Dreams, Daring, and Death ~ May 14

Our summer has flown and storms are now striking the far South West nearly one a week, their screech and cold fury focusing our thoughts on planning an escape. This summer we’ve accomplished so much, in both Macquarie Harbour and Port Davey, but it’s time to skedaddle round Tasmania’s sometimes-vicious south coast, a voyage often dreaded. Intimidating many say.Jude and I first made this journey in 2009, motoring pretty much every mile on a limp flat sea that let us poke into several south coast bays, admittedly while casting many a long look over our shoulders.

Our summer has flown and storms are now striking the far South West nearly one a week, their screech and cold fury focusing our thoughts on planning an escape. This summer we’ve accomplished so much, in both Macquarie Harbour and Port Davey, but it’s time to skedaddle round Tasmania’s sometimes-vicious south coast, a voyage often dreaded. Intimidating many say.Jude and I first made this journey in 2009, motoring pretty much every mile on a limp flat sea that let us poke into several south coast bays, admittedly while casting many a long look over our shoulders.

Some wait for a storm to pass then motor at speed across windless, big swells. Not us this time. We wanted to sail the seventy-odd miles around the stegosaurus spine of South West Cape where big swells roll in from the Great Southern Ocean, then past the lonely wind blasted isles of Maatsuyker and the solid bulk of Cox Bluff, and on along the rugged coastline to the dramatic perpendicular cliffs of South Cape to finally pass the jagged South East Cape into the safety of Recherche Bay.

But before leaving we had one last goal to achieve – locate the enigma of Bathurst Harbour, the gravesite of Critchley Parker. In March of ’42, a young man arrived filled with passion and ideals, hoping to find a suitable location for a refugee settlement for Jews under persecution from the Nazis. He envisaged a Jewish homeland encompassing the whole of the South West with a city named Poyunduc, the Aboriginal name for Port Davey that would manufacture all manner of products using hydroelectric power.

Ill equipped for his solo trek in the South West’s harsh terrain and changeable weather, gambling all, he lost his life in horrible lonely conditions, his body undiscovered for months even though a large manhunt had been mounted. Not till half a year later when Clyde’s dog hunting ‘roos’ found his decomposing body in a tattered sleeping bag, the tent in shreds. Janet Fenton states in her book about her aunt and uncle, “Clyde was so affected by the sight that he had a horror of sleeping bags for the rest of his live.” Buried where he died, a simple cross marked the spot for five years until Critchley’s mother arranged for a gravestone to be erected by Hobart stonemason Leo Luckman. Its position is marked in some guides, but you’d be lucky to find it without a GPS position, kindly given to us by Andrew off Reflections from Hobart.

After our exploration of the Old River, we passed the night tied to trees, where next morning high above our mast echoed melodious singing that woke us to bright sun and a completely calm Good Friday. With decks so wet as if it had rained, a sign the weather would turn stormy, we quickly retrieved our lines and made a beeline over the river bar without mishap.

Anchored in Parker Bay two hours later, before going ashore we searched the lower slopes of Mt. Mackenzie for signs of Critchley’s grave, wanting the closest landing place. But all we saw were obstacles of small creeks, melaleuca, tea-tree, and buttongrass.

Jude and I clamoured onto shore next to a small stream convinced we’d find his grave just up that slope, and started following the GPS to the position less than a hundred meters away. But after gaining the knoll we had to descend into thick stuff up to our shoulders, cross the stream, then force our way through dense melaleuca, skirting razor grass in the deep gulley, ever watchful for Tasmania’s deadly snakes. When mere metres away, we still couldn’t see it, until a final push through more head height clumps suddenly revealed the large headstone crafted from grey quartzite collected from Balmoral Hill across Bathurst Channel. So far from family and friends, Critchley might as well have been laid to rest on the moon.

Jude and I clamoured onto shore next to a small stream convinced we’d find his grave just up that slope, and started following the GPS to the position less than a hundred meters away. But after gaining the knoll we had to descend into thick stuff up to our shoulders, cross the stream, then force our way through dense melaleuca, skirting razor grass in the deep gulley, ever watchful for Tasmania’s deadly snakes. When mere metres away, we still couldn’t see it, until a final push through more head height clumps suddenly revealed the large headstone crafted from grey quartzite collected from Balmoral Hill across Bathurst Channel. So far from family and friends, Critchley might as well have been laid to rest on the moon.

Late afternoon saw the barometer falling fast, so we shifted into Frogs Hollow and weathered a gale that heaped heavy hail around our scuppers. Waiting another few days for the south-west swell to abate, Banyandah was shifted to Schooner Cove and made ready for departure. That night upon calm water I slept poorly, worried the forecast wind would arrive too early and make our westward passage across the exposed Port Davey difficult, maybe dangerous in predawn darkness.

After hearing midnight’s eight bells I’m sure I heard every bell until four the following morning and rose ready for action into blurry moonshine between thin clouds. The scant light helped us see the black cliffs as we motored through the passage to Breaksea Island, clearly outlined by glittering white breakers. Immediately I felt both foolish and chuffed, the light wind was in our favour. But not having seen either sea or swell for more than a month, we at first found it disconcerting until old routines kicked in.

Before the advent of satellite navigation, Jude would have been at the helm with me on the foredeck, probably freezing cold, searching the abyss for any hint of breaking water or black silhouettes of small islands. But this morning, outside of watching the repetitive two blinks on Whalers Point, Jude steered while every few minutes I popped up from the nav station for a prudent look round. Motor sailing at speed, our course cleared Nares Rocks then to seaward of Big Caroline Island and Hilliard Head, both still vague dark shapes.

The eastern skies started getting lighter as the breeze increased so we shut our Perkins down. Must say, slipping silently up and over swells of less than two metres while the giant teeth of East Pyramids could just be seen in soft early light simply thrilled us. Half an hour later, red and golden rays of dawn, like a meteorite striking, shot rays over the South West Cape Range behind Window Pane Bay.

Abeam SW Cape in increasing wind, we were scampering along at sixes and sevens, and I put out the trolling lure. Five minutes later our digestive juices got a kick-start as I hauled in a yellow-fin tuna nearly half my length. Muscling him over the railing took both our strengths but thankfully my knife quickly ended his struggle. Having not caught a big pelagic fish for quite some time we were ready to celebrate, but first, butchering the animal in those seas required a danseur’s balance. We wasted little. Besides lunch and the immediate two dinners, Jude had plans to preserve the remainder in bottles.

Abeam SW Cape in increasing wind, we were scampering along at sixes and sevens, and I put out the trolling lure. Five minutes later our digestive juices got a kick-start as I hauled in a yellow-fin tuna nearly half my length. Muscling him over the railing took both our strengths but thankfully my knife quickly ended his struggle. Having not caught a big pelagic fish for quite some time we were ready to celebrate, but first, butchering the animal in those seas required a danseur’s balance. We wasted little. Besides lunch and the immediate two dinners, Jude had plans to preserve the remainder in bottles.

To appreciate its full majesty, SW Cape must be witnessed. Photos simply don’t convey the raw Nature of this rocky spine boldly withstanding the Southern Ocean’s powerful onslaught. Adding greatly to our fascination, the fresh breeze gave lift to Giant Albatross and they soared past our wake, wingtips brushing wave tops. Also on display were Fairy Prions, the bluest of all with a bold black W across their wings and body. They hopped across the seas looking for tiny krill and other titbits. Now in their domain, the open sea no matter how huge provides them food; the wind, no matter how strong provides their means of travel.

An hour after rounding the Cape, wind from the west started bowling us along. Now recording eights and touching nines, we put three reefs in the mainsail as Maatsuyker Island approached. We had seen its wind-shorn green capped ridge from the north twice before, once at sea, once on land. This time we were keen to see its southern side and shot the gap between black Needle Rocks silhouetted against Maatsuyker lighthouse, and the straight sided Mewstone.

An hour after rounding the Cape, wind from the west started bowling us along. Now recording eights and touching nines, we put three reefs in the mainsail as Maatsuyker Island approached. We had seen its wind-shorn green capped ridge from the north twice before, once at sea, once on land. This time we were keen to see its southern side and shot the gap between black Needle Rocks silhouetted against Maatsuyker lighthouse, and the straight sided Mewstone.

Ever increasing, the wind got to gale force and not just once did we half-wish we’d just doused the mainsail. But at the start of a new blow, the sea remained fairly gentle, so we hung on sitting under the protection of our dodger, enjoying the magic of sailing the southern sea within sight of the south coast while racing the sundown into the safety of Recherche. Unchanged except by nature, it thrilled us as it had Matthew Flinders and D’Entrecasteaux before us. So imagine our horror when rounding the last barrier of SE Cape, we saw the effect man has had.

Well before anchoring at The Coal Bins, the grey-white skeletons of so many dead trees had us shaking our heads in disbelief. The devastating plant disease Phytophthora is arguably the greatest threat to biodiversity. Already widespread, with few management options available to control this spiralling disease, it is spread primarily by people. Crikey! Most often we mean well. But struth! We sure screw up sometimes.

Isn’t it time to seriously discuss our rapidly increasing numbers.

The Last Stand ~ May 7

In the early morning after a mild storm had passed, the sky brightened to clear lapis blue and the air stilled as if Aeolus the wind god was holding his breath. Nudging Jude from her first moments of waking, I whispered “C’mon. The day’s perfect to try crossing the Old River Bar.”

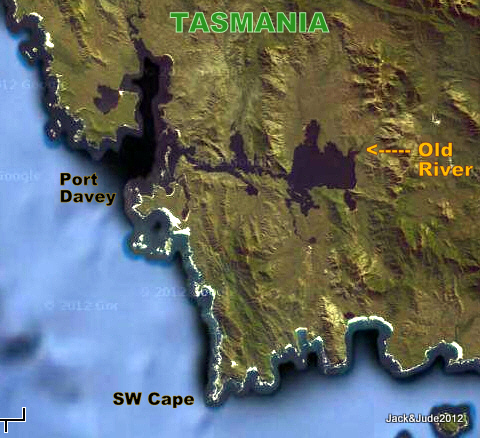

Across the mirror smooth basin surrounded by bare mountains of buttongrass and white rock, the river conquered by early Huon piners had been tantalising us since arriving in Bathurst Harbour. Draining tall mountains to its northeast and more from Ripple Mountain and Mt Picton where in the 1860s piners Doherty and Longley dragged their punts up rapids, risking life and limb to harvest timber that’s feather light and never rots.

The day before the storm, Andrew and Judy off Reflections out of Hobart had rafted alongside. While the ladies brewed coffee, Andrew, an engineer and Coast Radio volunteer with a keen interest in the remote South West Tasmania, took me below to dig out a sounding device he’d constructed that clips onto his rubber ducky and connects to an upmarket GPS which then records data from the sounder. Clever. All he has to do is traverse back and forth to sound a river mouth or bay and the device will log depths at exact locations.

“You beauty,” I’d exclaimed when he offered his soundings for the notoriously shallow Old River Bar exposed to the stormy southwest. Andrew explained he’d just confirmed this data the other day when taking Reflections, drawing five and a half feet, a mile upstream. Great! Now Jude and I could do just that very same thing, take our six-foot draught Banyandah into the safety of the river to launch the Green Machine for a paddle up river.

Andrew then further delighted me by handing across his coordinates of a stand of mature Huon pines found further up that river. Isn’t it grand how the yachting fraternity helps each other.

When we got underway Andrew’s waypoints were already programmed into our GPS, coloured blue for those with sufficient water and red for those too shallow. (Anchoring Guide updated)

To the slow throb of our six-cylinder diesel Banyandah edged closer to Swan Point, its abrupt rock ledge a mere boat length off when we turned to face a calm expanse of mirror bright water surrounded by rising land topped with green forests. Across the mile gap to a narrow opening we could just make out odd bits of timber poking up and wondered whether they were old channel markers or the limbs of dead trees stuck on shallow flats. With little time to ponder, a hundred metres on lay our first challenge, a patch of skinny water with just our draught if Andrew’s soundings were correct.

Bathurst Harbour is somewhat similar to Macquarie Harbour in that its rise and fall is not just determined by astronomical movements. The huge expanse of water is held back by a narrow opening not much wider than Hells Gate, and so both barometric pressure and wind direction also affect its depth.

I’m always on edge when doing these things, wondering whether we’ll clear, the rum coloured runoff from buttongrass and tea tree making it impossible to see down more than a few inches.

Watching Banyandah’s blinking icon jump forward after an excruciating long delay I called up, “Right a titch, another 5 degrees.” This is the most nerve-wracking way to navigate, waiting for that silly blinking icon to update from an unseen satellite while we blindly slip forward through black water. From past experience we know there’s a delay while data is processed, so my lovely helms-lady only occasionally engaged the gears to creep Banyandah forward at less than walking pace. Meanwhile shallow alarms start ringing and with an edge in her voice she calls out that we now have “just six inches under our keel.” I tensed, dreading the touch of bottom, hoping not to ground on a sandbank exposed at 43° south.

Never in any real danger, we scraped over that skinny bit, smiling when we heard the alarm stop ringing then enjoyed two feet clearance throughout the remaining half mile to the river mouth, where next to a natural rock training wall, the depth suddenly plunged to double our depth. Jude then handed me the helm and straightaway I began zigzagging across the river sounding its narrow width, mapping an area to anchor. In doing this I ran us aground, only lightly, but then complicated our situation by running Miss “B” side-on to the bank when turning. There was a chance we’d jam our rudder backing off, but short of kedging off, in the end, going astern with power was the best choice.

Nerves jangling a bit, suddenly the riverbanks seemed a lot closer. Nevertheless, we continued to sound and found a suitable, albeit tight spot to drop our hook and proceeded to pull it in. Only to hear rumble, rumble, under easy power it grumbled across a scoured rock bottom.

Starting to doubt the wisdom of entering this river, we proceeded further upstream, past a narrow section marked by Andrew as having deep water. When it opened out again, deadheads of submerged trees were not far ahead. We tried to anchor just before them, but same story, the anchor bounced across a rock bottom.

I’m starting to feel slightly anxious. The morning is flying past and our time to paddle upstream evaporating in disappointing attempts to secure our baby. And Jude’s yammering in my ear that maybe it’d be best to exit the river and lay to anchor near the river bar. But I’m thinking I’d never relax going hours upstream knowing our vessel lay exposed to miles of fetch. In the end we decided to anchor in that slender section and run lines to both shores. Jude did the hard work, rowing ropes from both bow and stern, tying them to trees at river level. Out the stream in a deep hole close to one bank we prepared the Green Machine for our excursion; lunch, medical kit, GPS, PLB, and warm clothing and rain gear.

Paddling away was a beautiful sight of our baby floating serenely against deep forest greens reflected in the river all around her. Paddling is such fantastic exercise, with no sound of motors the glorious forest echoed with birds singing, and our difficult morning was soon forgotten.

Twenty minutes upstream the first obstacle appeared and following Andrew’s instructions we took the right-hand stream past an island, the handheld GPS now looking for the departure point to the mature Huon. South-west riverbanks are mostly abrupt with trees thick to the edge. But when the waypoint hove into view, an open muddy area gave access to the forest.

On terra firma we changed into walking boots, put on our kit bags and straightaway had to push through thick scrub. Following our GPS we occasionally spotted broken twigs or crushed clumps of razor grass, indicating others had been there, but more often the terrain required our bush skills to locate the easiest route. Through deepening bog we crossed a small stream finding the drooping green of baby Huon. Then some distance further, through a bit of thick stuff, we found the first big trees.

Research says Huon grows a millimetre in diameter each year, so the fellows next to us were probably hundreds of years old when Abel Tasman first discovered this island in the 1600s. They may not be giants, but after the Huon decimation of yesteryear, they are probably some of the largest Huon pines left on the planet.

Back again as river rats, a brisk paddle upstream rid the chill from that forest, then we enjoyed a leisurely stretch that ended when the first of many shingle rapids appeared, white water right across indicating no chance of paddling up it.

Back again as river rats, a brisk paddle upstream rid the chill from that forest, then we enjoyed a leisurely stretch that ended when the first of many shingle rapids appeared, white water right across indicating no chance of paddling up it.

Grateful I’d been a gymnast, I ‘hopped out’ very carefully, then steadied the craft so Jude could find her feet on the polished stones.

The olden day piners used to pull their punts up rapids using a long rope while another guided it. But Jude and I don’t want to risk breaking any bones and like to hang onto our kayak while pulling her up white churning water. It’s cold work, often up to our thighs in mountain water.

Once above that first waterfall, we again set off at a blistering pace, not just to get warm, but to not be sucked back down through it.

During the afternoon between rapids we enjoyed stretches of tall forest touching the river with distant mountains seen down its length while all around the sounds of Nature filled our souls with the joy of life. Sharing the work in our double kayak eased the load as we silently slipped forward clicking pictures, shooting short video clips, coming upon a platypus, a trout jumping, twin eagles soaring overhead, all without disturbing nature very much. And this reinforced our pledge to do what we can to save this wonderful planet from over development.

Till next time, we wish you beautiful sunrises to start each new day,

Jack and Jude