Ocean had sent all cloud scampering and now invisible bullets began to attack, rushing through the valleys either side of a blocking hill. Sometimes they collided behind us at the head of the tiny bay. Other times they pounced in front of us, creating darkening ruffles that would visibly race across the bay and then be gone as if they’d never been. Fortunately by a miracle of geography these ‘Whirling Dervishes’ didn’t come near us.

Rugged up in bush pants, sweaters, windcheaters and knitted beanies, Jude and I rowed to the low corner where we knew the beginning of a path leads through the shore bush and up onto the open mountainside. Cold, clear and bright, everywhere seemed extra real in well saturated glimpses that changed every few paces hiked higher, giving us a good reason to pause and catch our breath bewitched by a new vista. Without a destination and really only wanting to fill our souls with Earth’s beauty, we climbed higher and higher while our eyes examined everything. First thing that caught our attention, it was so dry that some of the crustacean burrows had collapsed. Normally they would stand several centimetres tall, but many mud tubes had disintegrated into mounds of fine sand. The other very apparent change, over large areas the scant vegetation and small leaf ground cover, instead of green, was burnt orange. Seems the recent rainy days had not yet returned life to this strange land. Our fascination with the granite rocks coated in yellow, orange, and green lichen was also renewed. But above these interesting things, we just sucked in the freedom of open space across a wild world made even wilder by the icy blasts.

We have in the past, spent many weeks exploring the numerous nooks hidden away in the mountainous folds of Bathurst Harbour, finding that this timeless land sends worries and cares away. But this time, for us the clock was ticking. We’d spent the better part of the summer in the bush finding a track that had been cut by the early explorers, and for the remainder of the fine weather ahead, we wanted some prime time at the other end of Tasmania in the Furneaux Island Group which guards the eastern entrance to Bass Strait.

Having lost five days through stormy weather, we felt pressed to get on with our second objective. That’s the subject of our next blog coming out shortly.

Having lost five days through stormy weather, we felt pressed to get on with our second objective. That’s the subject of our next blog coming out shortly.

Chapter 4 – Eden Lost Needwonnee

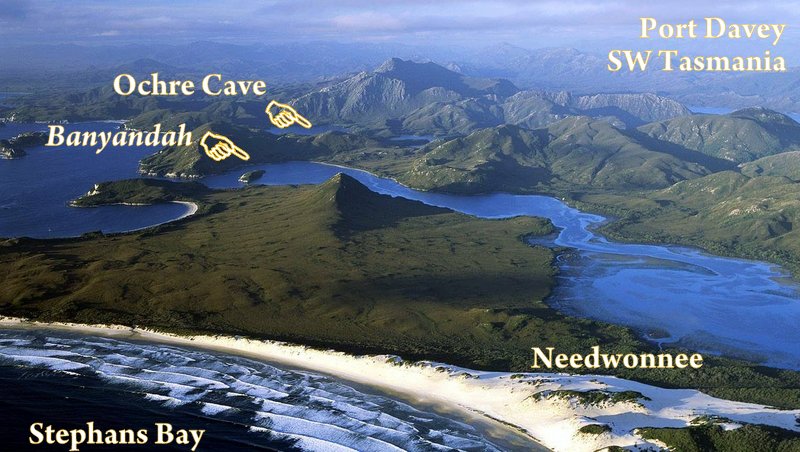

During our first visit to Port Davey in 2009 we had parked our lady in an outside bay and had walked across a short neck to Stephan’s Bay, which is exposed to the full might of the Southern Ocean. Not only did the impressively shaped rocks and islands lying just offshore excite us with their prehistoric majesty, so did the long semicircle of wide yellow sand edged with row upon row of foaming white breakers. Untouched except by nature, amongst massive clumps of golden brown bull kelp ripped from the ocean floor by forces we could only imagine, we’d found a few large sea creatures dead on the smooth beach. Even though those images had a powerful impact, it was the sand mountains filled with a myriad of shells that impressed us the most. Some were rather large such as abalone and amongst the many others were whorls, augers, and green shells. There were also the bleached bones of sea creatures and large birds. All of these seemed to erupt in layers out of the massive sand hills bordering the south end of Stephan’s Bay.

During our first visit to Port Davey in 2009 we had parked our lady in an outside bay and had walked across a short neck to Stephan’s Bay, which is exposed to the full might of the Southern Ocean. Not only did the impressively shaped rocks and islands lying just offshore excite us with their prehistoric majesty, so did the long semicircle of wide yellow sand edged with row upon row of foaming white breakers. Untouched except by nature, amongst massive clumps of golden brown bull kelp ripped from the ocean floor by forces we could only imagine, we’d found a few large sea creatures dead on the smooth beach. Even though those images had a powerful impact, it was the sand mountains filled with a myriad of shells that impressed us the most. Some were rather large such as abalone and amongst the many others were whorls, augers, and green shells. There were also the bleached bones of sea creatures and large birds. All of these seemed to erupt in layers out of the massive sand hills bordering the south end of Stephan’s Bay.

Amazed and floundering to comprehend, we had explored those sand hills, marvelling at the massive midden under our feet. And when we reached the ridgeline that overlooks the beautiful blue ocean fringed in white, across a long sand blow we had spied Hannant Inlet, a long slender dark body of water hemmed in by a range of mountains to its east and cut off from the sea by a narrow band of coastal vegetation. Stunned by its beauty we realised that this was the homeland of the Needwonnee Clan.

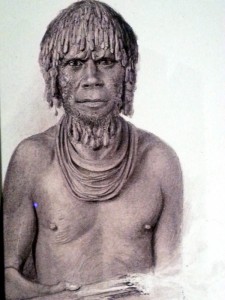

You’ve probably never heard of these people, but here in Tasmania before white man invaded this island the indigenous Aborigines lived in harmony with Earth for more than thirty thousand years. That’s an amazing achievement considering that Christ walked the earth only two thousand years ago. Tasmania’s northern reaches with its milder climate and better terrain held the greatest numbers of Aborigines. Smaller in numbers, the clans that occupied the southwest corner were the Toogee people, made up of four clans. In this part of Port Davey, occupying the land from the Iron Bound Ranges about 45 kilometres to the East and along Port Davey’s southern shores to the west coast, were the Needwonnee Clan numbering probably no more than several families. North of them were their cousins, the Ninene clan who roamed Bathurst Harbour’s northern shores and Kelly Inlet to seaward. Further north from Low Rocky Point were their distant relatives the Lowreenne Clan who hunted northwards to Macquarie Harbour. And roaming the massive waters around that harbour were the Mimegin people. Little is known about these people except that they did not war with their neighbours and took only what Earth could sustain, sharing a simple love for Earth believing all life came and returned to the creator of life. Their record run of harmony disastrously ended when white man invaded their island.

You’ve probably never heard of these people, but here in Tasmania before white man invaded this island the indigenous Aborigines lived in harmony with Earth for more than thirty thousand years. That’s an amazing achievement considering that Christ walked the earth only two thousand years ago. Tasmania’s northern reaches with its milder climate and better terrain held the greatest numbers of Aborigines. Smaller in numbers, the clans that occupied the southwest corner were the Toogee people, made up of four clans. In this part of Port Davey, occupying the land from the Iron Bound Ranges about 45 kilometres to the East and along Port Davey’s southern shores to the west coast, were the Needwonnee Clan numbering probably no more than several families. North of them were their cousins, the Ninene clan who roamed Bathurst Harbour’s northern shores and Kelly Inlet to seaward. Further north from Low Rocky Point were their distant relatives the Lowreenne Clan who hunted northwards to Macquarie Harbour. And roaming the massive waters around that harbour were the Mimegin people. Little is known about these people except that they did not war with their neighbours and took only what Earth could sustain, sharing a simple love for Earth believing all life came and returned to the creator of life. Their record run of harmony disastrously ended when white man invaded their island.

Ever since the day we’d stood atop that sand ridge above the massive Needwonnee midden, we dreamed of returning one day to paddle down the shallow Hannant Inlet to the shore opposite the sand blow and midden, so that we could explore and walk the ground of a clan that had lived in harmony with Earth for what must be the longest time of all Earth’s people.

As we’ve aged and our family has increased, our desire to bring the marvels of Earth to those unable to witness them in person has sharpened. And in that time we have seen more people becoming disconnected to Earth and this has increased our fear that this marvellous creation is under a growing threat. The Needwonnee, primitive and isolated though they might have been, somehow for an extraordinarily long time lived in peace and harmony with Earth and her creatures. We can only guess at the depth of their knowledge of the other creatures inhabiting their area. Maybe they could communicate in some way, but for sure they would have felt intimately the manner and movements of the creatures, and while we may not desire to be so restricted, the Needwonnee represents something that is quickly being lost – a connection to Earth that brings admiration, love, and respect.

Jude and I are storytellers who use words and images to convey ideas and we realised that here was an opportunity to record this unique country on widescreen video with dialog illuminating the facts surrounding what are one of the most amazing people to have inhabited Earth.

Across from Wombat Cove in Schooner Cove there’s a cave where for millenniums the Needwonnee families gathered to frolic and swim, eat mussels and collect ochre for ceremonies. It lies within full view of the majestic Mount Rugby, the area’s largest peak, and just over the ridge behind it runs the long shallow Hannant Inlet.

On a sparkling sharp windless day we set up our cameras in front of this cave where Jude introduced these early inhabitants and then we moved inside to film the thick layers of mussel shells laid down since the dawn of mankind. The seam of ochre dug by countless spiritual leaders is shown still exposed orange and red.

After that great day we shifted Banyandah out of Bathurst Harbour, and leaving behind the protection of Breaksea Island we went into the narrow entrance to Hannant Inlet. Garry Kerr had taken us into it when we were taking the Jane Kerr back to Strahan, but fearing grounding in the shallow depths he went in only a short distance. With Banyandah’s engine just ticking over we ventured slowly in towards the northeast, me on the dodger top watching how the small swell peaked on obvious shallows closer to the western shore. That end is blocked by the long and slender Lourah Island. Turning the other way, to the east we eased our lady between the shore and Lourah Island with barely half a metre under us, slowly zigzagging, searching for greater depth, which we found close to the island. Just before the end of the island, a very nice pond of about three metres in depth opened up, where of course we set the Boss, giving him a big pull to test his grip.

Straightaway, while we still had good light, I rowed about with a sounding line and discovered that we had parked plumb in the centre of a largish area clear of rocks that quickly shallowed to waist depth water just past the island’s rocky point. In calm conditions, surrounded by glorious views, we then celebrated our wonderful day’s achievement while busily preparing for an even bigger one the next day.

Early the next morning, after filling the Green Machine with cameras and sound gear, our bush clobber, food, first aid and safety gear we set off, blissfully filming everything as it happened. We absolutely love doing this, using our gear and skills on missions that in the very least will transport our family and friends to very special places. That early morning paddle revealed many shallow patches lying on the other side of the island, confirming that a keel boat could get no further in than ours.

Early the next morning, after filling the Green Machine with cameras and sound gear, our bush clobber, food, first aid and safety gear we set off, blissfully filming everything as it happened. We absolutely love doing this, using our gear and skills on missions that in the very least will transport our family and friends to very special places. That early morning paddle revealed many shallow patches lying on the other side of the island, confirming that a keel boat could get no further in than ours.

Perhaps a kilometre wide, the inlet runs for about three or four kilometres to a narrow neck that then opens into another equally sized body of water. On our right as we headed south, Sunset Hill rose in a conical mound clad with low growth. Past it, where the water narrowed were rocks coming from both shores and for the first time we wondered whether our mission would come to a full stop right there. Ahead were large flocks of black swans that we know inhabit shallow depths so they can feed upon the grasses growing on the bottom. Indeed, immediately upon passing that narrow neck we found ourselves in a channel bounded by water too shallow even for a kayak. But by watching for the very smooth water indicating shallows, we weaved a way through the banks until our GPS pointed to a small indentation that we had plotted off the chart.

Grounding a good hundred metres out from the trees gave us our first hint of the difficulties awaiting us. Stepping out, I immediately lost my Croc deep into soft muddy sand and only by putting part of my weight back onto the kayak was I able to pull us closer in until Jude too had to join me in the sticky goo.

“We should have brought an anchor,” she said while I was urging her to pull harder to get the kayak close enough to reach the nearest tree with the painter now joined to the long length of sounding line.

Our first impression after securing our craft were gasps of astonishment at seeing the placid beauty of all those black swans against the stark mountains reflected perfectly on the glassy water. Along the shore ran a verge of what’s called swan-grass, deep verdant green flats of dense short grass that the swans rest upon, broken by an odd tea-tree to nip around, backed by a glorious Banksia forest with taller eucalypts interspersed throughout.

From records kept up to 1835, a total of only forty seven Aborigines were captured on the west and southwest coasts. Therefore the Needwonnee clan probably was not more than one extended family. A number of brothers and a few uncles perhaps, with wives and children roaming a harsh wild land seeking sustenance as they could. For shelter, family groups built dome shaped huts framed with long intersecting branches thatched with long grasses. Their huts were warm, comfortable and quite weather proof. They were often clustered together near fresh water. In their wild state they were a contented people. Skirmishes with neighbouring tribes were very rare and it was not until they found themselves engaged in the bloody and hopeless contest with the White, that they became morose, sulky, sullenly and wretched.

Changing into bush gear and boots, we took up our day packs, and with a tripod under my arm and Jude clutching her camera, we entered the forest excited and hoping to immediately find a grass thatched round hovel. Ha! Such optimism after a lapse of several hundred years. But that didn’t stop our imaginations conjuring up smoky fires next to the fresh water creek exiting that indentation.

Changing into bush gear and boots, we took up our day packs, and with a tripod under my arm and Jude clutching her camera, we entered the forest excited and hoping to immediately find a grass thatched round hovel. Ha! Such optimism after a lapse of several hundred years. But that didn’t stop our imaginations conjuring up smoky fires next to the fresh water creek exiting that indentation.

Not surprisingly the area was quite flat and to get my bearings I climbed a tree just vacated by two curious orange bellied parrots, and then lead my adventurous lady off towards what I thought was the sand blow leading to Stephen’s Bay.

Jude will follow me to the ends of the earth, hardly ever complaining when I stuff up and go the wrong way, which I did that morning. I kept avoiding the myriad of small waterways where the ground was soft and ended up in low tea-tree that got thicker and more difficult when the banksias crowded us with their sharp branches. Pushing through we then ran into patches of vine and succulents taller than our height that we’d never seen before. Lots of time we’d be sidetracked, turned around, and would stop awhile to examine things more closely. It can’t be helped. Instead of an uneasy feeling of being lost, it’s more akin to Alice in Wonderland where new discoveries appeared round the next bush. We often follow animal trails, small as they are, looking for their scat as indicators just as indigenous people around the world still do.

Jude will follow me to the ends of the earth, hardly ever complaining when I stuff up and go the wrong way, which I did that morning. I kept avoiding the myriad of small waterways where the ground was soft and ended up in low tea-tree that got thicker and more difficult when the banksias crowded us with their sharp branches. Pushing through we then ran into patches of vine and succulents taller than our height that we’d never seen before. Lots of time we’d be sidetracked, turned around, and would stop awhile to examine things more closely. It can’t be helped. Instead of an uneasy feeling of being lost, it’s more akin to Alice in Wonderland where new discoveries appeared round the next bush. We often follow animal trails, small as they are, looking for their scat as indicators just as indigenous people around the world still do.

It’s a bit like sailing an ocean using an old fashioned sextant. While it may be harder and not as accurate as using the modern devices, the reward is it keeps one in tune with Earth and the heavens. Pushing through native wilderness we see first hand how the other creatures cope. We see lots of different vegetation, critters and insects, what grows best, and how things like land slides and sand blows change the environment. It’s this first hand contact with Earth that we’re promoting, and from our experience with our own grandchildren, we know how excited young people get when they have those experiences.

We travelled through the bush for several hours, discovering later that we’d stayed within the low lands contained by two sand dunes that we never found till the very end. What we did find though is that this area contains many passages of two water sources. One flows towards Hannant Inlet, the other towards the sea. They are the givers of life for that area. Lots of square scat indicated the abundance of wombats, and flattened grasses, sleeping area for wallabies and pademelons. The succulents in the wetter areas had tuberous roots. The place was an Eden bordered by an ocean filled with seafood and an inlet alive with fowl. We even walked upon tracks made by larger creatures, possibly an ancient path of the Needwonnee people. The earth changes, it’s alive, so we couldn’t say for sure. But what we can say is that for several hours we were part of an ancient tribe surrounded by Mother Earth, hearing surf and feeling the sun’s warmth.

We came out the bush where it thinned and spied a dune just like in the Sahara and through the branches saw a wallaby not far away. As we were hidden, it wasn’t aware straightaway, and if I had been a true clansman with a sharp wooded spear we’d be having wallaby roasting on our cooking fire that night.

We came out the bush where it thinned and spied a dune just like in the Sahara and through the branches saw a wallaby not far away. As we were hidden, it wasn’t aware straightaway, and if I had been a true clansman with a sharp wooded spear we’d be having wallaby roasting on our cooking fire that night.

Instead I crashed out the bush, sending the critter jumping several metres away where it turned unafraid and curious.

Hunting was men’s work while collecting plants and diving for seafood was the task of women. Coastal Tribes like the Needwonnee in this area were living primarily on shellfish, mostly mussels, and other sea foods such as crabs, sharks, and rays. Another favourite food was the opossum which was hunted by women. They climbed trees to kill the animals with a club or stone axe. To ease climbing large trees, step-like notches were cut into the stem, and it was precisely such steps that were the very first indication of a human presence noted in 1642, by Abel Tasman. This was 130 years before the first Tasmanian person was actually seen, by Nicholas du Fresne in 1772.

Tasmanian prehistory has many unexplained oddities. One of the most startling of these was first discovered when Tasmanians watched early Europeans catch and eat scale fish. The aborigines were clearly shocked and displayed unmistakable signs of horror, rather as most of us would react if we saw someone eating worms.

Meat was roasted over an open fire while other foods such as eggs were also roasted. Making fire can be a difficult business even for people with a lot of practice, especially if it has to be done at night or in the rain. It’s not sure whether they created fire by either of the two methods used by early folk – rubbing two dry sticks together or striking fire stones against each to ignite dry kindling – Or did they have to wait for lightning strikes? What we know is they kept it going using firesticks. These were pieces of soft wood or twisted strands of fibre and bark with dry moss which were carried around smouldering.

By the time we broke free of the forest, most of the morning cloud had been burned away by a hot sun, revealing a cerulean sky in every direction. It saturated the landscape with the colours of earth as we climbed out the forest onto the toe of a massive dune dotted with tracks of small critters, the only blemishes to its surface. We hardly could bring ourselves to mar such perfection and just stood aghast, filming and taking pictures, marvelling at such simple beauty. Like Lawrence of Arabia we finally trod off towards the incessant sound of breaking surf that got louder til we breached the edge and saw blue ocean extending to infinity.

The air was dead still and yet the sea rolled in past the towering tooth-like Wedge and East Pyramids Islands, where seals basked in sunshine. The seas still broke in wave after wave upon the semicircle of sand, just as we remembered from our first visit six years earlier, and as it has since the Needwonnee first walked this land 30,000 years ago.

Atop that sand ridge exposed to nature in every direction, the spirit of Earth entered me and I felt a part of a much larger creation, one so far beyond my conception that I took solace that all would be right, and I bowed by head and gave thanks. Beginning at my feet down to the shore, the sand looked dimpled, bumpy, and uneven. Some bits sparkled, others glinted rays from the sun. Upon looking closer this nutty nugget was all shells and bones of sea creatures erupting from the sand. It stretched both to our right and left a hundred metres in height – proof of a people living here for a countless time.

While Jude got busy taking stills, I set up my tripod to gather background and close up video. Then, next to three prominent mounds filled with the remains of Needwonnee feasts we got together to film the story.

Behind us, white surf burst upon that apron of sand while Jude paced back and forth reciting her lines. After I rigged up her lapel mic, we worked through her entry and her marks then we recorded our first take. It took several before we were happy and could set off to explore further. What a wonderful day. Just the two of us at the ends of Earth, observing and learning. If we had been hot blooded kids we’d have frolicked naked in the surf, instead, we sat in some shade, held hands and cuddled.

Late in the afternoon we knew we’d not return through the bush and with great reluctance, stopping and turning for many a last look, we trod off across the top of the sand blow hoping it would lead back to our indentation on Hannant Inlet. Upon unmarked sand we walked above the scrub that linked the two waters till we came to an abrupt end where the sand fell, spilling over time straight into forest. I liked walking on the sand and did not want to enter the dark unknown again, but there was no choice. Jude went first, sliding down the sand face, dodging pointy branches till I saw her step onto mossy ground that oozed black tea coloured water up around her boots as she sank. I filmed her descent then quickly followed into a world of puddles. Stepping tree root to tree root, we reached a mound and spied our indentation a few hundred metres farther on, and then descended into a green fairyland of swan grass growing along a waterway obstructed by trees. It was so easy. Our only obstacle came when we found ourselves on the wrong side of a steep sided creek and either had to take our boots off to chance a crossing or find another way back to our kayak.

As the tide had fallen, the muddy foreshore was doubly wide so I took a deep breath then lead us on a long march across the inlet, praying we’d not sink. Providence provided firm footing to a dry rock outcrop where we picked up millions of small gnats that kept us company the rest of our journey back to Banyandah.

What a welcome sight to see the Green Machine. Would have hated to bush bash all the way home. But my! Our kayak was miles from the water.

It wasn’t fun or easy dragging our craft over the gooey mud, extricating our feet after every heave forward. We barely managed that. Then we transported all our gear from shore to it before Jude washed her feet and got in. I then heaved the kayak a bit further out to get her afloat. Relieved to the max, all we wanted was to get home and started paddling with less than a fingers depth under us. Grounding several times, it would have been tedious if the flocks of swans and wonderful mountains hadn’t been so breathtaking. Of course we got home just fine and had a glorious moment rejoicing that we’d fulfilled a long held dream.

Those days of glorious weather were the harbinger of a massive frontal system. More rain was coming. Days of it in fact, and since we didn’t want to sit around through that again, we elected to depart before dawn next day on a passage under the island to Tasmania’s east coast. The weatherman predicted that we’d be blessed with prefrontal northwest winds for the sixty-five mile journey. But I had my doubts. We’ve tried several times to use the hot winds before a front only to find them wanting.

At four the next morning I put a cuppa beside my sleeping beauty and nudged her awake. We’d already prepared our ship for the voyage around the three capes exposed to the Great Southern Ocean. So again in darkness all proceeded to plan. Raising the mainsail as we left the narrow gap from Hannant, it found a very pleasant light northerly breeze. With the hint of dawn backlighting stark treeless mountains and Banyandah under sail we dodged off lying islands heading for open sea. It doesn’t get much better than that.

From Davey, it’s about nine miles before you can turn east around South West Cape and we did these under sail as the sun rose over the ranges, and for a third time since leaving Strahan we landed another yellow fin tuna! Everything was grand until the day became warmer and the rising heat took away our beautiful wind, and we had to spoil the silent majesty by starting our noisy engine. Oh well! Such is life. The sea then became glassy and we debated whether to stop at Maatsuyker Island or maybe pull into New Harbour and wait for wind. But the forecast disturbed us. Gales were forecast for that night. So instead we entertained ourselves by passing as close to each island as we dared, going through passages we’d never attempt even in moderate weather. Caverns appeared at water level and we saw a hole chinking sunlight right through one. Seals were sighted basking in the sun, flippers raised as if to say – Hey! Don’t run us down. And cute fairy-penguins were about too.

The forecast northerly winds never returned so we kept motoring. It was good that we did. Reaching Recherche Bay around six pm, the sky turned black. Snugged up to the shore, the Boss deep in good holding bottom well protected from the west, it blew wildly overhead that night but we slept peacefully unawares, bar the light pitter-patter of rain.

Stopping to wait for wind at Maatsuyker or New Harbour could have proved disastrous as seventy knot gusts were recorded there overnight. Happily the Great Escape ended with a great success.

Adding further value to our single DVDs –

Hi Jack&Jude – thanks once again for bringing life aboard to those of us currently stuck on land. A great insight into the lives of the Needwonnee clan and of the passage around South West Cape. Am just reading Batavia by Peter Fitzsimons – good read. Having spent time in the Abrolhos Islands, you mightt find it interesting.

Best regards – Bruce&Anne Stewart

Jack & Jude, the writing just gets better and better. I’ve followed you guys since I bought your first book way back when you did a presentation one evening at the SA Yacht Squadron. You bring profound inspiration to myself and hopefully any sailor, want to be sailor or just plain sensible folk who happens upon you blog. No need to encourage you to keep going, because I know your enthusiasm for living the life you do is unbound.

Thanks for being who you are and sharing it with the world.

Onward !! Mal

Terrific Mal, delighted you’re enjoying our blog. That was a fabulous night at the Royal, really enjoyed the company and interest. Lets do it again and we’ll show our Coral Sea film. Team Tujays

Hi Jack and Jude.I just thought I would thank you for the inspiration and enjoyment your writing and films give to me. The cruising guides, books and blogs are a wonderful source of information and are in a down to earth and easy to devour style. The amount that you GIVE to other people is something to be emulated by us all, but for most I just wanted to say thank-you for what you give to me. Cheers Brian Dorling.

Thanks very much, love comments like yours, they encourage us to keep at it. As you can imagine it takes a bit of effort. So many really nice folk have given us a hand, encouraged us, and now that we’re in a position to help, we really enjoy giving a hand. Cheers J & J

Hi Jack and Jude. I was thinking only yesterday of Cremorne and the building of Banyandah in your back yard.I love reading your blogs but am not good with computers so I have not tried this before. I am now sharing a house with Fleur at Terrey Hills -as big an adventure as I get these days, but the bush walks are lovely here. love, Di.

Jude here sending you big hugs Di. Remember kids in tow off to tennis, such good times. have your new number and will give a call. XOXOXO

J & J, thanks for sharing. That coast looks so colourful, though the do is held facing west made me shudder; an inhospitable Lee shore on its day.

I sense a hunger for the wealth of cultural knowledge that we all lost along with the destruction of Aboriginal tribal ways.

Thanks, Terry

Colourful and unique, a very special part of Earth. And a lee shore for sure, but with modern weather technology and care, it can be explored. Plenty of cray fishermen work this west coast.